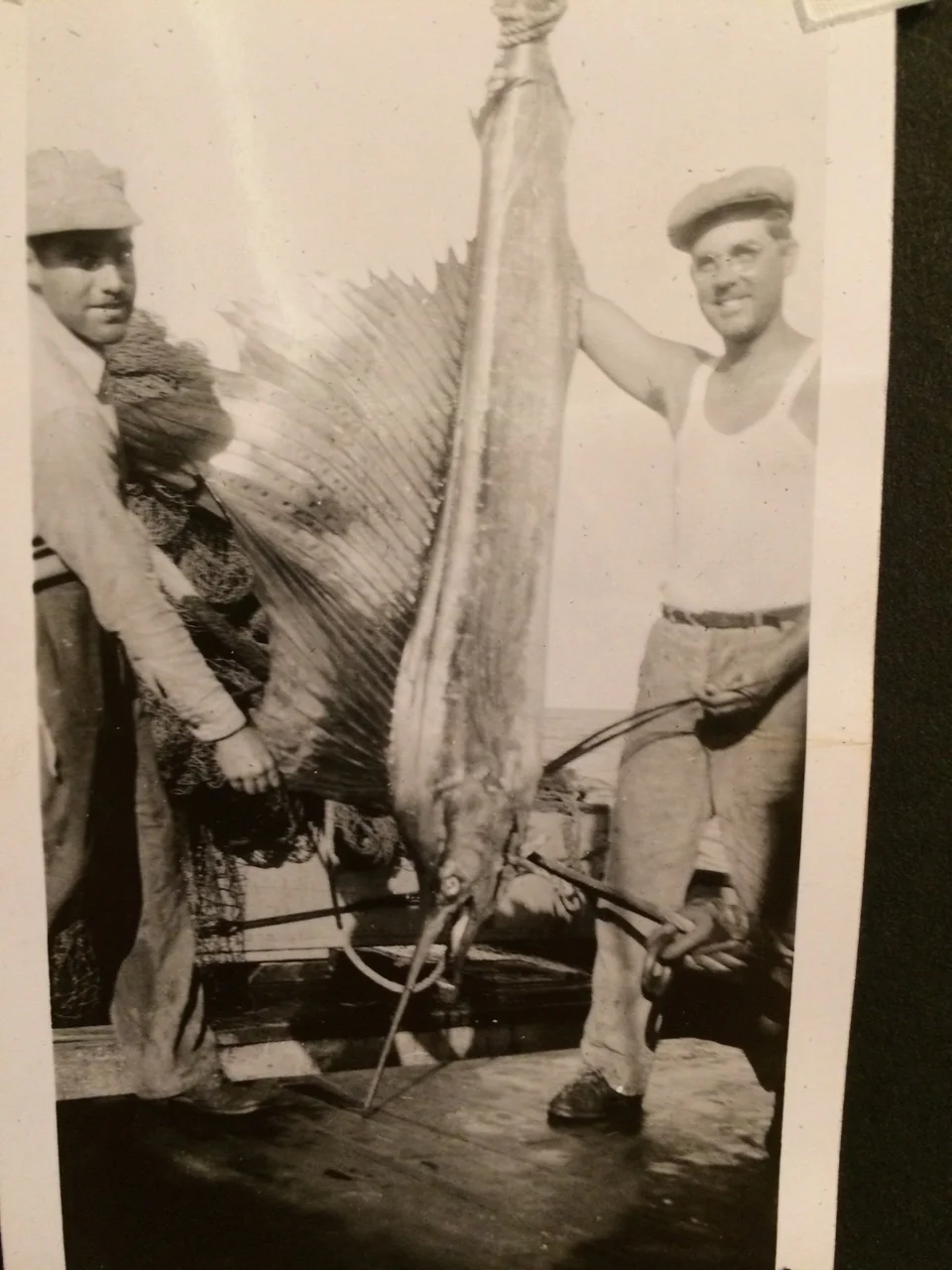

My grandfather on the right.

