An Interview by Dini Karasik

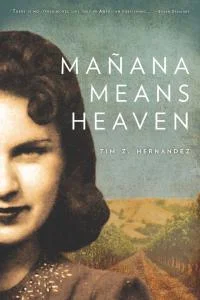

Tim Z. Hernandez is a man of words. And art. And activism. Here he discusses his approach to writing and the arts, his commitment to literary activism, and his latest novel, Mañana Means Heaven (University of Arizona Press, 2013), based on a true story about a woman who falls in love with Jack Kerouac after a chance meeting on a Greyhound bus in 1947.

ORIGINS

You have a multifaceted approach to art. You are a poet, a novelist, a visual and performance artist. You don’t stick to one path as artists sometimes do. Why do you think this is?

-Tim with Lance Canales, Deportee Memorial Benefit, April 2013. Photo Credit: Joann Chacon Avila

HERNANDEZ

My first exposure to art was via performance poetry. In the San Joaquin Valley, back in the early 1980's, there used to be this annual poetry recitation contest for all elementary students. It was called the Peach Blossom Festival. Hundreds of kids would memorize popular poems and compete. Imagine that! In the middle of orange groves and vineyards were these small schools where mostly campesino kids were blasting out Langston Hughes, Shel Silverstein, etc. It was incredible! I suspect the fact that so many writers come out of that region has something to do with this specific program.

-Tim working on fresco mural “Santuario” with artist Juana Alicia, San Francisco International Airport, 1999.

From second grade until fifth grade I took part in this. So from very early on I was exposed to the idea that poetry and performance went hand in hand. When a poem was recited it had to capture the audience. From here it was a natural move into theater. I got involved in theater from elementary school through high school. The whole time I had also been dabbling in drawing and painting. I can honestly say that from kindergarten on, there were alternating periods of years where I was committed to either visual art or theater.

That I had parents who were supportive of all this played a big role, of course. But poetry, or writing in general, didn’t register on my radar until around 1995. After the tragic death of a close uncle, I suddenly found myself adding words to my paintings. An art teacher in college commented that language in visual art was typically considered tacky or gimmicky. I was angry during those years, so rather than heed my art teacher’s advice I rebelled by putting words in all my paintings. I think this is what has continued to inform my approach to the arts in general—rebellion. Who says we can't cross genres? Who says a painting can’t be spoken and poetry can’t be total silence?

In various indigenous cultures there is rarely a distinction between such forms. Poems are dances are songs are food. These delineations, or dare I say, borders, are first world concoctions. Ultimately, for me, art is a free space. A space of total possibility. And it is the last place I would ever want to be stifled by limitations.

ORIGINS

Speaking of limitations, young writers are often told that they should write what they know. Do you agree with this instruction? What is a writer's obligation to himself, the craft, the reader?

HERNANDEZ

I think each writer has to come to these terms on his or her own. It's different for each person. In our process, if we stick with it long enough, we build our own philosophies about why we write and who we write for. Around 1997, the late poet Andres Montoya and I were having a conversation one day, and he asked me about a poem I had written. I was trying to articulate to him what it was about and when I was done he leaned his head to one side and sort of chuckled, then said, “What's your purpose, bro?”

I think this is the question we ultimately end up confronting. What is our purpose? As to the question of "writing what we know/don't know," that's a one dimensional way of looking at it. Things aren't merely black or white. Right or wrong. True or false. Know and don't know. And this is precisely why we write, to work through the complex layers toward some sense of an understanding.

If we look honestly at our own lives, we know this is true. Sometimes I look in the mirror and wonder who the hell that is staring back at me. On the one hand, I know that guy. On the other hand, there are things taking place inside me, tiny exchanges, unjust compromises, molecular wars going on, things I’ll never know about. But again, this comes down to personal philosophy. If I was forced to choose a side I would have to say I only write about what I don't know. I have experiences and impressions about things, and maybe some informed opinions, but I truly, simply, do not know.

So for me, I write to explore the possibilities, and I'm perfectly okay with not knowing. But it’s because of this not knowing that I’m free to write about whatever I want. This is what dictates my approach to subject, form, obligation, audience—the investigations. I suspect every writer wants the freedom to write about whatever piques his or her interest.

ORIGINS

Your most recent novel, Mañana Means Heaven, is a fictional account of a love affair that Jack Kerouac had with a Mexican woman whom he refers to in On the Road as Terry. Turns out, Terry’s real name was Bea Franco and when you found her, she was living in your hometown of Fresno. Tell me about Bea Franco, why you looked for her and how you found her.

HERNANDEZ

First, I have to address the term “fictional account.” There are more than twenty-two books right now that sit on “non-fiction” bookshelves across the world that claim to offer some “truth” about who Bea Franco was. Yet, with more than sixty years of lead time, not one of these twenty-two authors ever once interviewed her. None sat down with her, or came to know her family's history. None looked her in the eyes for hours at a time and listened to her convey her life in an intimate way. None has ever been held accountable by being made to answer Bea’s own questions, and those of her children. And probably, most importantly, none came from the same place and background that she did. My book is the product of having done all of the above. These labels we call “genres” are necessary evils, no doubt, but we can only rely on them for what they are, genres.

