An Interview by Matthew Krajniak

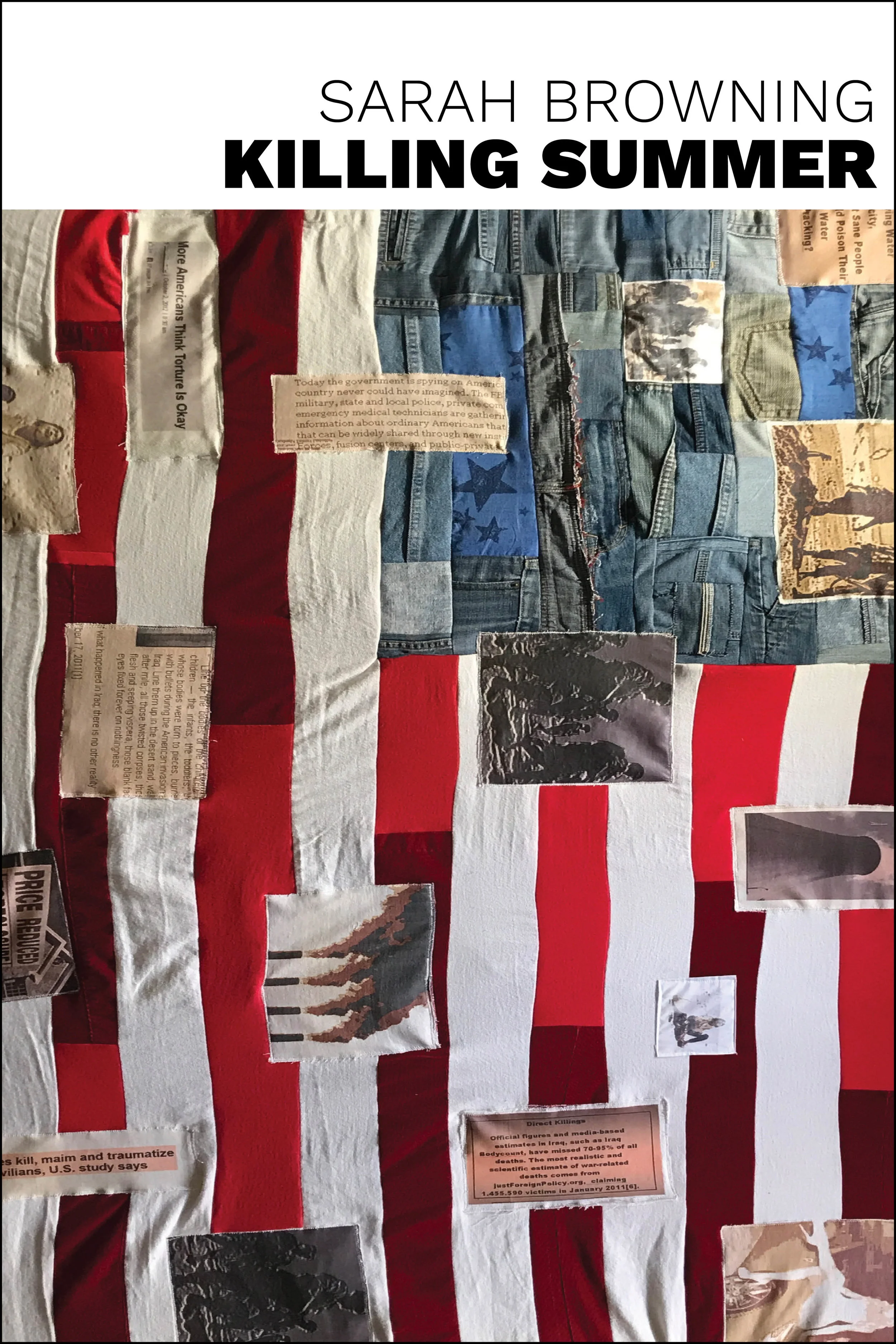

Photo credit: Nikki Brugnoli Whipkey

I feel like I can always use a little insight into the policies of the U.S., a bit of perspective that lends some stability through understanding—even if that understanding is disheartening—but I’ve never felt it as much as I have since January 20th of this year. All of us are aware, at least to some degree, of what’s been going on in the White House and with our government lately, so writing that helps us (i.e. me) engender this internal re-ordering is undoubtedly welcomed. Enter Sarah Browning’s newest collection, Killing Summer (Sibling Rivalry Press). In this collection, we find themes of personal loss and isolation, but we also find plenty of language and ideas that deal with the disheartening and destructive ways our elected officials deal with each other and with those they represent. I had a chance to exchange emails with the ever-busy Sarah (who is also co-founder and Executive Director of Split This Rock) to talk with her about her latest work, her childhood dinner conversations, poetry and politics. Here’s what she had to say.

ORIGINS

Your work in general, but especially the poems in your latest book, Killing Summer, is filled with implicit and explicit political themes, to the point that the reader can get the feeling that you’ve been sensitive to political realities for a long time. Did you come from a family that was politically sensitive? One that argued over trade policies or national security at the dinner table?

BROWNING

You are quite right. I was a child on the south side of Chicago during the late 60s/early 70s – a time much like this one – when politics and social change is in the air we breathe and the water we drink. My father was a civil rights activist and I marched with him against the Vietnam War when I was five. My sister and I sold bumper stickers for George McGovern’s presidential campaign when I was nine.

Critically, too, my neighborhood, my schools, my choir, my church were what we used to call “integrated”: I was a middle-class white girl who grew up surrounded by Black people, who had Black friends from nursery school on, who was frequently the only white person in the room, in the house, at the party, on the bus, who had no idea this was unusual for a white person in America.

ORIGINS

As an extension to that first question, how do you think the environment you were brought up in affected your current passions and interests? And in a more general sense, how do you think the environment of a writer during his or her formative years contributes to their work later on?