My grandfather was a one-eyed fisherman who arrived as a boy with his family at San Pedro just after the days when it was part of the larger Rancho San Pedro of old Zorro episodes, the sheltered little bay that soon became a nautical mecca for the fishing tribes of Italians, Slavs, Japanese and Mexicans who made up the town’s early DNA. The Slavs, for example, ethnically Croatian but part of the larger Austrian-Hungarian Empire at the time, worked their way across the United States as miners, headed for Puget Sound to fish the salmon, froze off their asses in the wet 30-degree air, and headed south. San Pedro looks and feels very much like the Adriatic Coast, or even the Amalfi Coast if done cheap Slav style. Slavs are notoriously cheap, which is important to the story.

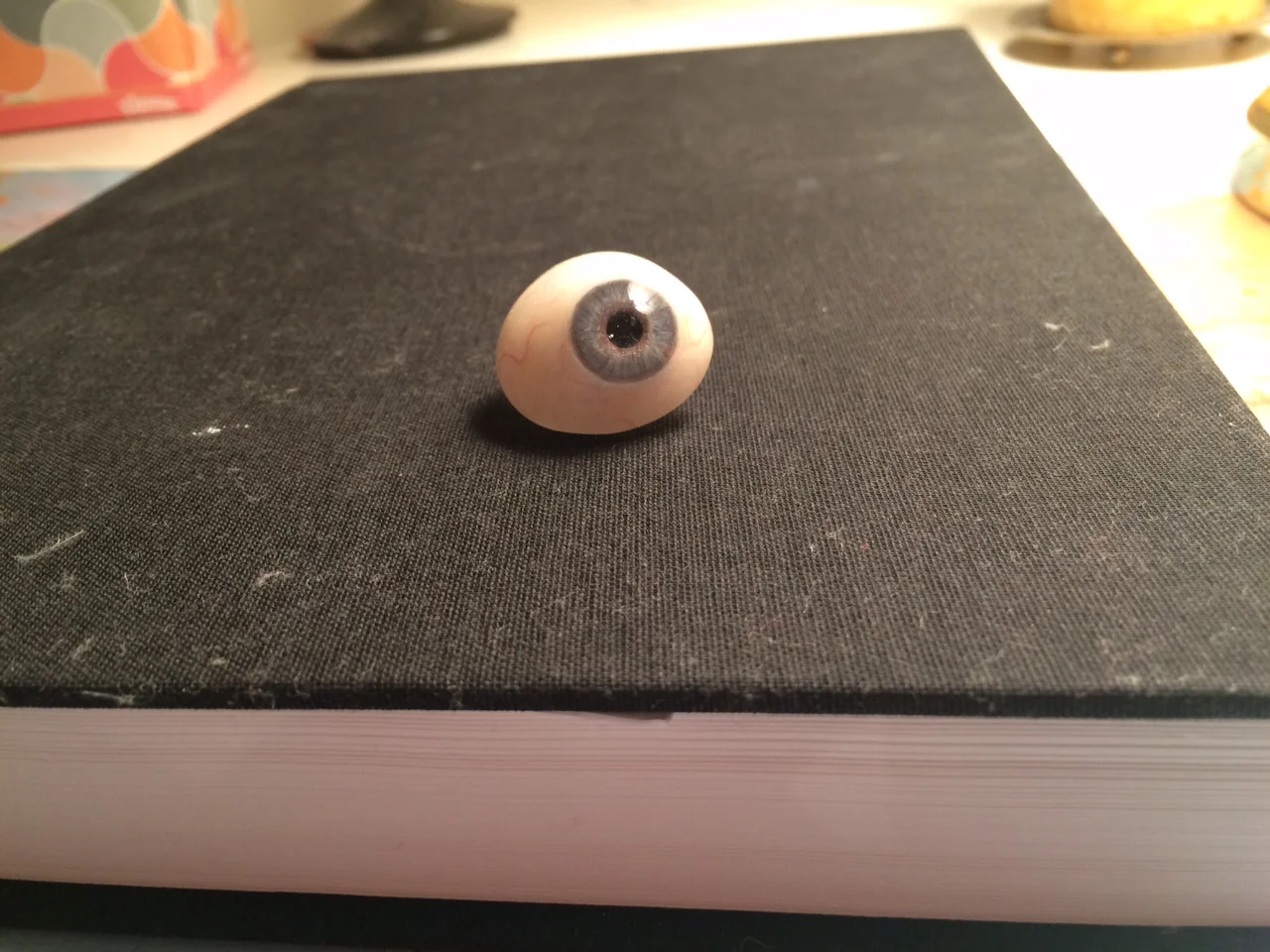

It was automatic for my grandfather to become a fisherman, really, and not because of his missing eye. As much as we’re used to the image of the old salt with an eye patch, that had less to do with covering up a dry socket and more to do with an early method of night vision for pirates, keeping an eye in constant darkness when taking prize ships, flipping it over for do-it-yourself infra-red for successful below-deck pillaging. As for fishermen, well, it was probably always better to have both eyes, although my grandfather proved that binocular vision wasn’t essential, and he didn’t have an eyepatch, he had a glass eye. One he’d had since he was a young boy, one he might not have needed if his mother hadn’t been a cheap Slav. In a way, the eye has its own fish story.

My grandfather is dead now, and I keep the glass eye on my writing desk, and it gets caught up in all sorts of shenanigans. (Not a Slav word, but we’ve assimilated.) I send friends photos of the eye in different places as if it’s the Travelocity gnome or Carmen Sandiego. I stick it onto my eyelid and freak out the kids in the family. I have it stare at me while I work at my computer as if to remind me what real work is. My grandfather saying, I fed hundreds of thousands of people over several decades. What have you done today? With both your eyes? My grandfather never would have said that. But still, it is an eye of judgment all on its own.

Different versions of the eye story circulated throughout the years, all of the narrative summary variety. I’ve cobbled together the known facts and here’s how I reconstruct it: A group of cousins, all boys here, all between the ages of eight and fourteen. Their fathers, fishermen all, have caravanned down the westernmost artery of the country and built themselves new boats, or partnered together on boats, or worked on other boats until they saved enough to partner together on boats.