As for the question, I got interested in Bea Franco because I recognized her story was valuable and absent and needed to be told. What is not commonly known is that it was the excerpt that Kerouac wrote about her titled, The Mexican Girl, that opened the doors for the publication of On the Road.

With my background and resources I felt I was in a unique position to take this on. Having been born and raised in the San Joaquin Valley as the son of migrant farmworkers, and having worked with non-profits, historical societies and the humanities in that area for nearly twenty years, I thought if anyone could find her it was me. That said, I didn't initially set out to find Bea.

In a hotel room in Sterling, Colorado, putting together the manuscript for Mañana Means Heaven.

In the beginning I was simply researching, trying to find out more about who she was, never thinking she might still be alive. But one Kerouac biographer, Paul Maher, Jr., was very helpful to my cause early on, and he told me about her letters. She had letters housed in Kerouac's archives at the New York Public Library. At the time I was a student in Bennington College's low residency MFA program, so every six months, before I had to be in Vermont, I would fly in to New York a few days early to conduct research.

After my first trip there, when I held her letters, this is when everything changed for me. Still, I began by looking for her children, not her. Of course, when I did find them and discovered that Bea was also alive at age 90, I knew I had lifted perhaps one of the few remaining unturned stones in the legacy that is On the Road. The first three questions out of my mouth, in this order, were, "Bea, has anyone ever asked if they could write about you?" She replied, "No." Then I asked, "Can I write about your life?" She said, "Yes, but I don’t know why you would want to write about me, I'm not so special." And then, of course, this last question: "Can I record our interviews on audio and on camera?" She agreed and that's really the moment that writing this book began.

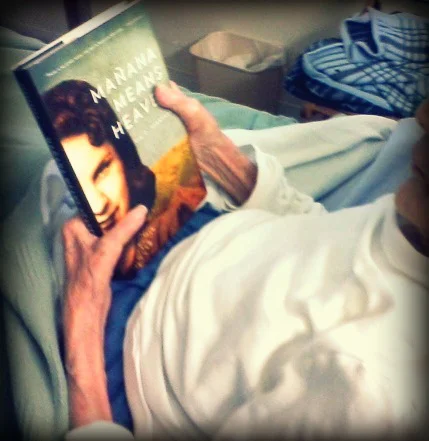

Bea Franco holding a copy of Mañana Means Heaven. Photo Courtesy of Bea Kozera Estate.

ORIGINS

Do you have a sense of what the book meant to her and her family? When she held the book in her hands a few weeks before she passed away—that must have been an extraordinary moment.

HERNANDEZ

Yes, she held the book in her hands for the first time on August 7, 2013. I had sent her family a packet with the book. Her daughter, Patricia, called me excited to say they received it and that Bea loved it. We made plans, my family and I, to visit Bea in Los Angeles at the end of August to celebrate together. Patricia took photos of her mother holding the book and texted them to me. Those would become the only photographic evidence that Bea actually saw her book during her lifetime. Eight days later, on August 15, she passed away. Her funeral was held on August 29, the same day my book was released. It was an auspicious alignment. Her family and I both felt this. They were extremely supportive. In fact, they expressed that the book was a fitting tribute to the end of their mother's life. She lived to be 92. Her son Albert invited me to say a few words at her services. It was a very intimate turnout. She is buried in Belmont Memorial Cemetery in Fresno, California.

ORIGINS

Was finding Bea Franco and telling her story a kind of literary activism?

HERNANDEZ

I believe it was. Anytime we write a story out of the margins, or shadows, it is activism. Anytime we research, investigate, strive toward a revision of our own histories and herstories, a more accurate portrayal of people, places and narratives, this is activism.

For me, this wasn't only about Bea Franco, though. I was also trying to address the community and the landscape, too, in an attempt to correct the eschewed, romanticized, and only partly accurate version that Kerouac depicted. Which is why in my book I call attention to writers like William Saroyan, who was a contemporary of Kerouac yet who wrote about this area with a very real sense of its history. Other writers from this region who have done the same, and in a sense have been literary guides for me, include Phillip Levine, Juan Felipe Herrera, Larry Levis, David Masumoto, Mark Arax, and more recently, Lee Herrick, Andre Yang, Michael Medrano, and Juan Luis Guzman. Read any of these writers works and suddenly Kerouac’s depiction of the San Joaquin Valley and its people will appear as it truly is—a fabrication in the service of his own narrative.

ORIGINS

After you met and got to know her, I imagine you went back and read Kerouac’s account of their meeting and subsequent romance. Did you have the benefit of any additional information from his point of view, aside from the chapters in the book? Any journal entries or notes? Did he respond to any of her letters? Tell any of his friends about her?

