The Zapruder Siblings

An Interview by Dini Karasik

Michael

Matthew

Alexandra

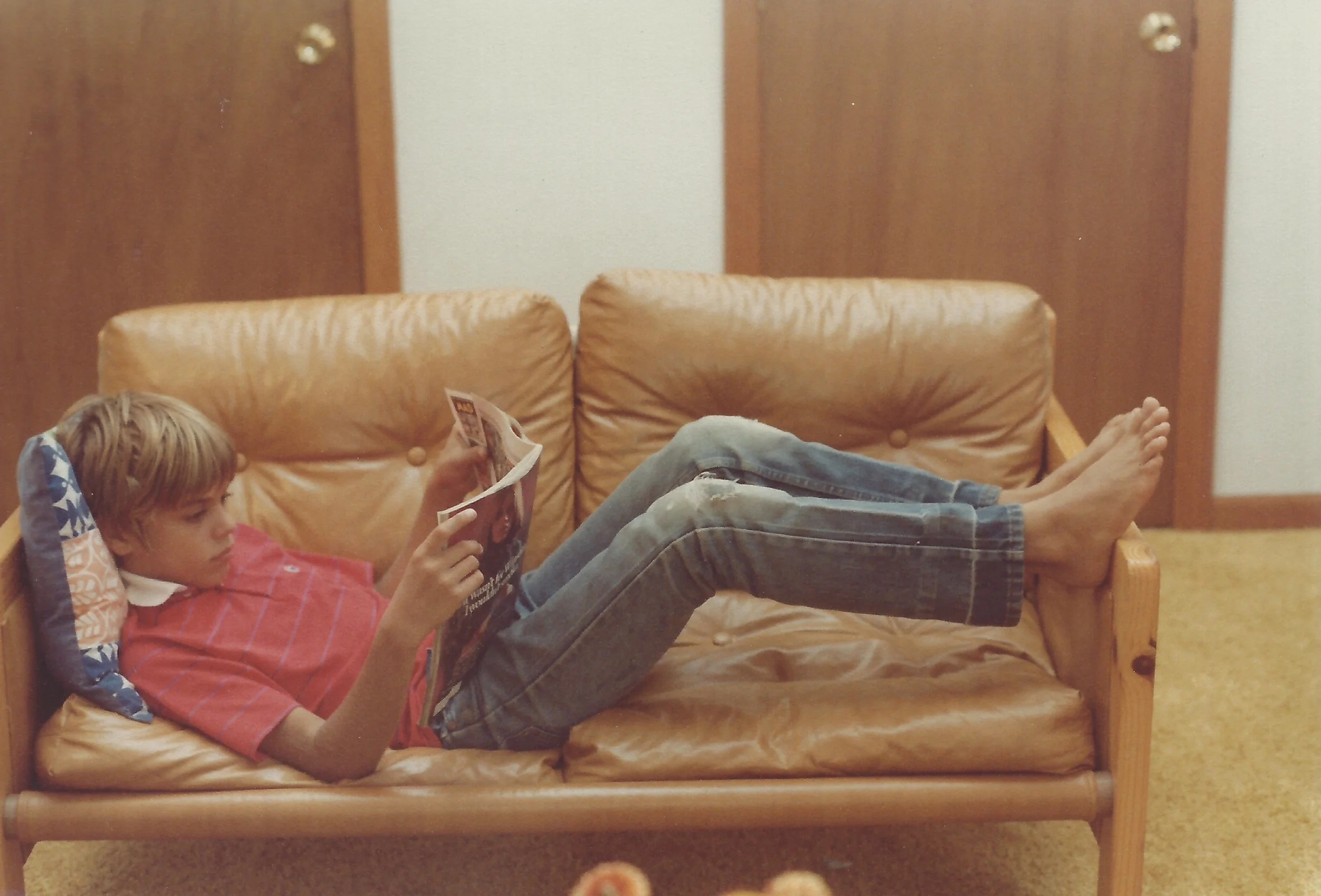

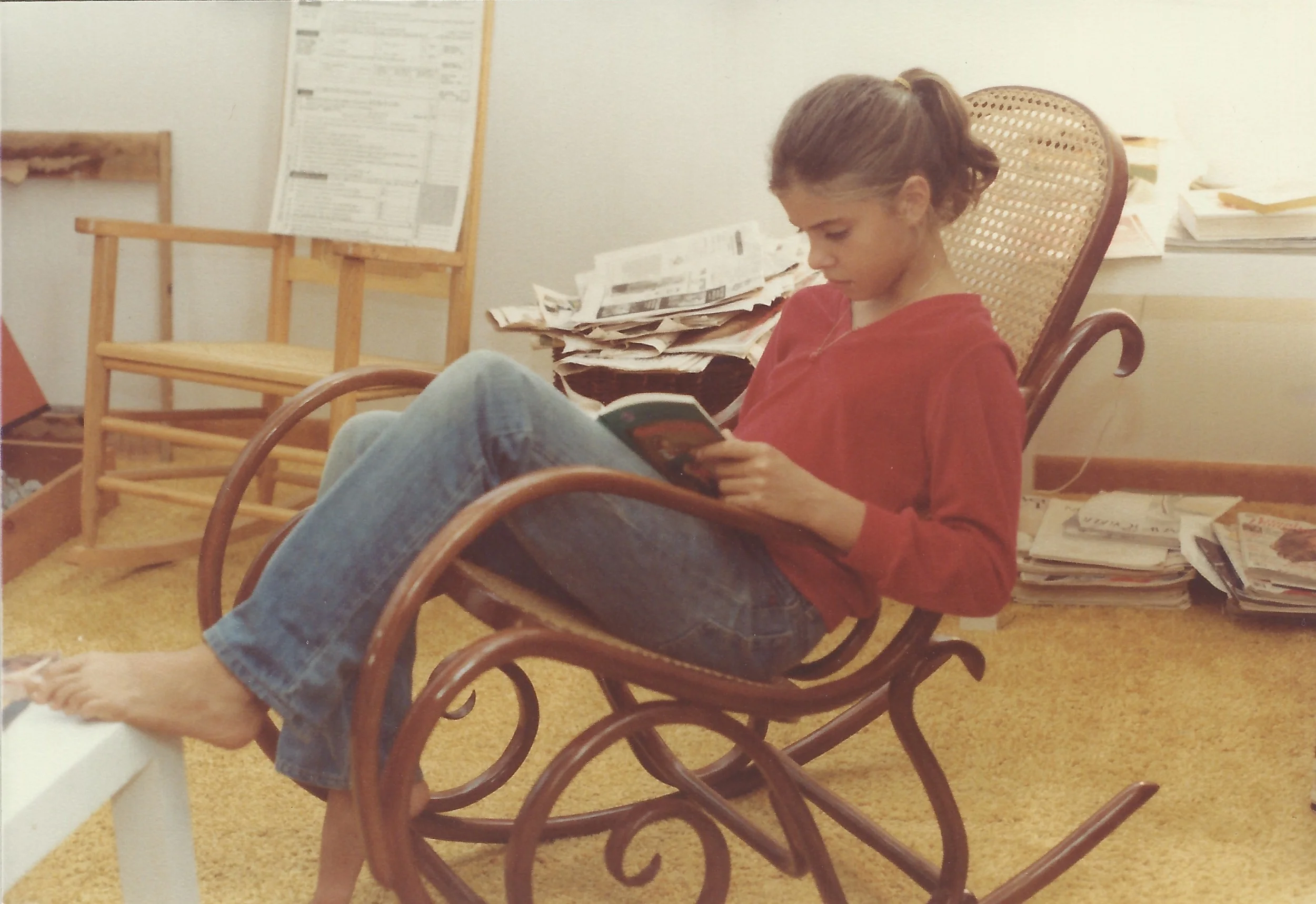

I’ve known the Zapruders for roughly thirty years. Matthew is the eldest; Michael and Alexandra are twins, two years his junior. They grew up in the suburbs of Washington, D.C. in an airy, sunlit colonial, full of original art, family photographs, and elegant yet comfortable furniture. Their home was a hub of activity—parties, dinners, holidays, always hosted by their warm and inviting parents, the guests more likely to congregate around the large kitchen island than to be seated in the formal dining room. In the back, a pool table and small television. When we were in high school, we spent a lot of time in that room but it mostly belonged to the boys. That’s where they watched football or played guitar, often with their father, Henry, whom they lost to cancer in 2006.

I moved to Maryland my junior year of high school. Alex was one of my first friends. In the years that followed, spending time with the Zapruder family was lounge-y and fun and full of spirited conversation. I had come from an unstable family background: a childhood spent in Houston and on the Texas-Mexico border; a couple of divorces; a mother with severe mental illness. I bounced around from family member to family member for several years. By the time I landed in upscale Chevy Chase to live with my father and step-mother, I’d changed high schools twice in three years. And while no family is without its dysfunction, for me, the Zapruder family exemplified love, togetherness, and stability.

