An Interview by Matthew Krajniak

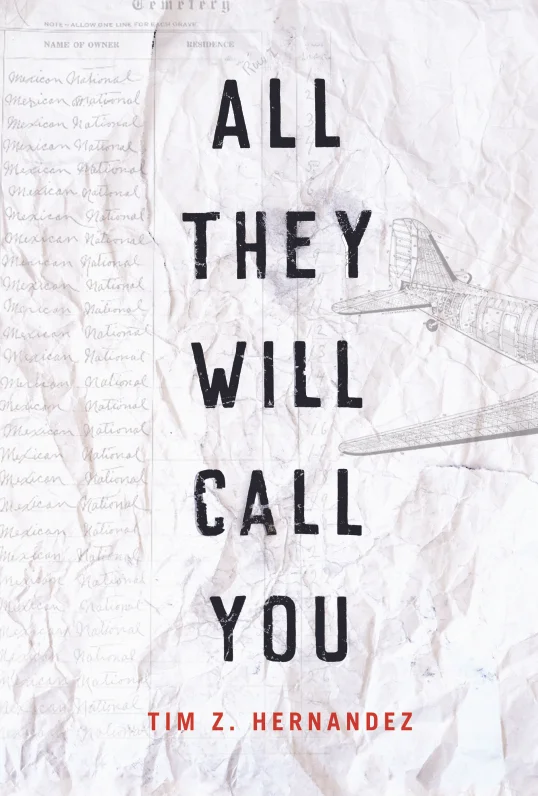

Each human, I would think, has a hope that he or she will be remembered after they die. Certainly some dream of being remembered through a booming and immortal legacy while others simply want a friend or relative to visit their grave occasionally. But what if you weren’t remembered? Or more specifically, what if you couldn’t be remembered because others couldn’t be sure if you’d really passed? Where would that leave your family or your friends or the truths about your life? In Tim Z. Hernandez’s new book, All They Will Call You (University of Arizona Press), Tim investigates and reveals some of the realities for those put in this situation. I talked with Tim via phone to discuss these ideas of being remembered, the truths of a person’s life, and other ideas brought up in this book. Here’s what he had to say:

ORIGINS

In a previous interview with Origins, you spoke of a project that focused on the worst plane crash in California’s history, a project that has since become your latest book, All They Will Call You. What drew you to this incident and how did it eventually become a book?

HERNANDEZ

Well, these kinds of subjects aren’t the ones you can go looking for. They have to kind of land in your lap, and that's exactly what happened here. I was doing research on my previous novel, Mañana Means Heaven, and I came upon this article from 1948 about this plane crash and recognized it was the incident Woody Guthrie wrote a song about called “Deportee,” and that the crash happened right here in Los Gatos Canyon and not the Los Gatos near the coast like I’d originally thought. So I started looking into it, and at first I wasn't even sure it would become a book. I worked for the Humanities Council for many years, so was really looking at it more for its humanitarian factor. Here was a mass gravesite where twenty Mexican passengers were buried, but the site had no headstone because no one knew their names. I simply wanted to find the names and see what it’d take to put them on a grave marker. As part of that project then, I documented everything: what I was doing, who I was talking to, notes about my overall search, so that by the time I found one of the first descendants of the passengers and interviewed them, I thought, man, this is a book. A book because not only is it a distinctly American story since it's tied to Woody Guthrie, one of the greatest American songwriters, but also because it's very much a Mexican story due to the deportees, a subject which is definitely relevant to the world today. Not to mention the story has this built-in mystery of the names and the people and what happened to them. It was all just so compelling.

ORIGINS

As a novelist, poet, playwright, musician, and multimedia artist, you clearly have a passion for exploring compelling projects through other media. Does All They Will Call You have the potential to be explored in other ways?