BROWNING

I have always been an activist, a concerned citizen, an anxious resident of this beautiful, benighted planet. I assume my upbringing plays a huge role in that. My father is still writing essays and letters to his elected officials and to the editors of his local paper at age 88, a habit I hope to emulate at his age!

I wouldn’t want to speak for other writers, but for me there’s no question that my background informs all my writing, that my lifelong preoccupations were formed by those childhood playgrounds and sidewalks, by the TV news of Vietnam and Watergate, by the gradual, growing understanding of the enduring, vicious strength of racism in our nation.

ORIGINS

What do you think is the role of poetry in politics? Is it a means to create awareness? To stir action? Something else?

BROWNING

Poetry can play many roles, and does. It can help us learn about one another. It can bear witness to injustice, revive our language, such that, as we used to say during the George W. Bush administration, poets remind us that the CIA was not using “stress positions,” it was torturing people.

But also, poetry helps us imagine another world, the one that Arundhati Roy says on a quiet day she can hear breathing. The poet Chen Chen writes, “Let’s build the community garden/that never was.”

ORIGINS

There is a long tradition of politically-charged poetry in the U.S. and the world: Can you speak a little about where you see yourself in this tradition?

BROWNING

I was raised on Freedom Songs from the Civil Rights Movement and political folk songs: Ella Jenkins, the Freedom Singers, Pete Seeger, Bob Dylan. We danced to the Hair soundtrack in the living room at the age of six or so, even though we had no idea “why these words sound so nasty.”

Only later did I learn of the political poets who were working in those decades who I now take as poetic forebears: Adrienne Rich, Sonia Sanchez, Etheridge Knight, Marge Piercy, June Jordan, Audre Lorde, Muriel Rukeyser, Denise Levertov, and others. By the time I came of age as a poet in the 80s, these brilliant, essential poets had been exiled by what I call the poetry establishment – the big magazines, the highly visible teaching jobs and prizes. I was told explicitly not to write political poetry by a professor at Harvard when I was an undergrad in the mid-80s, that this rich and vibrant strain of American poetry was “only propaganda.”

So I gave up writing poetry in my 20s, figuring that what I was writing wasn’t Real Poetry and being unaware of my own tradition. I became a community and political organizer, working to effect change in that way. But I was deeply unhappy, unable to express the complexity of lived experience and unable to probe my own often conflicted heart.

And so gradually, and on my own, I made my way back to poetry and found my way to political poets, haunting used book stores and letting one poet introduce me to another. Eventually, this story leads to Washington, DC, where I was lucky to move in 2002 and find a wonderful community of activist poets and a poetic home, at last. From that home, Split This Rock was born.

ORIGINS

Killing Summer also deals with ideas of loss and connectivity and other deep humanistic experiences: Who are some of your influences, political or not, and how do you find them expressing themselves in your work?

BROWNING

Certain poets I return to over and over: Lucille Clifton, Walt Whitman, Pablo Neruda, Naomi Shihab Nye, Martín Espada, House of Light by Mary Oliver. But also those folk songs of my youth and Episcopal hymns and 70s advertising jingles and my English grandmother’s nostrums and my Southern father’s bad jokes and my mother’s shaming tut-tuts. And all the brilliant contemporary poets – young, mid-career, elder – I read every day, and the rowdy whirligig of my brain. That’s how we all work, no?

ORIGINS

I’m a bit of a process junkie, so I’m curious what yours is. Can you take me through a poem from inception to completion?

BROWNING

I wish there were a standard process. A poem might come in just a couple of drafts or it might take years. When I say years, I mean years – five, seven, seventeen. At the very least, I need time between drafts and I rely on trusted readers, a poetry critique group that lends its eyes and ears to my poems.

Also, I usually don’t respond quickly to events. I deeply admire poets who do, but for me it takes me time. Tragically, of course, violence, war, racism, hatred – these things never seem to go out of style. But then neither do resistance and camaraderie and joy.

ORIGINS

You are also the co-founder and Executive Director of Split This Rock, a socially-conscious literary organization. What have you guys been up to lately?

BROWNING

We’re planning the next national biennial festival, Split This Rock Poetry Festival: Poems of Provocation & Witness, for April 19-21, 2018, which will also be Split This Rock’s 10th anniversary. In this and all our work, though, we’re struggling as everyone is with the daily barrage of tragedy and injustice. Today we woke to the news of the mass shooting in Las Vegas, on top of the criminal negligence of our government toward the suffering in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. And police violence in St. Louis. And… And… How do we respond? How do we move forward? How do we even goddamned get out of bed?

All I seem to return to is poetry. And fellowship. Split This Rock offers both, happily. So we are offering poems from The Quarry, the online database of all the poems we’ve published in our Poem of the Week series and that have won our contests over the years. I offer them to you, Reader: it’s searchable by social issue, so if something has happened in the world that is hurting your heart, you can go to The Quarry and click on “Theme.” You’ll find there contemporary poems that I hope will help express your rage or mourning or hope or all of the above.

ORIGINS

You are clearly a busy woman. Now that Killing Summer is out, do you have any projects, artistic or otherwise, that are begging for your attention?

BROWNING

Sometime in the next year to 18 months, I’ll be stepping down from leadership of Split This Rock. It’s been the incredible work of my life, but it’s time. I’d like to study poetry formally at last and I’d like to write more prose, essays and perhaps a memoir. And I hope there won’t be 10 years between poetry books again!

Also, in my private time, I’d like to help mobilize for change in our nation’s political life. Only a fraction of Americans (25% of adults) voted for the usurper in the White House. Most of us oppose his politics of greed and division. So let’s kick him and his buddies out of office and elect people who really represent the interests of the majority. How about it?