“All I must do now was stay sound and good in my head until morning when I would start to work again.

—Ernest Hemingway, A Moveable Feast”

In the fall of 1992 I began attending Purdue University as an English major. I was a first-generation college student, and I was trying to take an imaginative leap outside my family and class. Books held no value in my family, and though my mother attended night school to receive her GED, my father only had a third grade education. My parents never had any advice, wisdom, or financial means to help me. These are my origins and I felt at the time that I needed to escape them.

I had spent the previous eight years working many jobs: grocery clerk, gas station attendant, water-well driller, carpenter’s helper. A few months before attending Purdue, I worked a 12-hour night shift in a factory, a job I held for five years. At school I had all this time on my hands, and I worried over how to survive beyond the first year on the $3,000 I had saved. There were moments of boredom, days when I didn’t know what to do. Sometimes I would begin to sweat, my stomach queasy as I experienced what must have been some kind of shame because for the first time I could do whatever I wanted.

That November I would turn twenty-six years old. After two years of classes at a community college and a small university, I moved from South Bend, Indiana down to West Lafayette to attend Purdue full-time. I was a Puerto Rican-American who didn’t understand what that meant to others, and I was just beginning to struggle with what that might mean to me.

What I felt, more than anything, was that I wanted to write. Nothing in my life seemed to offer the possibility, imagination, or gift of language to have a life of writing; it was if I were moving to another country with only the clothes on my back. At the age of twenty-two, I had discovered a love for words, lost days reading them, spent bright mornings writing them.

There was a mysterious energy that arose from the page as I composed small paragraphs and vignettes. My childhood returned to me in motion. Hartford, Connecticut. Niles, Michigan. Añasco, Puerto Rico. Back to Hartford and off to Michigan once more. These places sprung to life and with them people whose words and actions were vividly imprinted in my memory and imagination. There was texture to this life, strands of work, migration, music, food, and languages I didn’t know how to weave together. For the first time in my life—free of my father’s alcoholism, free of the poverty and unpredictability of childhood—I felt a sense of purpose. I wanted to write and I needed someone with more experience to help me know what I had to do to become a writer.

When I first tried to meet the writer and teacher, Patricia Henley, at Purdue University, I made the mistake of asking for the wrong person. An advisor had recommended I inquire about enrolling in one of Patricia’s fiction workshops. But when I called the English department, I mistakenly remembered the name as Beth Henley. I asked if she was in. It was the middle of summer, of course she was not in, and there was no “Beth” Henley. Perhaps I was looking for Patricia Henley? The first writing I had ever done was a play on a manual typewriter, and maybe that caused me to remember the playwright’s name. I was told to wait until fall classes to talk to Patricia Henley.

My second mistake happened when I went to meet Patricia that fall. With a stack of story manuscripts in hand, I stood outside her afternoon class waiting for it to end. The door opened, students streamed out, books against their chests, their sides, pencils or pens between fingers, talk growing louder in the hallway. There was a break in the current and I squeezed through the door, stopping the line for a moment. Patricia stood at the podium straightening papers and talking to some students. I didn’t wait for them to finish and rushed up, my manuscripts held high, ready to talk fiction writing. I told her I had been writing for the past year, had just started at Purdue, and wanted to keep writing. I waved my manuscripts as I spoke. I don’t remember if she took them to read. I want to say it was then—standing there at the podium listening to my crazy or passionate talk—that she said I could join her spring workshop.

That fall I became even more driven to write. Meeting with Patricia fueled my desire to write even more. I attended classes, put in the hours of reading and studying to complete my schoolwork. Every morning I was up at dawn, showered, and ready to go. Outside, in the cold morning air, I sat on the Memorial Union steps reading and writing in a notebook. After a day of classes and studies, I would sit until twilight at an outdoor cafe table and over a few cups of coffee read some more fiction or a book of essays, and write whatever my imagination turned towards. That fall’s golden light lasted forever. At one point, I wrote a short novel in four days.