Today, Matthew Zapruder is the critically-acclaimed author of four poetry collections, most recently Sun Bear (Copper Canyon, 2014) and Come on All You Ghosts (Copper Canyon, 2010)—a New York Times Notable Book of the Year. His work has also been anthologized in Best American Poetry 2009 and 2013, among others, and has also appeared in several publications, including Tin House, Paris Review, The New Republic, The New Yorker, McSweeney’s, and The Los Angeles Times. He is the recipient of a Lannan Foundation Residency Fellowship, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and a May Sarton Award from the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He also teaches poetry, is the co-founding editor of Wave Books, and has a forthcoming book of prose entitled Why Poetry, which will be published by Ecco Press in 2015.

Michael Zapruder is an award-winning composer, recording songwriter, and performer. He holds a Masters degree in music composition from California State University, East Bay, where he was awarded a Glenn Glasow Fellowship for excellence in composition. His portfolio includes works for solo instruments, voice and accompaniment, mixed chamber ensembles, wind ensemble, and electronic media. His substantial discography of original songs includes Dragon Chinese Cocktail Horoscope, which won the 2009 Independent Music Award for Best Songwriter Album; and Pink Thunder, an album of songs made from poems by living American poets, which was selected by the Boston Globe as the Best Poetry Book of 2012.

As a recording songwriter, he has a conceptual side: in 1999, as part of a project he called 52 Songs, Michael wrote, recorded and posted online one song each week for a year. More recently, he released the Pink Thunder songs as an interactive art show, with each song housed in one-of-a-kind music-playing art-objects called portmanteaus. The Pink Thunder in Portmanteaus art show has shown in San Francisco, Chicago, and Washington, DC. Michael is a co-founder of the San Francisco arts collective and record label, Howells Transmitter, and from 2003-2011, he established and led the curation group for internet radio service, Pandora. He is currently a Kent Kennan Fellow at the University of Texas at Austin’s Butler School of Music.

Alexandra is the author and editor of Salvaged Pages: Young Writers’ Diaries of the Holocaust, (Yale, 2002), which won the National Jewish Book Award in the Holocaust category. She wrote and co-produced I’m Still Here, a documentary film for young audiences based on her book, which aired on MTV in 2005 and was nominated for two Emmy awards. As a freelancer, she wrote Nazi Ideology and The Holocaust, (USHMM, 2005) and A Young Readers’ Biography of Anne Frank, (National Geographic, 2013). She wrote an introduction and edited the Diary of Rywka Lypcyc (Lerhaus Judaica, 2013) and contributed to The Day Kennedy Died (Life Books, 2013). She is currently completing a digital edition of Salvaged Pages with extensive new content and a related curriculum for teachers in history, literature, and writing. Her latest work, Twenty-six Seconds: A Personal History of the Zapruder Film (Twelve Books) will be published in November 2016.

Here, my three gifted and talented friends discuss the aspects of family life that laid a foundation for their respective careers as writers, musicians, and artists.

ORIGINS

The fact that you’ve each "followed your passion” and enjoyed success is remarkable. You didn’t find your writer/creative selves after a ten-year law career, for example. It seems as though you were on the path from a young age. What do you make of your respective trajectories? Is it nature? Nurture? Good nutrition?

MATTHEW

As the eldest, I will, as usual, barge in and answer first, then wait to be corrected. I think, in my case, it actually did take me a long time to find myself as a writer. We didn't grow up in a family that particularly encouraged artistic expression as a main focus or "career," though there was a lot of music in our house and appreciation for culture. Art was highly respected, but more as something to experience rather than as something to do. Which, actually, is totally ok, at least with me.

To my recollection there was much more talking about politics and current events. We did travel a lot, around the U.S. and a couple of times to Europe, particularly France, which my parents both loved. Our parents were curious people, who loved other cultures, and who were open to meeting new people, trying new things, seeing different cities and eating and drinking and hanging out. Our house was often full of friends—both from the U.S. and abroad—cooking and drinking. I think one of the most important things I got growing up was this idea that just going out and seeing what's happening in the world is in and of itself a good thing, especially when one is a participant and a friend, not just a tourist.

Growing up there were a lot of other things being talked about rather than art itself. I feel connected to all sorts of other interests. And when I did come eventually to writing, particularly poetry, it felt like my own thing. As I said, music was a big part of our family life, both playing it and listening to it. Visual art is something I have been thinking about for a long time, and now, later in my life, after my mom went back to work at the Museum of American Art at the Smithsonian (a job she had had before I was born), I see that her interest in that must have been something I absorbed unconsciously as a youngster.

ALEXANDRA

It seems totally natural for the three of us to be engaged in creative work around words and music and ideas. I can’t imagine any of us as a doctor or lawyer, for example, or really doing anything other than what we are doing. On the other hand, I know that it wasn’t a straight or easy path for any of us, and I agree with Matthew that our parents—as much as they valued art and culture—were more about appreciating it or doing it as a hobby (our dad loved to cook and make watercolors, and our mom is an amateur photographer) than making it a career.

