Translation by Julia Leverone

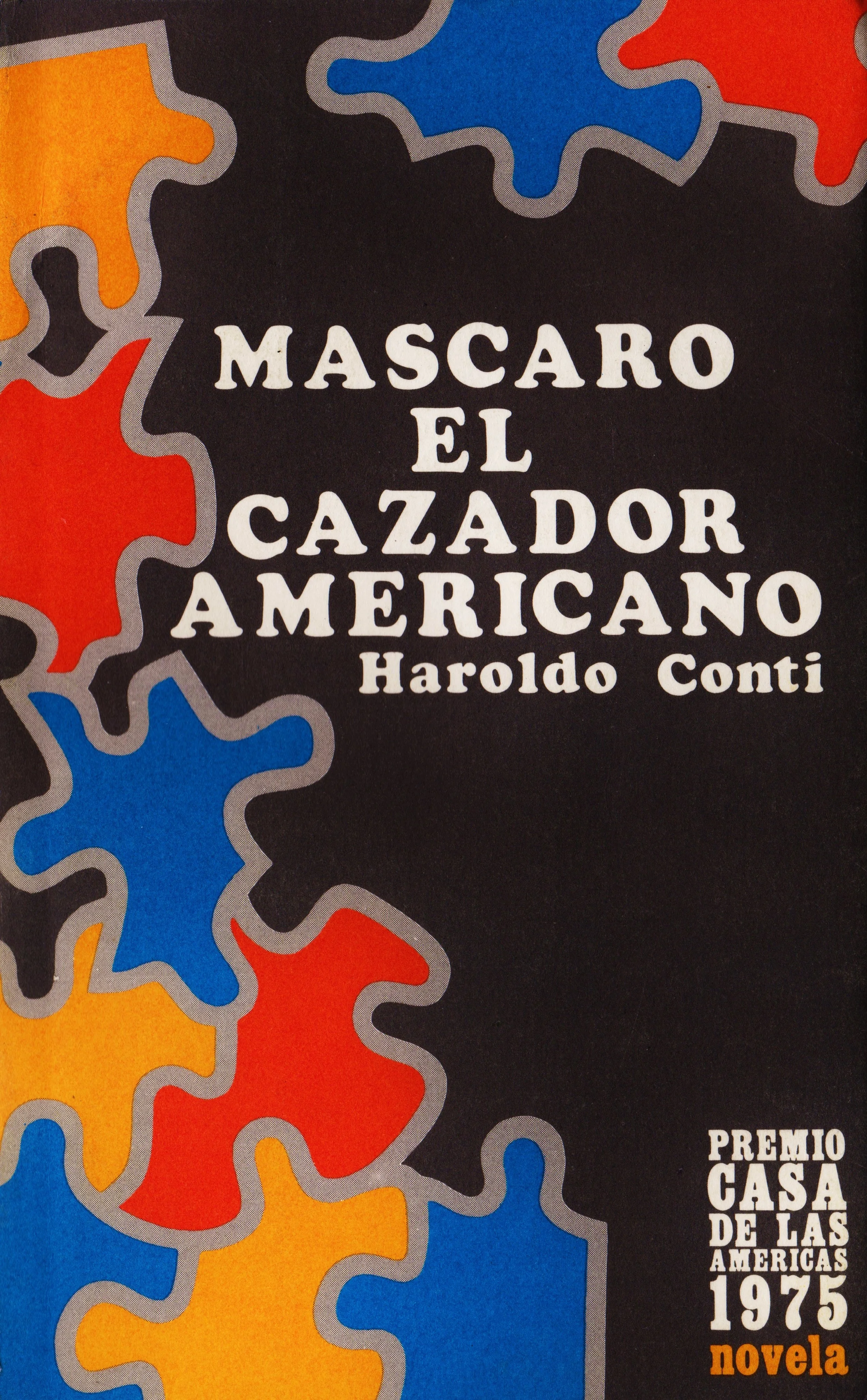

Gabriel García Márquez wrote that Haroldo Conti was one of Argentina’s greatest writers. Mascaró, the American Hunter was his final published work. The novel won the 1975 Casa de las Américas Prize, and the following year, it was designated by the military dictatorship as subversive. Conti was captured and brutally tortured, becoming one of Argentina’s disappeared at the age of fifty-one.

Mascaró is an affirmation of art’s role in self-discovery and in choosing one’s own path and personal history. It journeys in a Latin American geography, ripe with magic and story, but marked especially by the interactions of those peopling it. This excerpt depicts the protagonist Oreste’s departure from Arenales, a dune-ridden, gull-haunted, airy, dusty landscape. Mascaró, the character and mysterious rider, has not yet appeared in the narrative, nor has the brazen Prince of Patagonia, each equally integral to the novel.

Oreste’s time in Arenales and on board The Tomorrow, destined for Palmares, constitutes only a fraction of the plot, but this time is as stilled and lasting as a held breath. This moment is told of in a deeply internal perspective that Pelice’s comical bombs can hardly startle us from. The writing lingers and relishes so that we get to catch Cafuné’s wondrous and furious insertions into the commotion of the ship’s arrival; we get to experience the countless textures lying in the rooms of the hut, and feel that relics are everywhere, even within the body, within us. Oreste is a character revived from Conti’s previous novel En vida, and here, stunned but sure, we see him readying for a new life. We share in the fear and loveliness of that possibility.

Oreste's Beginning

The sun has barely climbed a few meters and already the sand burns, the light blinds. Oreste can see the igniting through his closed eyelids. His head brightens from within like a lantern.

Lirio Rocha hangs flakes of dogfish from poles for drying. The boats are gone. The sea is frazzled, tossed. Lirio heads for the third pole. The flakes all lift at the same time when a bit of wind gusts, the grains of sand crackle.

Cafuné touches that air. The day blows on.

Lirio Rocha is a leathery man, seafaring, friend of the shark. He smokes a clay pipe that currently wafts between flakes of cod. Lirio, as he pulls gradually away, looking over the lines, thins and breaks against the clarity of sea.

Oreste opens his eyes and takes account of the scene.

The musicians have gone. Remaining is the harp, alone, in the middle of the room. That’s where the night will be reconstructed.