I met with Patricia a few times to discuss writing and writers. I felt a fundamental shift in my identity, which brought into focus the conflict between my working and student life. I often had no idea what I was trying to do or express. All I wanted was a life of writing now but I didn’t appreciate all the reading and writing I still needed to do, the years of apprenticeship required to make this life of writing a reality. I shared my confusing thoughts and feelings with Patricia. I said something like, I'm not sure this is for me. I’m thinking about leaving. Her eyes and face were hard, serious. She said something like, Well, it wouldn't be the worst thing in the world. Going out and working never hurt a writer. Patricia let me know that I needed to choose what was best, especially if I felt I didn't belong. The way she said it suddenly scared me. She was giving me the freedom to decide. No one was stopping me. Just two months before, I had quit my full-time job. If I left Purdue I had nowhere to go. Outside Patricia’s office I felt even more unsure, frightened by my choices.

Why had I decided to talk to Patricia? There are some things you cannot share with others, even your closest friends.There are secrets one must struggle with. My upbringing, being a first-generation college student and my work were experiences I couldn’t easily share. I couldn’t envision how my past was relevant to my learning, writing, and life. I had never had any guidance about such things, and I felt I had to hide who I had been in order to make the leap into a college education.

To get me through this period of intense self-doubt, I needed the help of an experienced and mature writer, someone who could help me see the value of my words. Someone who would encourage my writing. Someone who wouldn't allow me to make excuses. Patricia became that someone. As my mentor, she filled my days with many possibilities for reading and writing, and she challenged me to do whatever it took to live a writing life.

Patricia began each class by reading a writer’s words or an anecdote of biography from a daily calendar, and this small act provided a glimpse into the unstoppable history and life of the written word. In workshops she read from a story—a passage, a few sentences—to illustrate an important element of craft for that specific day. She introduced to me to writers like Raymond Carver, Andre DuBois, Richard Ford, and Katherine Anne Porter. It meant the world to me to encounter writers who were grappling with the burdens of family, class, and work. I sensed authority and authenticity in each of the writers Patricia introduced; they, too, struggled with place and identity and in ways I wanted to understand. Katherine Anne Porter, for example, wrote such beautifully detailed and compelling stories set in Mexico, which she described as her “much-loved second country.” Porter was but one writer who helped me think about my identity and writing in exciting and new ways.

In the 1960’s my father, along with a handful of other Puerto Rican men, migrated to Niles, Michigan to work for the Green Giant mushroom cannery. These men became pages in a book I’m still trying to read and write. Across the street from my childhood home was the Puerto Rican House, a gray two-story duplex where the men gathered on the front porch to drink, talk, and tell stories. A man leaning against the black aluminum porch column, one leg crossed behind the other, his arms folded over his white guayabera, a fedora cocked on his head, a cigarette dangling from his lips. A man sitting on a weathered fruit crate, his legs wide, and his crooked hands clasping his knees. The roar of laughter. Two or three crinkled paper bags holding tall cans of beer or pints of rum. They talked, laughed, drank and watched the world pass by. They watched as I threw a rubber ball against the front steps, played imaginary games of baseball in the side yard, throwing ball after ball into a flimsy net backstop, or sat with my back against a tree staring at the grass or looking up and following a trail of clouds. Whenever we left or came home, there they were, watching. I knew nothing of their lives, nothing of what it must have been like for my father to live in this town as if shipwrecked, so far from his island home. This "Puerto Rican House," this childhood, has always existed in my memory and imagination as a much-loved second country. This is the country I started to claim and write about at Purdue with Patricia as my mentor.