I definitely remember family dinners and talk of politics, like Matthew does. And I, too, remember a lot of cultural exposure as a child. My mother and I had season tickets to the ballet where we sat in the second to last row of the top balcony in the Kennedy Center Opera House in front of this nutty, friendly lady named Chloe who always brought me a big bag of candy to eat during the performance. In addition, our parents always took all three of us to concerts and musicals and plays. There were always books all over the house and they read a lot. Our dad loved history and books about the natural world, science, and Albert Einstein, and our mom read magazines, especially The New Yorker and Gourmet, every single issue of which is, I believe, still up in our attic.

It may sound a little too deterministic, but I feel like there was always a deep appreciation for words and language in our house. There was a high value placed on ideas and conversation and argument, though my dad loved to argue and my mother hated it. I learned how to articulate my ideas and defend them, and even though the discussions sometimes ended with people getting mad at each other, there was also a lot of laughing, and people poking fun at each other, usually in a pretty loving way but not always.

In terms of finding a path, it took many years and a considerable amount of struggle to finish my first book and many years after that to think of myself as a writer. I started writing essays and little meditations when I was pretty young, probably in 4th grade or so. I wrote a diary which turned into a journal that I kept all the way through college. Writing was definitely a way for me to organize my thoughts and feelings.

When I went to college, I found that I also had my own ideas about art and literature, and that expressing those ideas in writing came naturally to me. But throughout my twenties, I vacillated between being an educator in museums or in the classroom, and pursuing a project that had come out of my first job at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum to research and collect young writers' diaries and publish a book about them. Being an educator seemed like an obvious choice; I had always been drawn to teaching and kids and museums and art. And, unlike writing a book, it was a real career for which one might earn a regular paycheck, and it was the choice my parents decidedly preferred for me. So throughout my twenties and early thirties, I had a professional life that revolved around these elements: first in exhibitions and education for young visitors at the Holocaust Museum, and then when I earned my Master's Degree at Harvard in Education, and then, later, at the Corcoran Gallery of Art. But all the while, I couldn't let go of this project to write my book, even though it was daunting and complicated, and the subject matter was dark and difficult and scary, and it made me very emotionally vulnerable for a long time. It didn't help that my parents were worried about me and that I was anxious and depressed. But I felt that this was what I had to do and that it was worthwhile and meaningful and important for me. Intuitively, I felt that I didn't want to be a small part of a big institution, or a teacher in a classroom with kids passing through. I wanted to say something new in writing, about something that I cared about, and I just couldn't let that go.

MICHAEL

Like Matthew and Alex said, we grew up with music and art and culture in the picture, but the most important thing was always doing well in school. To a lesser extent, we were expected to have a kind of verbal acuity in talking about things like politics and such. In terms of our immediate experience of creativity at home, our father played folk songs on the guitar, especially when we were young, often right when he got home from work. Musically, he was an amateur in the purest sense of the word, and did not have any professional or public ambitions. I think we all encountered a kind of pure, simple, intrinsic creative satisfaction in his playing. That made a big impression on me, certainly. Even with his modest technical abilities, he really could get the essence of a song across.

The serious arts were there, too, but at a remove. If our childhood home was a village in the Serengeti, the arts were the lions, snakes, rhinos, and all the other dangerous but awesome charismatic megafauna that were out there. While our parents admired the arts, and while the arts in some ways formed the basic shape of our lives, I think they also threatened something basic in our parents' plans for us. We knew to keep a certain distance.

As for social parlor skills, since I’m not ideally suited to the kind of verbal scrums that happened so often in our house, I spent almost the entirety of my family's many hours of group discussion daydreaming. I rarely spoke up, and when I did it was usually just to say something provocative or more often, incomprehensible. To this day, I have a kind of instinctive feeling that I should have something interesting to say about Lawrence Eagleburger or the S.A.L.T. II talks.

Our grandparents played music, our mother studied art history and worked at the Smithsonian, our father played guitar and loved songs, and both of those generations worked hard to establish our family in America and to give us the opportunities we have had. I think, on some level, I probably felt inappropriately special (I was accomplishing a lot in my daydreams), and on another, archaic as it may sound, I wanted to live up to the sacrifices of my parents’ and grandparents’ generations. There’s a story that one of our grandfathers used the first paycheck he ever got to buy a violin (an instrument that I now have). Somehow, I have a feeling we were meant to be doing these kinds of things.

ORIGINS

Michael, you’re a self-taught musician.