Oreste folds the paper he has in his hand, runs the edge of his palm over it, goes out to the patio. Lucho is scraping away some sprouts. Oreste draws a pail of water from the spigot and throws it over his head. The water runs over his eyes, Lucho turns around, the dunes nearby roll over, submerge. He raises his head and feels the slipping of water over his nape, on his back. A dark bird crosses the sky. “A widowed duck,” says Lucho. “Good weather. If it passes at night, whistling: bad news.”

Oreste returns to the hut and drinks a mug of coffee. Lucho raises a few large shutters on the roof so that the heat can escape. He is a master of snatches and halyards. A stiff wind shakes the roof, Lucho secures the cords to a few screws, the hut sets out on course. The day sails.

Cafuné has stopped blowing on his flute. Oreste notices shortly afterward. He had been carrying the sound in and out, to and from his ears, he hadn’t noticed the exact moment. It is still difficult for him decide whether he can hear the flute or not. Whether or not it’s just memory. The flakes of dogfish whiten in front of the shacks, between the sea and the shacks. The statue of the Christ on the hill has a seagull on its head.

Oreste, with the paper in his hand, asks Lucho where he can find an envelope. Lucho looks at him emptily, not remembering, for a moment, what an envelope is. Oreste shakes the paper and traces the air with two fingers. Lucho goes through a few boxes. Shelves. A book with black covers that open and close like shutters and that holds long, jagged stories in mad handwriting, receipts, devotions, spells and counter-spells, a prayer to San Son, births, marriages, demises, three cures for shingles, involved and authentic supplications to Santa Lucía (eyes), San Juan (head), Santa Rita (incurable illnesses), San Vicente and San Roque (plague and leprosy), San Luis (nose), a rogation to San Cono del Obispo de Melo, and the formula for garlic balm. A packet with newspaper cutouts. A satchel for horseback riding. A wicker basket. Finally Lucho holds up an envelope.

Oreste asks if there’s a way to mail a letter. It seems that things get to Arenales but don’t leave, there is no retracing. He vaguely remembers months passing on the way out. Or years? He remembers a small, cross-eyed town, a marshy region, salt lakes, wastelands, straying paths and, in another life, a piece of road, a red truck, one final man saluting him from its cabin.

“The cod truck. It leaves from here in a month. It isn’t certain….”

Oreste smooths the paper one more time and sticks it in the envelope.

There is a row of gulls on each arm of the Christ. Lirio Rocha has finished hanging the fish pieces. For the rest of the day he’ll smoke the clay pipe, leaning back against the wall of the shack. He’ll change walls as the sun moves. When it starts to fall, he’ll bring in the fish.

Oreste takes out a piece of pencil, wets the tip, and writes with rounded letters: Margarita. Lucho narrows his eyes and examines the envelope at an arm’s distance.

“It’s missing an address. Or am I seeing wrong?”

Oreste agrees. Once a year Lucho writes to the Naval Supply Store of Palmares and a few months later receives a catalogue and an almanac. Lucho is an educated man, with interests in other worlds.

Oreste writes an address. Lucho clears a space for the envelope on a shelf, between two bottles. It’s an occasion to drink a cup of wine.

The drinkware knocks. The shutters slam. Pila shouts from somewhere. Lucho suspends the cup. A certain commotion occurs. There is a slackening of air, raspings and hisses, voices that fizz, collide. The gulls lift in flight from the arms of the Christ. Lirio Rocha cuts, smoking, out from the shadows of the shack. Something has changed.

Here comes Cafuné! He descends a mound, blazing, kicking up sand, two wheels crazy with sand, Cafuné suspended in the middle, flapping his hat, pumping his knees without looking, all flight. A horde of kids follow in his path kicking the sand, launching shells.

“The Tomorrow,” announces Lucho.

Oreste scans the sea with his eyes. Only flashes from the waves.

“No more than an hour. It has to mount the cape.”

Machuco exits the door of a ranch half asleep and begins to blow on his tuba. Cafuné pedals in circles in front of the hut. People gather. Bimbo hoists a flag at the very end of the dock, Prefecto dresses himself for the occasion.

Oreste has remained standing in the door of the hut. A body without weight. This is the day. It had been planned like this. When he lifts the cup he doesn’t realize it, but The Tomorrow is already about to turn the cape and Cafuné now clambering up the other side of the dune, the event advancing, has spotted the ship, is already enclosed within the new.

The boat appears slightly beneath the horizon. The shine on the water erases it for moments.

Pelice, who always dresses in black and isn’t seen other than on solemn occasions, appears donning a broad, grease-stained panama hat and directs himself toward the dock with a box of bombs. Pelice is a rocketeer and powderman of the Rossignon school, though for bombs he adapts the loads and proportions of Browne. His specialties are Pyrrhic pieces and glorias, Fixed Suns. Some time later Prefecto follows. Cafuné is left alone, riding around and around, Cafuné centaur. The children run behind Pelice. The people come behind Prefecto who has adorned himself with distinctive fabrics, ornamental clothing: an oilcloth hat with a gold button, a jacket with epaulettes and braids of gold thread, pants with red stripes, and some low-heeled boots, recently shined. The hat has a broken visor; the jacket, a few popped buttons and a hook for a pin at the neck, various stains, and a cigarette burn that goes clear through; the pants, a huge visible seam in the rear and a patch on both the knees; the boots, shabby like a traveler’s suitcase, are split at the toes. Nevertheless, altogether impressive.

There is a disturbance. The point of the cape stretches, separates, a tremendous jet of steam appears above the horizon and it veers abruptly toward them: The Tomorrow.

Pelice lets fly an eight-inch bomb. The reverberation shakes the hut. The Tomorrow responds with a few whistles that stammer with the wind. The jets of vapor pour like escaping sheep from one side, then the middle.

The Ballad of Arenales comes down the road behind Machuco who blows and puffs on the tuba, discordant, lowing. Cafuné leaps, brandishes a rattle. Miranda comes separately. He walks straight, gently, enduring the racket, scraping on his violin.

The Tomorrow climbs the swell of the waves, vomits steam like a factory, forces its engine, moves toward its true form, gives increasing glimpses.

Oreste remains immobile in the door of the hut. He notes the lightness of his body, his feet dance inside his shoes, he feels already gone, premature nostalgia hollows him.