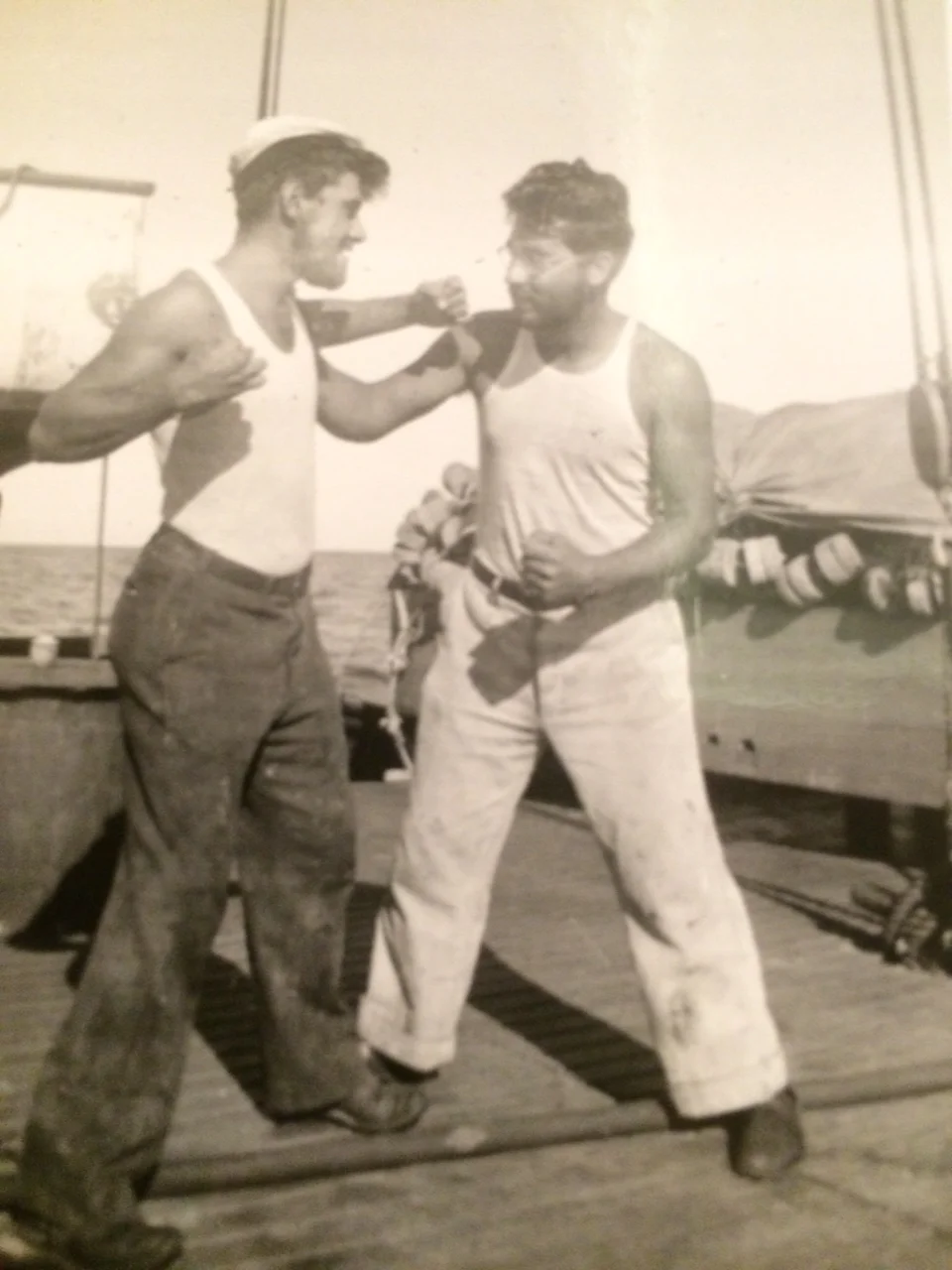

The time is about 1920, and my grandfather has just acquired a second digit to his age. This is a big deal for a boy in the wilderness, because that is where they are. San Pedro is a tight little nugget of wood-framed houses just outside the dangerous Beacon Street area, where there is more than one brothel, unofficial “boxing matches,” we’ll call them, and general scrappy tomfoolery that ends in bruises and bloodshed. But just removed from the scandalous Beacon Street and the sphincter-tight homes just above, are fields and fields of tall grasses and Japanese tomato and strawberry farms, and beyond those, more wilderness, perfect for hunting rabbits. A lot of rabbit is eaten in these times.

My grandfather on the right, on a fishing boat with a cousin. Possibly taking revenge for the eye?

My grandfather spends most of his time with his cousins, who have names that end in –ich, or even still –ić before Americanization takes hold. (Even today, there is a sense of pride among the holdouts, and the Dragićs, Katnićs, Kostrenčićs, and Something-or-other-ićs let everyone know they aren’t Dragichs, Katnichs, Kostrenichs, and Something-or-other-ichs. My grandfather's is the odd one-syllable name, which then was Car. I still get flack in town when I run across Cars who say, We only have the one R, as if I’m the prodigal relative, or that R is painted scarlet on my chest.) So in the wilderness, this pack of cousins is engaged in some activity around a tree.

This activity happens to be knife-throwing. Fortunately, not the carnival act of throwing knives around a stationary person, or the story might have been worse. No, the simple joys of the bygone era of throwing knives at a tree, watching it stick into the bark, a target scratched on with an X. Some of these boys, being of different ages, are stronger than others. Some are more practiced at the subtle art of knife-throwing. An older one, probably not the oldest, but maybe the second-oldest, the Beta—Beta Cousinich, we’ll call him—goads the others a bit.