HERNANDEZ

Yes and no. I did glean some info from his journals, though mostly just the chronological details, and on a few occasions certain accounts that lined up with Bea's recollection. Bea herself was my primary source and sole focus. I wasn't interested in a Kerouac-centric narrative or his account of the "facts," because that would be doing a disservice to Bea and her story. I took her account as truth, even if it was in conflict with his, or rather, especially when it was in conflict with his. Why should his truth be more accurate than hers? Why should his memory be more reliable? This was my approach. In her letters to him she wrote that she had received a couple of his letters, which means that, yes, he did write to her. Though we never found these letters among her possessions.

ORIGINS

The story is told from alternating points of view, often on the same page. What went in to this artistic choice?

HERNANDEZ

I needed to use an omniscient narration because it allowed me more flexibility in terms of the amount of information I could include. Also, in some instances I wanted my book to be a direct response to Kerouac's account, on both factual and fictional fronts. To do this I had to give myself permission to enter his thoughts too, which is another way of saying, enter his journals. Though I do this with caution and very sparingly throughout because I don’t want the reader to even begin to shift loyalties. The reader shouldn’t have to know anything at all about Kerouac in order to appreciate the story.

ORIGINS

Something that really struck me about Bea Franco’s character was how liberated she seemed for that moment in history. She’s independent but also stuck in an abusive marriage. When she decides to break from her husband, she also leaves behind her children. And when she meets Jack, she is not in a rush to reunite with them. She does, in the end, but as I was reading, I found it hard to relate to her on this front. Can you talk about this dynamic and why it was important to the development of her character?

HERNANDEZ

To fully appreciate Bea's story and the dire conditions from which she was trying to escape, we have to suspend our own judgments. We also have to keep in mind that even though the book is labeled as fiction, when writing it, I was viewing it as a very real depiction of her life, from the flawed or questionable choices to the small triumphs and successes.

Did Bea leave her children behind from time to time? By her own admission, and by the admission of her children, yes. Each time she did this was it a tough decision, sometimes impulsive, but always in service of a greater good, including her own happiness? Yes. Was she regretful about these choices at the end of her life? Yes and no. Would she have survived that stifling situation had she not been equipped with the spirit to rebel against all systems and traditions that forced an oppressive mold on Latina women, then and now? Probably not. We don’t know any of this for sure. But what we do know is that regardless of her choices, she did manage to forge her own way out, meet a wonderful man who would love and appreciate her for the rest of her life, and that her children and many grandchildren considered her the heart of their family. Despite whether or not we find this agreeable or even relatable, these are the facts of Bea's life and struggle.

ORIGINS

The book also depicts the conditions of migrant labor in those years and life in the fields of California’s Central Valley is a theme you often visit in your writing. Can you talk about “place” and how it occupies your mind?

HERNANDEZ

Yes, in whatever genre I’m writing in, a sense of place occupies a large part of my interests. Just like people, place too holds memory. People and place are inseparable. In a physical sense I guess they can be, but just like a mother once tethered to her child, there will always remain an invisible connection that defies logic. To understand place is also to understand its people, and vice-versa. This is why I make an effort to learn as much as I can about the landscape of the place I call home.

Tim interviewing Pete Seeger about his famous protest song, “Deportee (Plane Wreck at Los Gatos),” September 2013. Photo Credit: Anthony Cody.

ORIGINS

In January 1948, an INS deportation plane crashed near Los Gatos Canyon in California. Thirty-two people died, twenty-eight of whom were Mexican nationals. And that's how they came to be identified and buried in a mass grave, as "deportees," victims robbed of their lives and identities. Woody Guthrie wrote a poem, Martin Hoffman set it to music, and Pete Seeger continued to perform the protest song “Deportees (Plane Wreck at Los Gatos) throughout his career.

In addition to writing about this, you've been working to raise awareness and funds for a memorial to honor the victims. Where are you now with this project?

ORIGINS

This plane crash project has been ongoing since the end of 2010. In many ways it's a lot like my work with Bea Franco, except that instead of one person I am searching for thirty-two. So far I have found six of the passengers, but month by month, steadily, that number keeps growing.

In the end, it'll be a book about the details surrounding that incident and the lives that were impacted by this single tragedy, not only those who perished, but also the few key musicians who brought that song to light. How the incident went from newspaper headline to Woody Guthrie's pen, to Martin Hoffman's song, to Pete Seeger's recording of it.

While the research is still going on, I've already begun the writing aspect, and hope to have it done later this year...

✺

Tim Z. Hernandez is an award winning author and performance artist. His debut collection of poetry, Skin Tax (Heyday Books, 2004) received the 2006 American Book Award from the Before Columbus Foundation, the James Duval Phelan Award from the San Francisco Foundation, and the Zora Neal Hurston Award for writers of color dedicated to their communities. His debut novel, Breathing, In Dust (Texas Tech University Press 2010) was featured on NPR’s All Things Considered, and went on to receive the 2010 Premio Aztlan Prize in Fiction from the National Hispanic Cultural Center in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and was a finalist for the 2010 California Book Award. Most recently, in 2011 the Poetry Society of America named him one of sixteen New American Poets, and he was one of four finalists for the inaugural Freedom Plow Award from the Split This Rock Foundation for his work on locating the victims of the plane wreck at Los Gatos.

To learn more about Tim, visit his website: www.timzhernandez.com.