The Tomorrow swerves powerfully and makes for the dock. Closer, it gains detail. The steam is slighter and the chimney visibly dirty. The hull towers like a colossus and swoops down with each lurch until there materializes at the gunwale a devout mast serving as a Samson post, a makeshift canopy, and a chewed prow. The ship bears a short prop and a figurehead, still indecipherable, that supports the bowsprit. The sound is disproportionate to the size of the vessel. There is the hollow booming of iron, the banging of the telegraph, and a stormy voice that comes from the top of the frame. A monstrosity with rolled pants and a naked torso hurls a balled line from the bow. Noy steps on the rope with a war cry. Several men pull on it, with synchronized voices. Pelice fires off another bomb, The Tomorrow spews a hoarse, long whistle, there is the hollow booming of iron, various blasts, the chimney throws a torrent of vapor that suffocates those present, and the ship jostles the dock with a vigorous vibration. It acclaims itself.

The captain Alfonso Domínguez appears half-bodied through a window and raises his fist. The Ballad lifts into a charanga, something equestrian. The flute and accordion take the part of the discourse. The snare and a one-sided drum that a young man with a stick beats set the intensity. The violin and guitar improvise embellishments, little ways of filling in. The tuba stresses the atmosphere with tidied ostentations, following the flips of Cafuné’s hand that keeps time with a baton. Missing is the blind harpist.

The people stir, part, the captain Alfonso Domínguez appears in the center, drawing the snare, and they all follow him in a mass in the direction of the hut.

Oreste sees him grow in the cavity of his eyes. The captain advances, rambling with grandeur. He projects his speech one mile to each side, to waves and to peaks. Even closer, he takes on a textual shape. He is a bulging man. He begins at the face, absolutely present, dark and shining like a cetacean. He floods in from there, prima facie, all Captain. He has eyes that are surprised, laden, that look to the interior. He moves his hands sympathetically, as far as he shows, and although they are not the hands of a priest, neither are they hard and smooth like tools. Overall, there is self-assurance, ease, and a certain measured brutality. He wears a sailor’s cap with flaps at the back of the neck. A threadbare overcoat, short pants, rubber boots to keep out the sand. Beneath the overcoat he’s dressed in leather. This is the man who will take Oreste to Palmares or who will plunge him into the middle of the sea.

Oreste moves aside and the captain Alfonso Domínguez penetrates into the hut with his arms high, surrounded by the mob of idiots that jams at the doorway. Behind come the others, The Ballad, Miranda. Lucho waves to him furiously. The Captain embraces Pila. The hut overflows.

The Captain sits in the middle of the room, near the harp, in front of a small table that he wipes with his sleeve and adjusts with his legs. Lucho serves him a tall glass of gin with well water and a squirt of lemon. Pieces of smoked bonito, cold fillets of hake, and mussels in oil.

The captain Alfonso Domínguez reports on places, people, happenings. He brings a letter from the Naval Supply Store. Everyone observes with reverence first the envelope and next Lucho. The Captain tells about a few squalls, a breakdown, accounts for certain lights or celestial fires that he saw in the night as far as Cape Sacramento, he serves himself another glass, and, by request, relates his adventures when shifted by a storm he navigated by heaving to with the Basque Pantoja one hundred eighty miles from the estuaries of Castillo and in full darkness charged one of those surging and uncertain crags that don’t appear on the maps and in that way practically discovered or at least confirmed the island of Las Cañas, which isn’t one as is presumed, but multiple islands that surround one large island, a country. There wasn’t anything left of the Pantoja except the boiler. The rest of that fucking night, so he says, he was in the water and when with the light of day he made land he met the tartans, who are very strange to run into because they never sit. These people pass the days in war and nights in celebration and dancing, which is when they drink a great quantity of the juice of the cactus, sweet and the deep color of arrope. At first they treated him badly and later they named him a physicist, which is when he struck up a friendship with the chief Gambaldo.

Oreste drinks a cup of wine in his corner by the window, and though off to the side, he hears the captain Alfonso Domínguez who, accustomed to asserting himself amid the banging around and outbursts of the old Vickers boiler, speaks at a roar.

Two men approach from the dock. The first, with a face covered in soot, is the engineer Andrés Skavak, a veritable skeleton covered only by skin. He comes on foot, naked and almost transparent from the belt upward. The second is the cook, Nuño. He walks behind Andrés with a distracted air, despite taking care to steal his steps.

The water has receded a half a block. Over the exposed dark belt of sand the shells of mussels and snails shine. Oreste sometimes keeps his pockets full of detritus, crab claws, polished stones, and those beans they call good luck. The mast of The Tomorrow has dropped to almost touching the dock that itself seems longer and taller; exposed are its lower footbridge, the rotting posts encrusted with mussels.

Andrés and Nuño enter. Andrés bends to slip around the doorframe. He gives a wave with one bone held high and takes a cup of wine at the counter. Nuño drinks a sangria with slices of lemon and a lot of honey. Andrés extricates a pack of Tuscan cigars, a biscuit, and a canteen sausage. Nuño speaks in an aside with the blind harpist. He has manners.

The captain Alfonso Domínguez tells of the frightening wave of ‘59 which had been announced five days earlier by the flight and screams of a great quantity of ibises and on which he rode with the Pantoja into the port of La Pedrera going as far as the Municipal House and snagging on the tower of the church of San Roque and how he rescued the saint with a treble hook that the parish priest had blessed from the top of the belltower.

The Captain’s gaze crosses with Oreste’s. There is another captain hiding in the shadows of those eyes.

Oreste finishes his cup. In a few hours the water will rise and The Tomorrow will set sail from Arenales because it has time-sensitive cargo. A group of fishermen are transporting bundles of cod, a few bags of shark fin, six barrels of smoked bonito, and a dozen boxes of salted prawns. Oreste calculates that by the end of the journey they will all smell of canned fish. The harpist begins to play a light waltz. The cook Nuño follows him with attention, imitates with his head the paths and turns of the music, is transported. His is a flying soul, a substance ut supra, set in verse.

Oreste crosses out of the room, and the noise of voices and strings becomes dampened behind the panels. The sound of the sea returns, the cawing of the gulls, the buzz of the body. He pushes a board aside and descends into the den where he lived all this time between miles and knots. There is a bed of wood with a horsehair mattress, a packing crate, up high, with a kerosene lantern on top, a piece of mirror mounted with two pins, a few nails for hanging clothes and his seaman’s bag. The window in the wall opens upward. It’s propped with a stick and barricaded with wire. Oreste feels at ease in this wooden carapace, most of all in the morning when he raises the window and sees the same sand landscape, and at night when he hears all that noise through the panels and lying on the bed and just closing his eyes is transported from one end of the house to the other.