MICHAEL

Up to a point, yes. I was originally self-taught as a guitar player, and then in my twenties I learned music theory, which prepared me to play piano in a rudimentary way. I had been a lead guitarist and had also done a huge songwriting project called 52 Songs, for which I wrote, recorded and posted a song online every week for the year 1999, and I just needed something new so I started writing songs on the piano. I taught myself up to a point, but I take piano lessons now.

ORIGINS

What drives each of you to create or learn something new?

MICHAEL

As my three year old often says: “I just need to.” I don’t think I can break it down too much, but this question always reminds me of that scene in the great Julian Schnabel film Before Night Falls in which Javier Bardem’s character is asked: “Why do you write?” He answers: “Revenge.” I would say: "To answer." I can’t really explain why, but I just feel that, for me, the experience of living merits a response of some kind.

In terms of learning new things, I just find life very fascinating. Also, I wasn’t much of a student until I went to college, and like many formerly bad students, I’ve grown up to be an autodidact. You might say that I’m blessed with a persistent awareness of how much more there is to know.

MATTHEW

I did happen to be a kind of typically older brother-ish, overly diligent student, so for me learning and creating are, in a way, a movement away from accepted categories of inquiry. I like to define my own way of thinking through things, which is really what poems are. I am mostly searching for exciting and inexplicably resonant language and ideas when I read or study things that might eventually make their way into poems, moving upward from the subconscious, magically, at just the moment when they are necessary in the course of writing the poem.

ALEXANDRA

I am always, unconsciously, I think, seeking patterns and rhythms in the world. I want to find the shape—probably in a more analytical way than either Michael or Matthew—of events in history or relationships between people and the past, or whatever the subject might be. I think I want to find the story that explains how and why things happen the way they do, the interplay of people and actions and thoughts and beliefs and ideas that make up a narrative.

For me, the most exciting thing is to roam around in a lot of bits and pieces of information (whether that is historical documentation or ephemera, or whether it’s different people’s accounts of the same events) and wait for the order to emerge. Or I look for the flash of a thought that begins to suggest how a lot of seemingly random and unrelated historical bits in fact form a coherent account. This is also about a deep conviction in the absolute truth of the past—a truth that so often eludes us in the certainty of our present day perspective—and how it is suggested when we dig around in the stuff that the past has left behind.

In college, I fell in love with the study of ancient Rome and Pompeii. I loved the idea of fragments. I loved to look at an image of the ruins of an ancient temple and see in my imagination all that was no longer there, all that was real to the people who belonged in that era. While it is only a ruin to us, it was once a living, vibrant temple filled with people and their gods. That past is true, just as our present experience of it is also true. This kind of historical inquiry is not about comfortably inhabiting a present-day point of view and imposing an order on the “story” of the past. It’s about layering imagination, knowledge, and perspective in order to uncover a story that is not only historically accurate but that feels deeply true in the most human sense. As an aside, this is why I don’t feel limited to only writing history. I have my own set of big questions that I want to explore, and they may take any form. I am interested in writing fiction and I have ideas for more journalistic projects about present-day topics.

ORIGINS

Is collaboration with other artists and each other important? Can you talk about Pink Thunder and how that came about? And what are your thoughts on poetry and song lyrics?

MICHAEL

Pink Thunder was the intersection of a few things for me, but it really wasn’t as directly collaborative as it might appear. I was feeling a strong need to do something ambitious and very different from the songs I heard every day, which all seemed to be so fundamentally similar not just in their form (verse chorus verse chorus bridge chorus, etc.) but, even more importantly, in their purpose. I like what poems do, and I wanted to sing poems as songs to see what happened, and especially to see if the songs could do the same kind of things that the poems did. So, I basically took poems back to my studio and turned them into songs. I didn’t even tell the poets about the songs until they were fully written.

That said, in terms of collaboration, my conversations about music and writing with Matthew and Alex over many years have been incredibly important and inform everything I do.

As for poetry and lyrics…in my opinion they are not the same thing, at all, although I think Pink Thunder proves that well-written poems, if left unchanged, can serve as the backbone of a certain kind of song. Maybe I should say that, while people (erroneously, I think) always call their favorite songwriters poets, it seems to me poems really can be accurately categorized as a kind of song. If they are songs, they exist at the extreme end of the continuum, where the music is silence and the melody and rhythm are compressed into the subtle cadences of speech. Song lyrics, on the other hand, are in the center of the continuum. Combining words and music, the words are often the tip of the iceberg and the music is the rest of it. Among other things, I think that writing lyrics is therefore a game of knowing how much the music is already saying, and not being redundant with the words.

