TRANSIENTS WELCOME

—for my grandfather

I walk down through Manhattan

from the Bronx, tracing the path

you must have taken in the hunt

for your first job in America,

some hotel on Park Avenue

you could never afford to stay in.

No money for a cab, you must

have walked the crowded city

in awe, more people on a single

street corner waiting to cross

then there were in the whole

Dominican Republic you left behind.

No money for the subway,

though maybe you considered

becoming a conductor,

despite the fear of being underground—

they must get paid well to wield

such huge machinery—

but you didn’t come here to lead

people through darkness. Or did you?

Uptown now, where your son,

my father, will enroll in City College,

the first in the family to have his degree.

Uptown, where the trains emerge

Bronx bound or bent towards Queens,

or dive right into the very ground

you walk on below Manhattan

towards Brooklyn or far off Staten Island,

where another son is still locked up

in an asylum, Uncle Kiko in the embrace

of schizophrenia. He might be in the same

room you used to visit him in, I wouldn’t know.

I don’t visit him. I keep walking

just as you must have kept walking,

eyes bouncing around like a pinball—

the bars with strange names,

clothing stores, Chinese restaurants,

a post office, a donut shop with a bold

red sign that says HOT & READY

but not HIRING, and what do you know

about donuts anyway? You must have

walked past this same bodega in Washington Heights,

contemplated stopping for smokes

but there was no money for cigarettes

yet, and besides, you’ll smoke twice as much

when your wife dies from lung cancer.

I have cousins in Washington Heights

that I would not recognize

if they were standing next to me on

this very same corner crossing

in the same direction but I keep walking

past coffee shops and food stands,

a farmers market, a pawn shop with a sign

that reads WE BUY ANYTHING

but not HIRING, and you don’t have much

to sell anyway, anything of value

already gone to pay for the plane tickets,

the first months rent, food, a new

pair of shoes that lead you past

the length of Central Park. Did the acres

of autumned trees dishearten you,

leaves breaking from stems like

drifting days? Or had the decades

already taught that spring returns with

or without us? Midtown within sight

now, how the skyscrapers must have

floored you. The Empire State,

The Chrysler. Or perhaps you were

skeptical. Rascacielo?

How could the snow not come down

if their spires were truly piercing the clouds?

Did you consider going up

to the top floor of one to see

for yourself? But there wasn’t much

time, the evening growing thin around you

as it does right now, the streetlights

coming to life, and an electric blue sign

down the block springs into view

in the window of a hotel, the words

TRANSIENTS WELCOME, and below

in red handwriting: HELP WANTED.

O CHRISTMAS TREE

With my last two dollars I buy a coffee

to warm my ungloved hands, snow falling

soundlessly onto my upturned face

beneath the shadow of an enormous

Christmas tree, a skyscraper raised

overnight in midtown New York.

I try to fathom the flatbed it came to town in

from some far-northern Paul Bunyan

forest, and remember the eighteen wheelers

full of classic Fraser Firs and woolly Douglas trees

that I had to unload by hand when I worked

at a Home Depot in North Miami.

The trees were always stacked and netted

like body bags, from smallest to largest,

making it as difficult as possible to unload,

with the menacing twelve footers

still waiting in the back after hours

of dragging and lifting, dragging and lifting.

That winter was cold enough to send

the snowbirds home, temperatures dropping

to the upper 20’s at night, and it was always cold

in those refrigerated trucks, though the sap

that oozed from the trees wasn’t quite frozen

and so it would stick to my jeans, hoodies, gloves,

and that stupid orange apron, leaving me sap-

stained from head to aching feet. This was after

I graduated college, when I was so broke

I called out sick because I couldn’t afford to put gas

in the car that week to drive up to work and threw

up from eating ramen noodles for four days straight.

Never broke enough to pick up a penny

on the street though, knowing damn well

how worthless they are, not even pure copper—

even Abe is embarrassed, casting a sideways

stare to avoid eye contact. Those were the days

when I’d come home broken and stare

at my English degree hanging on the wall

like a crucifix that never answered a prayer.

I couldn’t even afford a Christmas tree,

not even one of those shitty plastic tabletop ones,

and hated everyone who shopped at Home Depot

for theirs, having to cut the netting and twirl

tree after tree, only for them to say,

again and again: Eh, I don’t know.