The window is open. The sand extends as far as the eye can see. The wind tosses its surface. In a while the entire ground shifts, the dunes erase on one side. The sea enters from a slant, to the right. It’s a rim of foam, glints, and mists that hammocks in the eyes and, for moments, stills. Oreste closes his eyes and sees it, paler, as if it ran through him back and forth and he were only an idea and then eventually nothing. Sand, sea, and sky merge at a distance. If you raise yourself up on the tip of your toes the world stretches a few meters.

The racket from the hut has continued growing without raucousness, seeps through the walls, gets into all the holes and cracks, emerges from the air itself. The captain Alfonso Domínguez speaks at this minute of the time they went with Father Crespillo and the Commissioned Prefect of the Coloradas to the tremendous marshes of Abra Vieja in search of the glowing cocuyo or ember bird and how after all kinds of danger, among them the old woman Julia Lafranconi who shot at them with a sawed-off shotgun, the woman who lives there and was declared dead a thousand times and was even thought to be invented, they found it above a foresty swathe of ferns and captured it alive right then and there by using a charm that Father Crespillo had composed with precise measurements and proportions, as was demonstrated in fraganti, and so they extracted from the insect that stone or mirror without harm, but on their return the boat capsized and it was lost in the chop of the water and from the shock Father Crespillo forgot his charm completely.

At another point a stricken voice climbs in flight and sings the pained copla of La Madreselva. The harp surrounds the song with stirring kindnesses, scales and arpeggios that intertwine with the phrases, a light tremoring in the air.

Oreste collects his garments and whatever else there is scattered across the room. Apart from the clothes he has on, it isn’t much. A hunting knife, some dulled boots, a pipe with a cracked pot that he found on the beach, a disbound book of the adventures of The Two Scamps, a lantern, a paintbrush, a razor blade, a pocketwatch that lacks the little minute hand, an aluminum kettle, a flask, a sewing box, a bottle of rubbing oil, a leather hat, a deck of Spanish cards, a notebook, a caburé feather inside a pillbox, a few shells, and a dry compass. He does not possess anything else on this earth. He puts it all in his bag, without haste, revisiting the origins of each object, but the memories mix, they disrupt. In the end they only float in his head as loose images, figures. He cinches the neck of the bag with care, lifts it, and loads it onto his shoulder.

With this, he gives one more glance over the room and stays for a time standing near the door with a stranger’s air. This is Oreste Antonelli, or plainly, Oreste. A vagabond, almost an object himself. His hair has grown behind his neck to his shoulders. He has a taut and dark face, awestruck eyes, a patchy and disorderly beard. It’s been months since he’s worn the seaman’s cape with the hood into which he usually throws whatever he finds along his way. Underneath he wears nothing but a shirt. Even the canvas pants, tight and faded, are the same as those he had set out with. His boots are weak and broken, the water enters through his soles, but he has developed an affection for them because they carry and even choose for him. When Oreste pictures himself walking it’s wearing them and when he removes them he feels he has simply ceased to be Oreste. It’s been a while since he has taken off his socks and underwear, societal items. The last part of him is his seaman’s bag and when, like now, he puts it on his shoulder, time closes and life turns.

The door opens. There is Pila standing before Oreste, her eyes wet, her skin burning, tremble and rage of the soul, present and absent in the transience of the moment, wholly an image for memory.

Oreste moves forward a step, which is to say, he begins to leave. Already on his way, without offloading the bag, he brings her toward him and kisses her without the weight of flesh, in absence.

A shot fires, distant. It’s the signal from Prefecto. The water has risen.

The people have already gone in a flock behind the always-Captain. Lucho has stayed back, alone by the bar, in the dark. The hut seems now larger and cooler and the air that enters by pushing in through the roof rustles the straw. Oreste will remember it this way. Only a few times has he known it like that, empty and shaken out like a shell. And other times, at night, when it was not a room, but a frame of light with the angel in the middle, president, and The Ballad of Arenales wavering on the air.

The group moves off in the direction of the dock under the intense light of the afternoon that cuts outlines severely. Oreste sees them through the hole of the door, one very large eye, they in the light, walking toward the dock, climbing over the line of foam and then the whole sea and then a part of the sky, simply an evener blue, and he barely encaved in the hut, as if everything he saw were by the shadow of his hand. He sees the hat of the Captain rising and sinking and the little cloud of gulls wheeling over their heads, a white fleece, a dark stain depending on how they tilt.

The Tomorrow towers over the dock, the mast scrapes the sky gently. The prow tips up ignorantly so that the figurehead flies into full view. Prefecto and Pelice are already there, within their roles.

“They’ll have a nice time,” says Lucho now from the door, without turning. That time, belonging to those who are leaving, is no longer the time of others.

Oreste, before going, throws an arm around Lucho.

“We’ll see each other again,” says Oreste without conviction, and repeats it loudly like an augury or formula and then asks himself if it really came from him.

Lucho nods his head, confusing Oreste even more. Lucho says:

“There are ways.”

And as he says it he passes Oreste a little bottle with a wax stopper.

“It’s a medicine for travelers, above all for those on foot. You rub it in. It’s made with marshmallow, ox fat, rock salt, and burning alcohol, but everything depends on the alchemy of it, which is the secret. It is especially good for stiffness, boils, worms, breaks, dislocations, joint pain, sadness, and every road affliction. Put it on in the early morning.”

Oreste takes the bottle and holds it against the light. A white dust detaches from the bottom, coils in the center, and then sinks. It seems a thing alive. He slips the bottle into his right pocket, in a show of respect.

They hear voices rising, some varied shouts. The mast of The Tomorrow tips with violence. The captain Alfonso Domínguez has just leapt to the deck.

Oreste juts his head forward and submerges into the light. He walks for a stretch carefully, transparent as a bottle. Children run toward him crying out, they jump and shout in a circle, scare the gulls that shriek over his head. Unsettled air of departure. Oreste gives a forced smile. He crosses in strides the burning sand of the mounds to which his feet have become accustomed, carried by the fine friction of the grains that break down underneath his soles and by short flights of dust, then the hard sand of the beach that dampens his skin through the holes in his shoes, sheer body, a faintly familiar figure, he, Oreste, rolling, rolling, like a pebble inside a pumpkin.