HERNANDEZ

Absolutely. In fact, it already is a multimedia project. Before I even found any of the families, I invited a friend of mine, a musician named Lance Canales, to play “Deportee” at the Steinbeck Center in Salinas where I was doing a presentation about both storytelling and the crash, and he changed up the song’s arrangement so I could read the passengers’ names at a certain spot. What was interesting though, was that at this performance Woody Guthrie’s daughter happened to be in the audience, which we didn’t know about beforehand. She was in tears during the performance and then came up to us afterward and introduced herself and urged us to continue our work. It was pretty special. So, yeah, this project has had music with it, oral storytelling with it, and then I started to work on it as a book and, then in 2013, I successfully led a fundraising effort to install a headstone. Plus we’re planning to release a documentary in the fall and there’s a mural going up right now, so this project has had any number of shapes and forms to it.

ORIGINS

And like the many forms this project has taken, it also was derived from a variety of forms and sources: letters, government documents, interviews, etc. What was your strategy for approaching and assembling all this disparate information?

HERNANDEZ

What I’ve learned, particularly in the last two books as they drew from other people’s history, is that I need to write the story and what’s happening outside it—for example, what I’m doing everyday. So for All They Will Call You, I kept a journal about my research and included my worries relating to the search for these people, not knowing what the book was yet and only that I had to generate as much material as possible. While doing this, I was also transcribing the oral histories of the families and eyewitnesses to the crash. Plus, sometimes, when they were recalling these memories, my mind would kick off and envision a reenactment, and I’d allow myself to write a kind of reimagining of what was being told to me. At that point, I had these three different narratives going on, but I also had all the language that came from the research itself—the documents, the papers, the letters, the postcards—and again I just told myself to let the story emerge from the material. It was a lot. That said, one of the things I knew right away was that the Ramirez family would become central to the story. They had the most information via documents and memory, plus they were the most accessible being right here in Fresno, and they also knew some of the relatives of the actual passengers.

ORIGINS

Speaking of documents and other hard evidence, in the Editor’s Note you mention how the documented facts of the crash couldn’t be prioritized because they were often wrong, and that, more importantly, facts don’t tell the whole story anyway, that in effect oral storytelling, despite its reputation for getting hard data wrong, is somehow more accurate. Can you speak to that?

HERNANDEZ

Sure. Well in storytelling, in oral histories, we rely on memory, which puts back the mark of humanity and what it means to be human. Facts are one dimensional, finite, so they don’t give any depth or margin for error. What I wanted was this book to be about the humanity of these people, and not the facts, which are equivalent to words like “immigrant” and “illegal alien”—ideas that are very limiting. It’s like Studs Terkel says in the epigraph of the book, “…in their rememberings are their truths.” To me that was essential to all of this—I'm going to go by memory, since it’s a human experience and not just facts on paper.

ORIGINS

After six years of submersing yourself in these oral histories, have you found the form to have strengths, advantages over text narratives?

HERNANDEZ

University of Arizona Press

That’s a complicated question, but ultimately I believe that any story is going to find its readership, its audience, and the discussion it’s supposed to be in, so I think both forms have the same amount of pull. What I've discovered, though, is that I really enjoy the process of gathering oral histories, of talking with people because if I were to focus on just the final print book, I would miss a lot of those interactions and conversations. My books have always been just an excuse to go out and talk to communities, to create a dialogue, so with my previous books like Breathing, In Dust and my poetry, I write them and then I go out and engage in discussions. With the oral history being the text’s source, however, I go straight to the source itself and get to have those conversations every day as part of the process. So to me that's the benefit of oral storytelling. And in fact what I'm looking to do next is less about the writing and more about gathering the stories period and archiving them.

ORIGINS

Do you think that because much of your source information was received through interviews, through these very personal face-to-face interactions, that the tone or shape of the narratives changed?