MATTHEW

As Michael writes, Pink Thunder wasn't really a collaboration: that project is all Michael's work, on top of the work that had already been done. I was absolutely blown away by what he did. It seemed like something completely new to me. Many wonderful composers have done excellent classical, or contemporary classical, adaptations of poems; there's a long tradition of lieder, etc., which Michael knows far more about than I. I've been lucky enough to have some of my poems set to music in wonderful compositions by Missy Mazzoli and Gabe Kahane. But most popular song adaptations of poems are, in a word, disastrous. Pink Thunder might be the exception that proves the rule in the sense that the project points to the strengths and limits of popular song as a vehicle for poetry; it adopts and adapts and moves organically as close to or as far away from traditional pop structures as necessary to create a new musical piece out of each poem.

Collaboration is fascinating to me, I've done it in various ways with some people, though nothing too serious. I think of it mostly as play. In a way, collaboration can be seen as much as a means of developing and deepening a relationship between two people. I think my relationships with my two siblings are pretty deep and rich already, which might explain why we don't necessarily feel driven to collaborate. And I would agree with Michael that my conversations with each of my siblings have helped me think through ideas in my own work, and hopefully vice versa.

ORIGINS

Alex, I see your work as a little more solitary. Do you agree? With Salvaged Pages, your partners and collaborators were the young writers who lived during the Holocaust and whose diaries you read, compiled, and edited. The book you’ve just written about your grandfather, Abraham Zapruder, and the Zapruder Film is also a sort of history project. You’ve had to do research, cull through historical records, interview witnesses, and mine your family’s photos and personal papers. What does collaboration look like in this context?

ALEXANDRA

My work is definitely solitary in the sense that I need to digest a great deal of information and let it percolate until the narrative begins to emerge. But I don’t think this aspect of it is different in a fundamental way than what Michael and Matthew do. And in some ways, I’ve adapted my methods of research to suit my extroverted nature. I am constantly corresponding with and interviewing people, and making contact with historians, librarians, archivists, and others to try to get the piece of the puzzle that they can provide. It’s true that there is a lot of reading and a lot of culling through primary sources, which is my favorite part. But I also talk to friends and colleagues about my ideas and that process helps anchor the ideas in my head. In some ways, I’m really the antithesis of a writer because, while I am perfectly happy being alone, I am not at all an introvert. I am interested in people, and I can find it difficult to be still and quiet enough to do the laborious work of note taking, outlining, and even writing, though I do genuinely love to write.

ORIGINS

How do you experience each other’s work? You may have insight into a story, image in a song, or line in a poem that the average consumer of your work won't have. But are there any drawbacks to knowing each other so well when it comes to art?

MICHAEL

I love and admire my siblings’ work. I do often have a pretty exact idea of what Matthew is referring to in his poems. It’s not different in kind from the way anyone else would fill in the descriptions in a poem with their own images, but in my case, I think there are times when I’m filling in that ambiguity with the same exact down jacket, bike, or amplifier that Matthew was thinking of, which is cool. In Alex’s writing, I can see certain very familiar ways of thinking about things, always expressed in her remarkable, musical language.

MATTHEW

There aren't any drawbacks for me. Often I will have a highly emotional reaction to Michael and Alex's writing, for precisely the reason Michael points to above. Because they are both great writers, reading them is like being with them. I suspect that's why people like their writing, but for me it's, of course, a different experience. I also think I have gotten to know each of them through their work in a way I would not have otherwise. The fact that we are all writers of various kinds has, luckily, even further deepened our connections. Plus, it's nice to have siblings who understand the ups and downs of writing and making. There's a whole lot of explaining we don't have to do to each other, and a lot of natural sympathy, beyond the familial.

ALEXANDRA

At the risk of being repetitive, I have to say that I love my brothers’ work. I am constantly amazed and inspired not only by their creativity but also by their incredibly hard, persistent, diligent work. I think I experience Michael and Matthew’s work in a similar way to what they each describe. If there is a drawback, it is only that it can be very emotional, and sometimes it feels like they are literally putting their fingers into my heart, which can hurt.

Whether it’s what they intended or not, I read and hear their work through the lens of a shared life experience, and often it is obvious to me what the points of reference are. In some ways, this is a way of connecting deeply to them, and it’s very personal to me. But I realize that my experience of the work is neither that of the artist nor that of the intended audience, which can be a little lonely. By that I mean, I feel it so deeply and no one can share it with me. Trying to tell someone doesn’t work. I just have to experience it, which sometimes feels like being awash in feelings, memories, pathos, or joy. This exists throughout their work, but when Michael released New Ways of Letting Go, and when Matthew published Come On All You Ghosts, it was almost excruciating to hear how they evoked—in words and music—moments of our dad’s illness and death. My narrative of that experience was bound by prose conventions that failed to work for me. It was bigger than that. Instead, I find moments in Michael and Matthew’s work that tell me the story of my own experience in a way that I could not tell it to myself—utterly true and therefore painful and comforting at the same time.