How about that big one in the back?

and I hated them even more, hoped the tree

they picked was full of spiders, even dead ones,

which often turned up in the frozen trucks

with their eight glazed eyes multiplying

the darkness, legs like dried pine needles.

Or maybe a stiff robin would drop down

on their gifts as their children hung lights

and angels from the branches, its beak

parted in yellowed silence. I always imagined

those creatures that turned up in the trailers

as sad, strange little immigrants fleeing

their homeland, smuggling themselves

in the trees, the trucks, their homes

destroyed but deciding to stay in them,

seeing the semi’s license plate and dreaming

of Florida, that legendary place only mentioned

in the chatter of migratory birds, though I was

the only living thing ever inside the trailer,

sweeping out the dead critters into the piles

of pine needles, miniature funeral pyres. One night

it got so cold that I considered setting fire

to all the trees, watch them all light up brighter

than that giant one in New York. I didn’t quit

that night— I just never came back, though I

stood out there a long time, broom in hand

fantasizing about the embers flickering

like tinsel, the smell of roasting pine needles.

And when the fire trucks finally arrive

and the police come and ask what happened

I’ll wish them all a Merry fucking Christmas

as the fire jumps to the store front

and say this blaze is my gift

to myself— the only one I could afford.

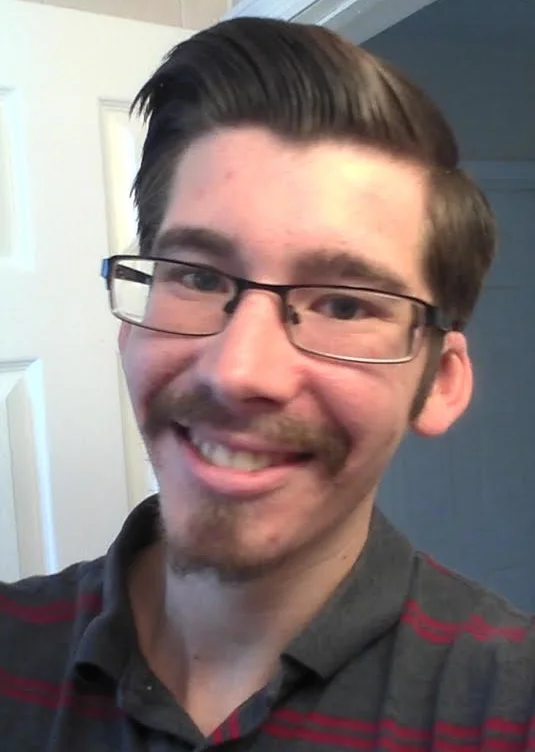

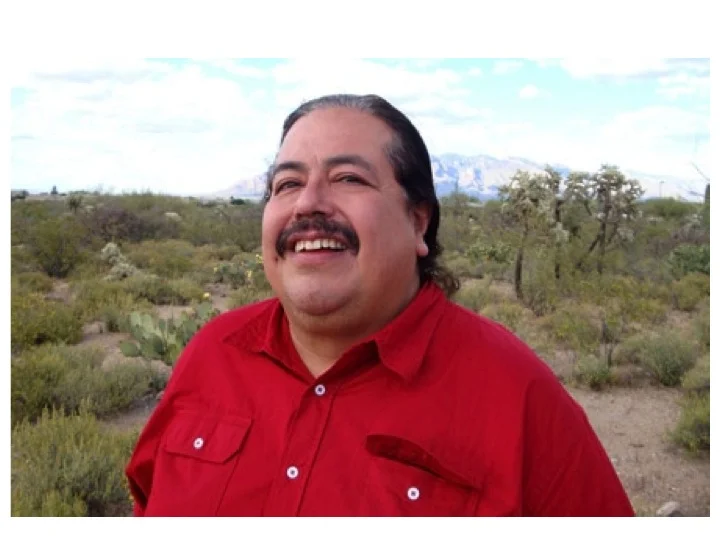

Ariel Francisco is a Dominican-Guatemalan-American poet born in the Bronx, New York, and raised in Florida. He is currently completing his MFA at Florida International University where he is also the assistant editor of Gulf Stream Literary Magazine. His poems have appeared in The Boiler Journal, Portland Review, Tupelo Quarterly, Washington Square, and elsewhere.