HERNANDEZ

Definitely. I mean, the personal connection aspect has its pros and cons, but, absolutely, it changes the narratives. This is what I teach my own students, that the more we can go to the source of whatever our subject is, the better and more real and authentic our writing becomes. So for me, getting to know the families, sharing meals with them, being invited to their homes to play with their children, smelling the air that surrounds them, all of these things help imbue the text with that essence of who they are. That said, the biggest con is always having to write the truth of people’s realities. Everyone wants to see themselves favorably, so sometimes I have to negotiate not only with the narrative on the page, but also with the families, especially when it comes to difficult subject matters. For example, there’s this testimony by Guillermo Ramirez who’s alive and a wonderful guy here in town and now a citizen, but he came across illegally. And he told me the story of how he came here and I asked if I could tell it, and he said absolutely, but that I had to make sure I got it right (laughs). Those are just some of the negotiations I had to make. Sometimes families are not OK with certain things and those things I had to leave out.

ORIGINS

So did existing in this world of unresolved grief take a toll on you after awhile? How did it influence your writing process and your own perspective and feelings about the incident?

HERNANDEZ

Well, I've been here for three generations now, with my parents and grandparents born in Texas, so I don't share that more-recent immigrant experience, and I felt pretty objective about my writing. At the same time, however, I've been immersed in this work for many years, so obviously I have a lot of empathy. And working everyday with these people and listening to their grief was challenging—many of these interviews resulted in emotional upheavals when I'd show them documents concerning their lost loved one. Remember, lots of them never knew what happened to these uncles, brothers, fathers. I was like the bearer of, maybe not bad news, but certainly news that triggered grief they’d been holding onto for a long time. Usually when I first talked with the families, they’d shed tears right away and then I would pause and let them gather themselves before continuing. That was hard, knowing that the rest of the interview was going to be so emotional. I’d go home afterwards and was so busy with the work of writing that I didn't have time to process those interactions or my own emotional state, and it wasn't until after the book was done that I realized I needed to decompress.

ORIGINS

On the flip side of that, there must have been some pretty good moments.

HERNANDEZ

Oh, absolutely. There were many very rewarding moments, fulfilling moments because most of these families didn’t know how to go about finding information or the right people to talk to. They didn’t have the resources to find out about a headstone, or even that there was a mass gravesite, so they were very grateful that I was able to help out with that process. So while this project did take a toll, I’ve recently started to feel the clouds part, especially because the families have received some closure through the book. Their grief has been given a chance to pass.

ORIGINS

This idea of time standing still is present throughout the book, an idea illustrated by the fact that these men and women were simply trying to earn a better life for themselves and their families—a reality that very much exists today. Do you see any differences between this pursuit then and now?

HERNANDEZ

Not really. The mode of how you’re coming across now is different, but you're still entering in some cases legally and in other cases without papers and documentation. And you’re still coming up here to the San Joaquin Valley for work. I can go outside my house right now and see farm workers lined up and down the orchard rows, just as people did in decades past. And some farmers treat their workers good, others not so good, and workers still skip from one farm to another because they think a different farm will better meet their needs. Plus they’re all still hard working and come from hard working families, who they still send money to. Not to mention the threat of deportation, which has loomed over this part of the world for decades, almost an entire century at least, and it’s still that way today, especially now with this new administration coming in.

ORIGINS

You also relate how those of European descent had struggles in their native lands and similarly came to the US for a better life, which parallels the narratives of the Mexican nationals. What was your thinking in doing this?

HERNANDEZ

The idea was pretty simple: to show that we are more alike than different, just like the Mexicans and Europeans on that plane were. We’re all on this Earth together with the same fate, all on a ship being deported to that other place in the sky. So the idea was to say that, regardless of where we come from, regardless of our racial makeup or our social status or our religion or whatever our beliefs are, none of us is spared our fate in the end. Same goes for the immigration conversation—we're all in it together. I show that not only with Bobby and the pilot, but also in the beginning of the book I point out the reporter who was from Scottish immigrants, and the photographers who took pictures of the crash that day were Canadian immigrants, and I try to point out all along the way the immigrant parts of the narratives. Even the eyewitnesses came from migrant farm workers who came from Oklahoma. Everybody involved came from immigrants, which points out that those immigrant/non-immigrant delineations, those man made delineations, are kind of a joke.