El comienzo de Oreste

El sol apenas había remontado unos metros y ya ardía la arena, cegaba la luz. Oreste ve la claridad que se inflama a través de los párpados cerrados. Su cabeza se ilumina por dentro como una lámpara.

Lirio Rocha cuelga de las varas las hojas de cazón. La Malaque ha desaparecido con la marea. Los botes se fueron. El mar está cresposo, removido. Lirio, a medida que se aleja recorriendo la vara, se afina y se parte contra la claridad del mar.

Oreste abre los ojos y constata.

Lirio va por la tercera vara. Las hojas se viran a un mismo tiempo cuando sopla un poco de viento, los granos de sal chisporrotean. Lirio Rocha es de la Punta del Diablo. Baja a Arenales para la zafra. Hombre correoso, marítimo, compadre de tiburón, fuma una pipa de barro que ahora humea entre las hojas de bacalao.

Cafuné toca ese aire. Sopla el día.

Los músicos se han ido. Queda el arpa, sola, en medio del salón. Por ahí se reconstruye la noche.

Oreste dobla el papel, lo repasa con el filo de la mano, sale al patio. El Lucho está raspando unas brótolas. Oreste jala un balde de agua de la cachimba y se lo echa sobre la cabeza. El agua chorrea sobre sus ojos. El Lucho se revira, los médanos se doblan, se sumergen. Levanta la cabeza y siente el resbalón del agua sobre la nuca, en la espalda. Un ave negra cruza el cielo en dirección a Aguas Dulces. “Pato viuda”, dice el Lucho. “Buen tiempo. Si pasa de noche silbando: malas noticias.”

Oreste vuelve al salón y bebe un jarro de café. El Lucho levanta unos postigones en el techo para que escape el calor. Es un ingenio de pastecas y drizas. Un ventarrón sacude el techo, el Lucho amarra las cuerdas a unas cabillas, el salón emprende una singladura. Se navega el día.

Cafuné ha dejado de soplar. Oreste lo nota algo después. Trae y lleva un ruido en la oreja, de manera que no se repara en el momento. Aun es difícil decidir si suena o no. Y cuando suena si no es memoria. Las hojas de cazón blanquean frente a los cobertizos, entre el mar y los cobertizos. El Cristo tiene una gaviota sobre la cabeza.

Oreste, con el papel en la mano, pregunta al Lucho dónde puede conseguir un sobre. El Lucho lo mira, vacío, sin recordar de momento qué es un sobre. Oreste agita el papel y enmarca el aire con dos dedos. El Lucho revuelve unas cajas. Los estantes. Un libro de tapas negras que se abren y cierran como postigos y en el cual lleva largas y torcidas cuentas con rayada escritura, recetas, devociones, conjuros y contramaleficios, la oración a San Son, nacimientos, casamientos y finales, tres ensalmos para tratar la culebrilla, las embrolladas y auténticas rogativas a Santa Lucía (ojos), San Juan (cabeza), Santa Rita (dolencias incurables), Santos Vicente y Roque (pestes y lepra), San Luis (nariz), la súplica a San Cono del Obispo de Melo y la vera fórmula de la tintura de ajo. Un paquete con recortes de diarios. Un morral de caballería. Una cesta de mimbre. Al fin enarbola un sobre.

Oreste pregunta si hay forma de despachar una carta. En apariencia se llega a Arenales pero no se vuelve, no se desanda. Recuerda vagamente meses de marcha. ¿O años? Recuerda una aldea de bisojos, una comarca de pantanos, los tremendos Campos de Talampaya, páramos, salinas, extravíos y, en otra vida, un trozo de camino, un camión rojo, el último hombre que lo saluda desde la cabina.

—El furgón del bacalao. De aquí en un mes. No hay seguridad…

Oreste alisa otro poco el papel y lo mete en el sobre.

Hay una hilera de gaviotas en cada brazo del Cristo. Lirio Rocha ha terminado de colgar las hojas. El resto del día fuma la pipa de barro, recostado contra la pared del cobertizo. Cambia de pared según se mueve el sol. Cuando comienza a caer, entra las hojas.

Oreste extrae el trozo de lápiz, moja la punta y escribe con letras redondas: Margarita.

El Lucho entrecierra los ojos y examina el sobre a la distancia del brazo.

—Falta la dirección. ¿O veo mal?

Oreste concuerda. Una vez al año el Lucho escribe al Almacén de Efectos Navales de Palmares y recibe algunos meses después un catálogo y un almanaque, y al señor Adolfo Martí, físico y herbolario de Sacramento. El Lucho es hombre de instrucción, le preocupan los mundos.

Oreste escribe una dirección. El Lucho aloja el sobre en un estante, entre dos botellas. Es ocasión para beber un jarro de vino.

Golpean los jarros. Los postigones se agitan. La Pila grita por algún lado. El Lucho suspende el jarro. Ocurre cierta algarabía. Hay un quebranto del aire, raspados y chifles, voces que burbujean, entrechocan. Las gaviotas levantan vuelo de los brazos del Cristo. Lirio Rocha se raja humeante de las sombras del cobertizo. Suceso.

¡Ahí viene Cafuné! Baja una loma a los pedos arrastrando arena, dos ruedas locas de arena, Cafuné suspendido en el medio sobre una raya, agitando el sonajero, hundiendo y remontando las rodillas sin mirar a nadie, todo volante. Un tropel de chicos lo sigue a la carrera pateando arena, disparando caracoles.

—El Mañana —anuncia el Lucho.

Oreste abarca el mar con los ojos. Sólo brillos.

—No más de una hora. Tiene que montar el cabo.

El Machuco sale a la puerta del rancho medio dormido y comienza a disparar el bombardino. Cafuné pedalea en círculo frente a la barraca. La gente concurre. El Bimbo iza una bandera en la punta del muelle, el Prefecto se reviste, aparece la Malaque a todo paño por detrás del faro.

Oreste ha quedado de pie en la puerta de la barraca. Cuerpo sin peso. Éste era el día. Estaba así tramado. Cuando levantó el vaso no lo sabía, pero la Malaque ya estaba por doblar el cabo y Cafuné trepaba por el otro lado del médano, adelantaba el suceso, había avistado el Mañana a la altura de Punta Almagro, él ya estaba en lo nuevo.

Aparecen los botes un poco más abajo del horizonte. El brillo del agua los borra por momentos.