Names are called, mostly the derogatory appellation of girl, which is incongruous, since the strongest (and scariest) human beings these boys know happen to be women. But more on that later. The Beta Cousinich likes to tell his younger cousins they throw like a bunch of girls, seeking approval from Alpha Cousinich. Alpha is the oldest—although he can’t be much older than fourteen or he’d be working—and so by proxy he’s the most responsible. He hits his mark every time but sees the game getting a little too aggressive and tries to get the boys to calm down. Wild swings are made. Erratic marksmanship. Overly-hard throws by the middle of the pack -ichs, the eleven- and twelve-year-olds. The eight-year-olds are getting nervous. They are reluctant to take their turns. They stand by while the older Cousinichs, the ones with two digits in their ages, step forward, cheer, groan, hoot.

My grandfather can’t be lumped with the babies now that he’s ten, so he stays close to the action. The knives don’t always stick to the tree. The knives start to bounce. The boys jump back a bit when the knives land at their feet. This doesn’t stop the wild swings. It’s my grandfather’s turn to step forward. He swings a wild pitch, and the blade hits near the bullseye before it falls to the ground with flecks of bark. But he is cocky now, and as Sam Cousinich, his closest cousin in age, steps forward, my grandfather crowds him, the same way Beta Cousinich does. Sam Cousinich swings hard to beat his closest cousin, but it’s a sloppy throw, end over end, and it’s the pommel end that hits the bullseye—then the bounce. This is a higher bounce than the previous bounces, it is the bounce of all bounces. It happens in mere seconds, and a few of the boys lose track of the blade, look for it near the bushes. But Alpha Cousinich tracks it mid-air. He wishes he could stop it, waits for his younger cousin, my grandfather, to jump back. My grandfather doesn’t jump back. And yet, it is a perfect boomerang bounce—I guess you could say it’s the granddaddy of bounces. There is a shout, and Sam Cousinich yelps, and Beta Cousinich says the worst word he’s ever learned, shit. My grandfather is too stunned to say anything yet. The knife has finally stuck somewhere, but in the unimaginable place.

My young grandfather, just around the time he'd lose his eye.

My grandfather’s glass eye is the most realistic piece of appendage-replacement I have ever seen. The iris is nuanced blue with flecks of green and gold to match the original, or the mate, as it were, there are tiny pink veins running across the edges, the pupil is a non-committed mid-sized circle that doesn’t stand out in sun or shadow. It’s not the kind of gigantic freak-show-but-biologically-accurate ball forensic sculptors use, the kind you’ve seen on CSI. It’s small enough to be popped in and out, the shape of half a small walnut shell, a few millimeters thick with a concave back. It fits just inside the scalloped eye socket. I was about ten years old before I knew he had a fake eye, about the story, which I heard from my mother, who heard it from her sister-in-law, later confirmed in a different version by my dad’s female cousin. My father didn’t know about the eye until he was almost out of high school.

The ten-year-old version of my grandfather pauses only a moment to process what has just happened, puts his two hands on either side of the handle, palms together as if to pray, and flings the blade out of his eye. The Cousinichs stare, make a circle around him. Sam sniffles, but none of them talks. Beta Cousinich says it again, shit. This time, Alpha Cousinich backhands him on the arm. That snaps them all back to action, and they rush at my grandfather, they shout, and in the commotion, my grandfather begins to shout too. Two of the middle of the pack –ichs run ahead—there’s a long way to run, just to a road. An adult must be notified. My grandfather begins to feel pain, somewhere welling deep beneath the adrenaline. He holds his hand to his eye, feels something ooze. His hands are filthy. Alpha Cousinich makes a younger boy take off his shirt to give to my grandfather to hold over his eye. The boy complains that his mother will kill him if his shirt gets ruined, but he knows not to go against anything Alpha Cousinich says and so pulls his shirt over his head. At this time, all the boys have shirts made by their mothers. In a few years, before the first day of school, they will order two shirts from the Sears catalogue, two shirts and two pairs of pants to start the new school year. But now, the mothers all make their shirts, and better than any factory could do. Croatian women are expert seamstresses. And bakers. And as these Croatian mothers spend much time alone, their husbands gone to sea, they take care of most household things on their own. This is another important fact.