Back then I was a sponge and a songbird. I took in everything I read and held it close. I was exploring, learning, practicing, and the best way to begin as a writer is by playing another writer’s music. Patricia listened carefully, and she heard my emerging style and voice, my music. She read every manuscript I gave her—too many to count, too many I should’ve held on to. My lyricism was often unbound, which led me to write long, complex sentences. When I enrolled in college at the age of 23, I struggled with English proficiency and grammar. I never felt that Patricia saw these as problems. Instead, she took me under her wing, helping me hone my skills so that my sentences possessed more elegance, grace and power. I can still recall how much creativity I gathered as Patricia took me through the use of em dashes and semicolons, both of us hunched over the sentences of Alice Munro, Richard Ford, and William Trevor. Through this kind of reading and writing she taught me the joys of craft, the solitary pleasures of exploring the life of a sentence, and the sea change you experience when you are able to identify and touch in your mind what Raymond Carver called a writer’s "unmistakable signature." She affirmed my love of words, reminded me why I loved to work with them and how a love for words is not enough to become a writer.

Recently Patricia wrote in a letter:

““You were on my mind this morning because I find that I’m starting my novel over again. You stand out as a writer who is always willing to do that [start all over]. There’s no way around it.””

This fall I’ve had many days that lack purpose, that don’t burn with the lyricism, passion, and magic that used to propel me into writing. I’m digging deeper into that old secret, into who I was and how it is that I’ve become a writer who has one foot in the Midwest and one foot in the Caribbean, a writer caught between two much-loved countries. In writing nonfiction, I’ve lost the mask of my invented characters and narrators, and to stare at the blank page without them is a great challenge of emotion, vision, and language. I find that the past is filled with too much loss, too many wasted years, a younger self I cannot save. I write images and memories that flounder in a turbulent sea. Too often the pieces I write seem fitful, false, freighted by the effort. It’s as if my many years of writing have been a lie because I can’t seem to trust the process, can’t trust that the writing itself is the way. I question every decision. Write pages that seem worthless. I know I have a story to share, but then there’s always this other voice asking, Who really cares about that story?

Patricia once wrote at the end of a manuscript words I will never forget. Just keep doing what you are doing. She meant that I should continue reading with passion, writing the characters and places that matter to me, and imagining writing as an act of discovery. In this way, my writing teaches me how and what I am writing. As I write today, here she is, my mentor once again, sitting beside me as I look over the sentences, telling me I know how to begin, that all I need is to just keep doing what I am doing.

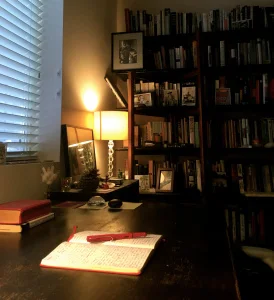

About a year ago Patricia retired from teaching. She sent me a package. When I opened it, I was so surprised and moved to find a beautiful framed photograph of Ernest Hemingway. She always found his writing an unfailing source of inspiration, work ethic, and craft. I once shared with her that, when I was beginning to dream of writing, I would spend days reading Hemingway and chasing his ghost up in the northern Michigan towns and woods of his youth. In the photograph Hemingway is slim, moving closer to death, wearing a plaid wool shirt. He’s in Idaho, in 1959. He’s standing next to a dresser that has a specially made top so he can, as he did for years and years, stand while writing. He’s holding a pencil in his right hand and his left arm is resting against the manuscript pages, the sentences he’s working on visible. I imagine those beginning-to-curl pages are from A Movable Feast. In his face, in his stance, I feel the magic of writing. Looking at the photo I remember as if it were a dream, sitting in Patricia’s office on the fourth floor of Heavilon Hall and Hemingway up on the wall, looking down as Patricia and I move through sentences, clear and swift as a cold stream, lush and rolling like a green summer field.

Hemingway now looks down on my writing table. When I look at him I remember Patricia’s many gifts, and how some twenty-two years later she is still my mentor and friend. Patricia fostered and affirmed my writing life. She helped me hone and craft my lyricism, develop my written art, and deserve my origins.

In the morning when I sit down to write, I am following a tradition of mentorship and writing, a tradition of desire and possibility and accomplishment. Mentorship continues on. As I write, those who came before me look down with encouragement. Together, we move towards a second country.