El señor Pelice, que viste siempre de negro, calza un panamá alerudo y grasiento y no se lo ve más que en ocasiones de solemnidad, se encamina hacia el muelle con una caja de bombas y un mortero. El señor Pelice es cohetero y polvorista, de la escuela de Rossignon, aunque para las bombas se ajusta a las cargas y proporciones de Browne. Su especialidad son las piezas pírricas y las glorias o soles fijos. Algo después lo sigue el Prefecto. Cafuné queda solo, rodando, rodando, Cafuné centauro. Los chicos corren detrás del señor Pelice. La gente proviene con el Prefecto que luce paños distintos, ropa de ornamento: gorra de hule con botón dorado, chaqueta con caponas y trencillas de hilo de oro, pantalón con vivos de color rojo y unas botas de caña corta recién engrasadas. La gorra tiene la visera quebrada; la chaqueta, con algunos botones saltados y un alfiler de gancho a la altura del cuello, varias manchas de grasa y una matadura de cigarrillo que la traspasa, los pantalones, un costurón en los fondos y un remiendo en las rodillas; las botas, ajadas como la maleta de un viajante, están partidas en la capellada. Sin embargo, el conjunto es de impresión.

Hay revuelo. Obsérvese. La punta del cabo se estira, se separa, un chorro de humo mayúsculo se eleva sobre el horizonte y tuerce bruscamente hacia Palmares: el Mañana.

El señor Pelice suelta una bomba de ocho pulgadas. El retumbo sacude la barraca. El Mañana responde con unas pitadas que se atoran con el viento. Los chorritos de vapor escapan como corderos por un costado de la chimenea, en la mitad.

La Malaque arría las velas y echa el ancla de apuro, una galápago herrumbrosa. Desde la barraca se siente el repicar de la cadena que resbala por el escobén. Los botes vienen detrás, de competencia. Las palas brillan en el aire, se oscurecen, se hunden, todas a un mismo tiempo. Revueltos hoyos brotan consecuentes a popa. El timonel ordena, cuenta. Los hombres gritan acordes a cada pechazo. Los botes encallan con el último impulso. ¡Ehhh! Bombas y pitadas trastocan el aire.

La Trova de Arenales sobrevive a la carrera detrás de Machuco, que sopla y resopla el bombardino, discordante, mugidor. Cafuné salta, rebate el sonajero. Miranda viene apartado. Camina derecho a los pasitos, apuntando a los ruidos, raspando el violín.

El Mañana remonta la hinchazón de las olas, vomita humo como una fábrica, fuerza la máquina, navega pertinente hacia su forma exacta, adelantando esbozos. Oreste sigue inmóvil en la puerta de la barraca. Nota el cuerpo liviano, los pies le bailan dentro de los zapatos, se siente ya ido, lo ahueca la nostalgia. Todavía es hombre de tristezas.

El Mañana vira con esfuerzo y enfila hacia el muelle. Más cerca se define. Es un vaporcito con una chimenea mugrosa, una carroza que sobresale como un ropero y se abate a cada bandazo hasta asomar por la borda, un palo piolo que sirve para mástil de carga, una toldilla somera y una proa abollada. Porta un botalón corto y un mascarón todavía indescifrable que lo sostiene con la cabeza. El ruido no guarda proporción con el tamaño de aquel patacho. Se siente un hueco tronar de fierros, el traqueteo del telégrafo y una voz de borrascas que sale de lo alto de la carroza. Un esperpento con los pantalones arremangados y el torso desnudo arroja desde la proa un cabo de bola. El Noy pisa el cabo con un grito de guerra. Varios hombres halan el calabrote, con voces acompasadas. El señor Pelice dispara otra bomba, el Mañana escupe una ronca y larga pitada, hay un tumulto de fierros, soplidos varios, la chimenea lanza un torrente de humo que sofoca a los presentes y el barco sacude el muelle con una recia estropada. Se aclama.

El capitán Alfonso Domínguez asoma medio cuerpo por una ventana y saluda con el puño. La trova arremete con una charanga, algo ecuestre. La flauta y el acordeón llevan la parte del discurso. El redoblante y un tambor de un solo parche que bate un muchacho con un garrotito exponen lo recio del asunto. El violín y la guitarra improvisan adornos, maneritas de relleno. El bombardino remacha los aires con estruendos ordenados siguiendo los volteos de la mano de Cafuné, que marca el compás con una vara. Falta el arpero ciego.

La gente se remueve, se aparta, el capitán Alfonso Domínguez sobreviene en el medio, transita redoblante, lo siguen de algarada en dirección a la barraca.

Oreste lo ve crecer en la cavidad de sus ojos. Avanza parloteando con grandes maneras. Habla de una milla a otra, a olas y peñascos. Más cerca se configura textual. Es hombre de bulto. Empieza por la cara, absolutamente presente, oscura y lustrosa como la de un cetáceo. Se infunde por allí, prima facie, todo Capitán. Tiene ojos de asombro, cargados, que miran en lo interior. Mueve las manos con ajuste, según expone, y si bien no son las manos de un canónigo, tampoco son de esas duras y melladas como una herramienta. En conjunto, hay desenfado, garbo y cierta mesurada brutalidad. Lleva una gorra marinera con la orla que ondea por detrás de la nuca. Un gabán raído, un pantalón corto, botas de goma que pasean la arena. Debajo del gabán está en cueros. Ése es el hombre que lo llevará a Palmares o lo hundirá en medio del mar.

Oreste se aparta y el capitán Alfonso Domínguez penetra en la barraca con los brazos en alto rodeado por la turba de pendejos que se atasca en la puerta. Detrás vienen los otros, la Trova, Miranda. El Lucho saluda con arrebato. El Capitán abraza a la Pila. La barraca se colma.

El Capitán se sienta en medio del cuarto, cerca del arpa, frente a una mesita que limpia con la manga y se acomoda entre las piernas. El Lucho le sirve un vaso alto de ginebra con agua de pozo y un chorro de limón. Trozos de bonito ahumado, milanesas frías de brótola y mejillones en aceite.