Four Cousinichs surround my grandfather, one holding up his right arm to guide him through the uneven ground of the sloping hill, one standing behind him, his hands on his back, another holding up his left elbow, the hand holding the shirt to his left eye. Another little cousin circles around the recessional, like a gnat or a puppy, a well-meaning nuisance, but he scouts the terrain to warn the others of rocks or sudden ditches in the ground and so isn’t swatted away by the older boys. Though they’ve never marked out the distance, they have to walk a good mile and a half back to the road. By this time, my grandfather is in a place beyond pain—what he feels is fear. By this time, Beta Cousinich also starts to worry about the bigger issue, how much trouble the boys will be in, and no getting out of it because of the instant ocular proof—pardon the pun—of compounded mischief. There’s always an instigator, and the Beta always risks the most accusation. He’s sure the younger Cousinichs will allot him a greater share of the blame, which isn’t fair since it wasn’t his idea to throw knives in the first place. He only picked the tree and marked the bullseye. And crowded Sam. Alpha Cousinich tells him to be quiet, and for a while, they all are, aside from the sniffles of the eight-year-olds and my grandfather. There’s the issue of drainage, and it affects his sinuses, his ears. There’s an odd and unexpected loss of pressure in his socket. The shirtless Cousinich now decides to run ahead to catch up with the advance guard. But a general sense of dread settles on the whole group and they slow down, my grandfather included, because they all have a general idea of what they’re in for.

Some of the "coven." My great-grandmother is in the center.

The ethnic families of San Pedro live in enclaves, or maybe compounds, and this will continue through the 1960s. Bachelors and newly-wedded couples live in one- or two-room bungalows, on the southern side of town, and once they save enough money inside their mattresses, pay cash for one of the newly built bigger houses up the street a block or two. But they all reside in the same general area. They live next door to one another, across the street, all within short walking distance, just above the reek of the canneries at the end of 22nd Street. Slav women are very careful that their homes don’t smell of fish. They boil their husbands’ clothes when they return from fishing, outside, in the backyard. They have access to cleaning potions that erase any evidence of filth or stench. In many ways, these women are like witches, and with their husbands gone, they raise their children in an obsessive-compulsive, anally-retentive coven. So when the advance guard of young Cousinichs run for help—and reconnoiter—they need only reach one street, one house, to raise the cavalry.

The rest of the Cousinichs leading the wounded are almost to the road when they hear voices, a few cars and trucks rumbling across the blocks of concrete pavement. Nicky Cousinich has a father who makes deliveries from the fish market in the harbor to the markets around town. It’s his truck that’s waiting for them on the side of the road. It’s his voice the boys hear, and they start pleading their defenses. If my grandfather had been able to be a more astute witness at the time, I might have gotten better details of the melee of desperation and terror. Anyone who knows boys of that age can imagine plenty the incomplete versions ricocheting between them. The terror itself is not from losing the eye. Most of them have dealt with worse, including my grandfather, whose half-brother has already died from tuberculosis. Their fathers sail a couple of the seven seas in creaky wooden hulls that could capsize in a medium-size storm. No, more real for them is the homespun punishment and subsequent guilt. It’s an easy jump to imagine the terror felt when my grandfather was loaded onto the truck next to crates of sardines on melting ice and the rest of the boys were left to face their mothers.