This experience isn’t limited to their work that touches on our childhood or our dad’s death. Just as one example, (and I can find many across Matthew’s poems and Michael’s music), Michael wrote a song called On the Arm of a Burning City which tells a story set in the Spanish Inquisition. In the lines of that song, and its mournful, hollow, echoing melody, he captured, I think, more fully and completely the pathos of Jewish expulsion and genocide than almost anything I’ve ever read. Every line is so totally true. And the music amplifies the lyrics, making the truth of it that much more inescapable. These lines always stand out for me:

Here, all of your important books would be

sewn into sumptuous leather and gold,

stacked up, waiting to leave on the evening trains.

How many now wish they could send someone,

safe, bound up in some other skin, to the

warm lamplight that graces those places of study.

You can find this song on iTunes and you really have to hear it to understand what I mean. But for me, the song says everything I could have wanted to say in my book about the Holocaust.

On a more prosaic note, I really do agree with Matthew that having two brothers who are devoted to creative work is just comforting. We can talk not only about the big ideas, but also about publishing, agents, contracts, disappointments, choices, and all the challenges of the business of producing creative work. Also, Michael and Matthew have been unfailingly supportive of what I want to write. More than anyone else, they always see the value in it, trust me to do it well, and challenge me in really meaningful and important ways to be smarter and do better. Matthew was very helpful with Salvaged Pages when I was wrestling with the introduction, which was very difficult to write, and he immediately saw the problems and articulated them in a way that I could hear without feeling defensive. That piece is perhaps the one I’m most proud of so far, and that’s largely because Matthew helped me get to the essence of it. Now, with the Zapruder film book, which not everyone in the family embraced at first, they were there to push me to think about why to do this, how to do it, and how to make it really interesting and meaningful. This is a project with inherent risks; because of the public interest in the story, there can be pressure to follow certain conventions of commercial non-fiction and memoirs. I know that Michael and Matthew have my back. They encourage me to think creatively, seriously, and deeply about what I am doing, and they are always there to talk to and help me grapple with the complexities of the story I want to tell.

ORIGINS

What are you each working on these days?

MATTHEW

Right now I am finishing up a prose book, Why Poetry. It's about the misconceptions people have about poetry that interfere with the reading of it, as well as an argument for poetry, both as a genre and as a useful thing in the world. It's for general readers as well as specialists. I've been working on the book for several years, reading and writing about poetry. It turns out writing prose is hard! Who knew? Anyway that has been taking up most of my time.

Other than that, I have been scribbling a little bit of poetry, just starting to think about the next poems. I was lucky enough to teach up at the Squaw Valley Writers Workshop this summer, where everyone, including faculty, writes a brand new poem each day and brings it into class the next day. It was difficult and interesting. My first few poems were quite atrocious and embarrassing but by the end of the week I was starting to feel it, a little bit. For me it's like exercising, after a long layoff it takes weeks to start feeling right again.

Finally, I'm also getting ready for next year, teaching at St. Mary's College of California, in the MFA. I'm teaching in the fall, about finding ways to write poetry in one's daily life. We will be reading poets who engaged with dailiness in various ways, as a method and/or subject, thinking a lot about form, process, the subject matter of daily life, and so on. We'll also be taking on a daily creative task related to poetry, so in some way writing every day during the semester, which I think is something poets need to at least try at some point. These are all tasks and subjects that interest me greatly, not just as a teacher but as a poet as well. They are very bright and dedicated, and it's a great program.

MICHAEL

I just finished getting my M.A. in (music) composition, so I’m composing a lot and exploring new opportunities that are extensions of the things I learned getting that degree. There is a release date pencilled in next year for another set of Pink Thunder-like songs, as well, so I will be hard at work on that in the coming year. I’ll be writing a new set of songs, recording them, and I also want to score the songs for chamber orchestra and voices. For about four years now I have been slowly working on another record of my own songs. That will be finished and released sometime in the next year. And finally, for the first time in a long time, I’m feeling some interest in writing some new songs. I have an idea for that which I’m kind of incubating.