El capitán Alfonso Domínguez informa sobre lugares, personas y sucesos. Trae una carta del Almacén de Efectos Navales. Todos observan con reverencia primero al sobre y después al Lucho, letrado. El Capitán cuenta algunas borrascas, una avería, da cuenta de ciertas luces o fuegos celestes que vio en la noche a la altura del Cabo Sacramento, se sirve otra copa y, a pedido, relata sus aventuras cuando corrido por una tormenta navegaba a la capa con el Vasco Pantoja ciento ochenta millas frente a los esteros de Castillo y en plena noche embistió uno de esos peñascos surgentes o errátiles que no figuran en las cartas y fue así como prácticamente descubrió o por lo menos confirmó la isla de Las Cañas, que no es una, como se presume, sino varias que rodean una grande, un país. Del Pantoja no quedó más que la caldera. El resto de esa puta noche estuvo en el agua, y cuando con la luz del día salió a tierra, vino a dar con los indios tartanes, que son muy raros de topar porque nunca están de asiento. Estos indios pasan el día en guerras y las noches en fiestas y areitos, que es cuando beben gran cantidad del zumo de las tunas, dulce y de color de arrope. Primero lo maltrataron y luego lo nombraron físico, que fue cuando trabó amistad con el cacique Gambado.

Oreste bebe una jarra de vino en su rincón, junto a la ventana, y aunque de un lado oye el ancho resuello del mar que nunca declina, por el otro escucha al capitán Alfonso Domínguez que, acostumbrado a imponerse a los golpes y arrebatos de la vieja caldera Vickers, habla a los estampidos.

Dos hombres se aproximan desde el muelle. El primero, con la cara cubierta de tizne, es el maquinista Andrés Skavak, una notable osamenta con la sola piel encima. Viene en patas, desnudo y casi transparente de la cintura para arriba. El segundo es el cocinero Nuño. Camina detrás del Andrés con aire distraído, aunque poniendo cuidado en saltear sus pisadas.

El agua ha retrocedido una media cuadra. Sobre la faja oscura de la arena que queda al descubierto brillan las cáscaras de almejas y caracoles. Oreste trae a veces los bolsillos repletos de caparazones, pinzas de cangrejos, piedras pulidas y esas habas que llaman de buena suerte. El palo del Mañana ha descendido casi a ras del muelle, que a su vez parece más largo y más alto, muestra la pasarela inferior, los postes podridos e incrustados de mejillones.

Entran el Andrés y el Nuño. El Andrés se inclina para transponer la puerta. Saluda con un hueso en alto y bebe una jarra de vino en el mostrador. El Nuño bebe una sangría con rodajas de limón y un chorro de miel. El Andrés señala un paquete de toscanos, una galleta de campo y una longaniza cantinera. El Nuño habla en un aparte con el arpero ciego. Tiene modales.

El capitán Alfonso Domínguez relata la espantosa creciente del 59, que fue anunciada cinco días antes por el vuelo y los gritos de gran cantidad de bandurrias y en la cual entró con el Pantoja hasta la Casa Municipal del puerto de la Pedrera y amarró a la torre de la iglesia de San Roque y cómo rescató al santo con un grampín que bendijo el párroco desde lo alto del campanario.

La mirada del Capitán se cruza con la de Oreste. Hay otro capitán parapetado en las sombras de aquellos ojos.

Oreste apura el jarro. En un par de horas levantará el agua y el Mañana zarpará de Arenales porque lleva carga de apuro. Un grupo de pescadores transporta fardos de bacalao, algunas bolsas de aleta de tiburón, seis barriles de bonito ahumado y una docena de cajas de camarón salado. Oreste calcula que al término del viaje olerán a conserva de pescado. El arpero ciego comienza a tocar un valseadito. El cocinero Nuño lo sigue con atención, acompasa con la cabeza las maneras y giros de la música, se transporta. Es alma volátil, de sustancia ut supra, en verso.

Oreste atraviesa el salón, y el ruido de voces y cuerdas se opaca detrás de las maderas. Reviene el ruido del mar, el graznido de las gaviotas, los rumores del cuero. Empuja una tabla y penetra en el socucho donde habitó todo este tiempo en millas y nudos. Hay una cama de madera con un colchón de crin, un cajón de embalar, a lo alto, con una lámpara de querosén encima, un trozo de espejo sujeto con dos tachuelas, algunos clavos para colgar la ropa y el bolso marinero. La ventana en la pared abre para arriba. Se sostiene con un palo y se tranca con un alambre. Oreste se siente a gusto en ese caparazón de madera, sobre todo por la mañana cuando iza la ventana y ve el mismo paisaje de arena y por la noche cuando oye todo ese ruido a través de las maderas y él está echado en la cama y con sólo cerrar los ojos se transporta de un lado a otro de la casa.

La ventana está abierta. La arena se extiende hasta donde alcanza la vista. El viento remueve la superficie. Al rato el suelo entero se desliza, los médanos se borran de un lado. El mar penetra oblicuamente a la derecha. Es un borde de espumas, brillos y vapores, que se hamaca en los ojos y por momentos se fija. Oreste cierra los ojos y lo ve apenas más pálido, como si lo traspasara de lado a lado y él apenas fuera una idea y después nada. Arena, mar y cielo se juntan a lo lejos, un poco antes del Aldebarán que Oreste adelanta con su memoria y casi lo ve. Si uno se suspende en la punta de los pies el mundo se alarga unos metros.

El barullo del salón ha ido creciendo sin estridencias, traspasa las maderas, se mete en todos los huecos y hendiduras, proviene del aire. El capitán Alfonso Domínguez habla en este momento de la vez que fueron con el padre Crespillo y el Prefecto comisionado de Las Coloradas hasta los tremendos pantanos de Abra Vieja en busca del carbunclo o pájaro brasa y cómo al cabo de toda clase de peligros, entre ellos la vieja Julia Lafranconi que les disparó con una escopeta recortada, la vieja que vive allí y decretaron mil veces por muerta y aun como invento, dieron con él sobre un helecho arborescente y lo cazaron vivo y sin daño por medio de un ensalmo que había compuesto el padre Crespillo con las medidas y proporciones exactas, como se demostró in fraganti, y le extrajeron allí mismo la piedra o espejo sin violencias corporales, pero de regreso volcó el bote y se perdió en el movido del agua y con el susto el padre Crespillo olvidó el ensalmo.