One note about my great-grandmother: she’s the scariest person most of them know, and that includes the sailors with tattooed knuckles. But plenty of the other mothers could hold their own in partisan combat. When my grandfather is hauled back to the compound, the boys have to shuffle their way home, knowing deep down it’s best to just get home and get it over with, but hesitating nonetheless. Within a few minutes, or half a block’s distance at the pace they’ve been ambling, the mothers show up. They have wide hips and thick legs—not fat, just sturdy, and they don’t run compared with what their sons can do, but the mothers would call it running. There are four of them, and Beta Cousinich thinks of his father’s stories of how the sharks stalk toward the boats once the smell of blood and the thrashing of helplessness leak into the water. Upper arms are gripped in tight fingers. One boy is greeted with folded arms and a look, and he looks down and walks past his mother, leading the way home. The mothers usually speak in Croatian to their sons, and always when they’re angry. Beta Cousinich keeps his shits to himself. All the boys are herded back to the enclave, and when they pass his house, they see eight-year-old Cousinich looking out his bedroom window, still without a shirt, his mother on the porch to his right yelling, in Croatian, to her sister-in-law across the street, already comparing versions of the story. The boys are not questioned together. This is where the FBI learned their tactics.

My grandfather and fellow fishermen off the coast of South America.

Once the boys are confined to their rooms with bread and water, the mothers converge on my great-grandmother’s house. The uncle with the ice truck who dropped off his sister with my grandfather claimed he had to hurry to make the rest of his deliveries and took off, rounding the corner on two wheels. My grandfather lies on his back on the couch, his head resting on a linen doily so the upholstery of the couch won’t get ruined. Doilies can be magically cleaned, but couches tend to resist the sorcery. The shirt of eight-year-old Cousinich has been replaced by a dishtowel, made from a converted flour sack, and the shirt is even now in the aluminum wash tub in the back. Someone rushes in with a block of ice wrapped in a dishtowel, and that’s taken to the sink, hacked at with a cleaver used for fish, a small chunk put back in another towel and given to my grandfather. The eye is examined, first by my great-grandmother, who humphs, an actual, old-fashioned humph, then by her sister-in-law. There is some blood, but not much. The fluid is from something else and mixed with tears, making it difficult to assess the full medical situation. The sclera is pink, and a line, a teeny laceration across the hemisphere, just inside the iris, is the telltale evidence. The bullseye. At first, it’s deemed a scratch, that the eye needs time to heal. We’ll keep it clean so it doesn’t get infected, my great-grandmother says, and by the time your father gets home, he won’t even notice. My great-grandfather is fishing for tuna off Ecuador. Hulls are still made exclusively of wood at this time. In the 1940s, my grandfather will own the first all-steel Purse Seiner. That was a much faster boat, but still he would be gone for three to six months at a time, depending on the offload location.

But my grandfather isn’t thinking about boats at the moment. He’s reliving the sound of the bounce on the tree. He doesn’t remember the actual piercing of the knife. The thud, then the sudden shock of recognizing a tremendously terrible thing has happened. The thud, the pressure, the flinging of the blade between his hands, and the holler of his cousin. It’s at this point that he registers that Beta Cousinich said shit and he wants to tell. But out of his right eye, he sees his mother, who still manages, despite concern, to look like Archduke Ferdinand ordering an execution, so instead he whimpers to solicit more sympathy. Now is the narrow window in which to milk any sympathy he will get. His hand is cold, and his entire head hurts, most of it now from ice-burn. My great-grandmother takes a turn holding the ice against his head, then calls for the other chunk melting away in the sink. Another sister-in-law brings the chunk and a refreshed towel, and during the exchange, at least four of them take turns assessing the progress toward recovery. The iris is turned outward, almost wall-eyed, and my great-grandmother asks what he can see. Nothing, he says, and his eye isn’t turning out, it’s deflating. My grandfather is allowed a thimble-full of homemade wine from the cask on the back service porch, his mother propping him by the neck so he can take a sip. He needs something stronger, the sister-in-law suggests, and a cheap bottle of sherry used for cooking is retrieved from the top shelf of the pantry. A doctor has not been called. Doctors charge money. Most are just Philistines or charlatans.