ORIGINS

This idea of knowing ourselves is present throughout the book, notably when Guadalupe’s grandfather was appalled that Guadalupe didn’t know his people’s history and then later when you relate how the enormous turnout for the headstone commemoration made you aware of yourself and your own family. Has this book and the challenge of writing it somehow put you back in touch with yourself, your family, or your ancestry?

HERNANDEZ

Well, I've been mining my life, my family, and my interests for all my books, so I don’t think this one has made me too much more in touch with those parts. What I can say though, is that the process of writing this book did show me a part that my family is out of touch with, which is Mexico. One of my biggest fears, like every second- or third-generation Chicano, has been language because our elders made fun of us for not speaking Spanish despite being here for only three or four generations. And of course I’m generalizing here, but we grew up with this stigma and self-consciousness of whether or not we were really representative of our culture. In fact, (laughs to self) when I went there, I thought they were going to eat me alive. But these families were not that way at all. They were very open and understanding. It was beautiful. And that’s why at the very end of the book the elder says that they do come back. So when I returned there, I felt something very much like redemption, and realized I had to go back into the book and tease out more of my concern about my not knowing Spanish. That’s part of the book after all—it’s part of my search.

ORIGINS

During this search, you also talk about the difficulty of getting information or contacting surviving family members. Since completing the book, have you been able to learn any new information or locate any other families?

HERNANDEZ

No, because I knew my final trip to Mexico in 2015 would be my last real push for research. When I returned, I focused mostly on the writing and told myself that if anything comes across my radar I’d explore it, but that I'm not actively searching anymore. There are at least four other passengers I have information for, three of them include photographs, but I didn't include them in the book at all because I couldn’t confirm the information. I verified identities through these triangulations, by finding three different bits of information that pointed me to the right person, before I included him or her in the book. For these other passengers, though, I could find only one document with their photo, and it would have the right name, birthday, and town they were from, but it was only in the one paper. Ultimately I just didn't have the time, money, or resources to go find them.

ORIGINS

Is there anything that didn’t make it into the book that you’d like to talk about?

HERNANDEZ

Yes. There were so many people who helped me and so many stories surrounding this help that I simply couldn’t include all of them, or even many of them. Those people and events were the most difficult part to take out, and that's why there’s a ten-plus page Acknowledgements section (laughs). My name is on the cover, but every step of the way I had teams of friends, families, and strangers helping me. Thing is, to add them all in becomes this crazy long narrative of just contextualizing, so I had to cut much of it out. For example, when I went to the Navajo Reservation in Arizona and camped there with my friend and a team of people, they showed me around and took me into the Navajo school where we spoke with the school faculty, and I couldn't include each of them because it would move the focus off the story and take like twenty pages. And this happened in Mexico and New York and many other places. And in each case it's like I was there by myself, when in reality a team of people was helping me. So that’s why I have such a long Acknowledgments section—I needed people to know that many, many people helped me along the way.

Tim Z. Hernandez is an award-winning author and performance artist. His debut collection of poetry, Skin Tax (Heyday Books, 2004) received the 2006 American Book Award from the Before Columbus Foundation, the James Duval Phelan Award from the San Francisco Foundation, and the Zora Neal Hurston Award for writers of color dedicated to their communities. His debut novel, Breathing, In Dust (Texas Tech University Press 2010) was featured on NPR’s All Things Considered, and went on to receive the 2010 Premio Aztlan Prize in Fiction from the National Hispanic Cultural Center in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and was a finalist for the 2010 California Book Award. In 2011 the Poetry Society of America named him one of sixteen New American Poets, and he was one of four finalists for the inaugural Freedom Plow Award from the Split This Rock Foundation for his work on locating the victims of the plane wreck at Los Gatos. All They Will Call You is his newest book.

To learn more about Tim, visit his website: www.timzhernandez.com.