En otra punta una voz enlutada remonta vuelo y canta la dolida copla de La Madreselva. El arpa envuelve el canto con removidas finezas, escalas y arpegios que entrecruzan las frases, temblorcito del aire. Oreste recoge sus prendas y cuanta cosa hay desparramada por el cuarto. Además de la ropa que lleva puesta, no son muchas. Un cuchillo de monte, unas botas descoloridas, una pipa con la cazuela rajada que halló en la playa, un libro descuadernado con las aventuras de Los dos pilletes, una linterna, una brocha, una navaja, un reloj de bolsillo al que le falta la manecilla de los minutos, una pava de aluminio, una cantimplora, un costurero, un frasco de linimento, un gorro de piel, un mazo de barajas españolas, un cuaderno, una pluma de caburé dentro de una cajita de pastillas, algunos caracoles y una brújula seca. No posee otras cosas sobre esta tierra. Mete todo en el bolso, sin apuro, repasando el origen de cada cosa, pero los recuerdos se mezclan, se trastocan. Al fin tan sólo flotan en su cabeza imágenes sueltas, figuras. Ciñe el cuello del bolso con un tiento, lo sopesa y se lo carga al hombro.

Así, con el bolso al hombro, echa una última mirada al cuarto y permanece un rato de pie cerca de la puerta con aire forastero. Éste es Oreste Antonelli, o más bien Oreste a secas. Un vagabundo, casi un objeto. El pelo le ha crecido detrás de la nuca hasta los hombros. Tiene la cara chupada y oscura, los ojos deslumbrados, una barba escasa y revuelta. Hace meses que viste el mismo capote marinero con un capucho en el que suele echar cuanta cosa encuentra en el camino. Debajo no tiene más que la camisa. También los pantalones de brin, estrechos y descoloridos, son los mismos con los que se largó al camino. Los botines están resquebrajados y rotos, el agua le entra por las suelas, pero les ha tomado cariño porque ellos lo transportan a todas partes y hasta escogen el camino. Oreste se figura que anda dentro de ellos y cuando se los quita es precisamente cuando deja de ser el Oreste a secas. Hace tiempo que ha desechado las medias y los calzoncillos, que son prendas de sociedad. El grillete del Aldebarán es cosa nueva, chisme para metafísicas, cosita de encantamiento. Por último está ese bolso marinero que cuando, como ahora, se echa al hombro, clausura un tiempo y tuerce la vida.

En esto se abre la puerta. Ahí está la Pila de pie frente a Oreste, los ojos húmedos, la piel encendida, temblor y arrebato del alma, presente y ausente en lo transeúnte del momento, entera figura para la memoria.

Oreste adelanta un paso, es decir, comienza a irse. Ya de camino, sin descolgar el bolso, la atrae con suavidad y la besa sin el peso de la carne, en ausencia.

Suena un disparo, lejos. Es el aviso del señor Prefecto. Ha subido el agua.

La gente ya se ha ido en bandada detrás del siempre Capitán. El Lucho ha quedado solo cerca de la puerta, en lo oscuro. El salón parece ahora más grande y más fresco y el aire que penetra a los empujones por el techo remueve la paja. Oreste lo recordará así. Unas veces así, vacío y sacudido como un cascarón. Otras de noche, no un cuarto, sino un recorte de luz con el ángel en el medio, presidente, y la Trova de Arenales divagando esos aires.

El grupo se aleja en dirección al muelle bajo la luz intensa de la tarde que recorta con dureza sus siluetas. Los ve por el hueco de la puerta, a través de un ojo muy grande, ellos en la luz, caminando hacia el muelle, trepando el borde de espumas y después el entero mar y después una parte del cielo, simplemente un azul más parejo, y el encuevado en el salón, como si lo viese todo a la sombra de la mano. Ve la gorra del Capitán que sube y baja y la nubecita de gaviotas que revolotean sobre las cabezas, un vellón blanco, una mancha oscura según se ladean.

El Mañana sobresale del muelle desde la línea de agua, el palo raspa el cielo suavemente. La proa se empina como un sueco, de manera que el mascarón sobrevuela el muelle. El Prefecto y el señor Pelice ya están allí, en oficios.

—Tendrán buen tiempo —dice el Lucho desde la puerta, sin volverse.

Habla del tiempo de ellos, los que se van, que ya no es el mismo.

Oreste, antes de salir, le echa un brazo. El Lucho huele a humo de laurel.

—Nos volveremos a ver —dice Oreste sin convicción, y después lo repite más fuerte, como un augurio o fórmula, y se pregunta si salió verdaderamente de él.

El Lucho asiente con la cabeza, y eso lo confunde todavía más. Dice el Lucho:

—Hay maneras.

Y al tiempo que lo dice le alarga una botellita con un tapón de lacre.

—Es una medicina para viajeros, sobre todo de a pie. Se frota. Está hecha con malvavisco, grasa de buey, sal gruesa y alcohol de quemar, pero todo depende de la mixtura, que es la secreta. Es especial para forzadas, chupos, embichamientos, quebraduras, zafaduras, pasmaduras, tristes y todo mal de camino. Se unta de madrugada.

Oreste toma la botella y la sostiene contra la luz. Una borra blanca se desprende del fondo, se enrosca en mitad del frasco y luego se sumerge. Parece algo animado. Desliza la botella en el bolsillo de la derecha, en señal de respeto.

Se oyen voces de arrebato, los varios gritos. El palo del Mañana se ladea con violencia. El capitán Alfonso Domínguez acaba de saltar a la cubierta.

Oreste echa la cabeza para adelante y se sumerge en la luz. Camina un trecho a tientas, transparente como un frasco. Los chicos corren hacia él dando voces, saltan y gritan en círculo, espantan a las gaviotas que chillan sobre su cabeza. Revuelto aire de partida. Oreste sonríe forzadamente. Atraviesa a los trancos la arena ardiente de las lomas a la cual se han acostumbrado sus pies, se transporta sobre el fino roce de los granos que se trizan debajo de las suelas y el corto vuelo del polvo y después sobre la dura arena de la playa que le humedece la piel a través de los agujeros, mero cuerpo, figura semejante, y él, Oreste, rodando, como un guijarro dentro de una calabaza.

Julia Leverone is ABD in comparative literature at Washington University in St. Louis. She has placed translations of poems by Paco Urondo in publications including The Massachusetts Review, Witness, Tupelo Quarterly, Modern Poetry in Translation, and InTranslation, where she was nominated for The Pushcart Prize. Her first chapbook of poems, Shouldering, will appear in March 2016. Julia is Editor of Sakura Review. Her website is julialeverone.com.