Late at night, when my grandpa got tired, was the only time I would remember which eye was actually fake. Unable to gauge how opened or closed it was, the lid would droop over the glass. Also, my grandpa was very direct in his glances and would look at you straight on during conversations. When tired, my grandpa would turn his head less, and his right eye would roll over toward you, but that left eye would just hang out in the middle. When his lid drooped, it almost looked as though the left eye was looking down, which was disconcerting. Things I didn’t notice before I actually learned he had a glass eye. I don’t remember him ever addressing the situation directly. I remember being very little and playing in the bathroom. My grandpa had a glass eyewash on his doily of necessities next to the sink, and I used it to experiment with mouthwash potions. I’m sure I cleaned it out after use, but then, maybe not enough after filling it with toothpaste and Listerine. I thought the eyewash was a mouthwash shotglass. Shit.

My great-grandfather's boat. My grandpa is the little one standing in front of the wheel house. My great-grandparents are standing on either side of him. This is still in Ballard. Agram is a town in Croatia; the boat was originally called Crikvenica, but everyone mispronounced the name, so he changed it.

Two days after the incident, the doctor who is finally called says if he’d come sooner, the eye could have been saved. The tissue, now raisined and grayish, must be scraped out. He wants to use a light dose of ether as a sedative. The bottle of sherry is retrieved again. The doctor uses a scalpel and tweezers. He charges $8.00. For the time, this is comparable to a few hundred dollars. For a Slav, this might as well be $10,000, and for a Slav, there’s no real difference between $10,000 and a million. My great-grandmother leans over the doctor’s shoulder, pointing out pieces for him to take.

Being young, my grandfather has plenty of time to adjust without the usual depth perception. If he had been born a generation or two later, he might have felt the loss of the 3-D movie experience, but he was a middle-aged father of two when that became a fad, and by then a commercial fisherman who didn’t see many movies, especially the extravagance of one in 3-D. He drove a car, he fished—net and longline. He played darts and ball with his boys when he was home, and he navigated with maps and math, not stars, on the open waters. He passed a driving test at the age of 90, although the distinction may have been questionable. A glass eye counts as 4-F for the draft board, so he never became a military man, not even after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. But even if he had double ocularity, my grandpa was not going to come up on any draft list. As a salty (and one-eyed) fisherman, he needed to pull anything out of the ocean that could be put into a can of K-rations.

As my grandfather lies on the couch while the doctor pulls out bits of matter, he begins to fantasize about hospital beds and stethoscopes and head mirrors, and women with loving caresses. He doesn’t have a specific idea about romantic love at this point. He will still love his mother, he decides, but there will be few things about her that make him feel sentimental. Possibly to compensate for the single eye, he adds an R to his last name. When he is twenty-eight, he will marry a woman known for her sweetness and saint-like patience whose only similarity to his mother is a shared cultural heritage. Their religion will shift from Catholicism to seeking out professional medical help. By the time all the Cousinichs are adults, the coven of mothers will have dissipated to hermetic widows who don’t go much farther than their front garden. The Cousinichs will have moved to different parts of San Pedro as it continues to expand west up the hill, and north toward Los Angeles. Neighborhood boundaries will no longer be divided by family names.

In the postwar years, beyond the necessity of K-rations, fishermen will suck everything out of the sea but the salt, and the fishing boats that run three-deep against the piers will diminish to two-deep, and within forty years, with a dozen or so exceptions, will disappear from the San Pedro Harbor. The wilderness, the strawberry and tomato patches long gone, the scene of my grandfather’s impalement, will become a strip mall. Changes such as these happen erratically, creeping up and then pouncing, or bouncing directly into your face. It doesn’t take two eyes to see this happen. Neither doctors nor witches can stop it. One-eyed fishermen adapt by becoming one-eyed longshoremen, and instead of inheriting a boat, my father will inherit a union card and the second R in his surname. He will never learn Croatian and will marry out of the diaspora. I will never experience the coven and will miss my grandfather desperately at times, but I have the satisfaction in knowing whenever I need to, I can look directly into his eye.

Jennifer Carr is a Los Angeles writer interested in the cross cultures of the working class, especially in the union town of San Pedro, where she grew up. She studied creative writing at USC, received her MFA from Chapman University, and currently teaches high school creative writing to future Pulitzer Prize winners at the Orange County School of the Arts in Santa Ana, California.