ALEXANDRA

I’m working on one pressing project and one long-term one. The current project is a new, revised version of Salvaged Pages: Young Writers’ Diaries of the Holocaust, which came out in 2002. I’m lightly revising it and it will be re-issued in a new paperback edition, and I am working with a pretty big team of people on an e-book version which will have extensive new content in the form of glossary terms, maps, historical and personal photos, images of diary pages, artifacts and documents, and interviews with Holocaust survivors. The main goal of the e-book is to make the content of the book available in a new form for teachers and students around the country. It has been an exceptionally complicated project, not only because the form is relatively new, but because there is so much content to manage. I have also worked with a gifted team of educators on a very comprehensive curriculum to bring out the historical, literary, and writing potential of these diaries for classroom teachers.

My new book, which I plan to return to working on in September, is a history of our grandfather’s home movie of President Kennedy’s assassination, known to many as the Zapruder film. It’s in part about our grandfather and our family, and in part about the life of the film and the way it shaped aspects of American history and culture. During its five decades, the film has, of course, remained exactly the same as the day on which it was created, while absolutely everything around it has changed. In this way, its history involves the media, technology, law, JFK assassination theory, public notions about privacy and access to information, film, the arts, and popular culture. I can’t say that I know what the outcome of this book will be. I believe that there are many different threads that I have to weave together—public and private, collective and personal, moral, legal, artistic, and on and on—and that will be the project of the work. My aim is to tell the story, and to hopefully illuminate these themes and threads as I go. In some ways, it is also about the way that our father, and our family culture, influenced the life of the film, which in turn had a meaningful effect on certain aspects of American culture, and how the film itself influenced us, or at least me. The personal side of this will be by far the most difficult part for me. But I’m going to try to create something that is both narrative non-fiction and personal history or family memoir, because the two threads are intertwined and there is no full story of one without the other.

ORIGINS

What really jumps out at me in this interview is how empathetic you three are—with each other but also with respect to your parents, grandparents, etc. Talk about the role of empathy in poetry, music, storytelling.

MATTHEW

I’m very interested in this word empathy. I don't think it's something I think consciously about when I'm working on poems. It's too conceptual. But I did think about this off and on when I was writing my most recent book, because I actually do think empathy is related to the basic nature of language. Language in a way can be seen as a version of empathy. The challenge of empathy is to find a way to cross over from our own personal selves and internal worlds into some other space, an identification with, or understanding of, another being (or maybe even something inanimate!). That's the challenge and miracle of language too, that it is able to be both private and common to others. Empathy, language, poetry, these things are about where my world comes into contact with yours, in a way that is not violent but loving.

The question of empathy is central to much literature today. Right now I'm reading Sheila Heti's tremendous novel How Should a Person Be, probably the best book I've read by a contemporary author in years. The entire book, in a way, is about empathy—toward friends, toward oneself—and about how to live in an unjust world. These are the questions that face us all, and if we are awake, we are struggling with them in our own ways. Probably there are no solutions, but on the other hand, there are surely better and worse ways to treat each other.

MICHAEL

I’m not sure I can add anything to Matthew’s typically insightful and interesting comments. I agree with his description of the challenge of balancing the internal and the empathetic. That said, I don’t have much to say about empathy as it relates to my working process, except to say that I always try to empathize with whomever is going to be listening to the music I’m making! I do believe in honoring the time and attention that other people give to something I’ve made.

For me, making a piece of music that works is difficult, and adding empathy or any other secondary goal to the effort has never led me to make anything good. Maybe some people can do that, but I can’t. At this point I just want to encounter the actual music I’m making, to hear it just as it is, and to make it what it needs to be. In that kind of music, I think the resulting artistic truth (whatever that term means and whatever form it takes) will contain within it an ineffable goodness that somehow encompasses and even surpasses empathy and everything else. I think this is especially true of instrumental music, since it manages to speak and communicate without or above and below language.

ALEXANDRA

In Salvaged Pages, the problem of empathy was a very real one, and it's probably so in a lot of narrative non-fiction. I needed empathy to get enough inside the experience of the writers in my book to be able to convey that which was important, without being so close that I was crippled by the pathos of their situations. I clearly remember that there was a time when I was so much inside the material that I couldn't function—not only in terms of work, but in a lot of areas in my life. I couldn't find the bottom of the horror and the suffering and that made it impossible to produce anything. People I worked with told me that they grew hardened to the stories of the Holocaust and that seemed like an even worse alternative. I knew I couldn't write the book from that place, either. Eventually, I felt that I reached a sort of "detente" with the material. I located the place for me where I could love the diaries and their writers (whatever that means when describing people you don't know) and thereby convey that in writing without getting so close or so involved that it risked engulfing me. It may sound melodramatic, but that really is how it felt to me then.

To some extent, this is probably a balance that nonfiction writers need to strike each time they write, and it's probably a different distance depending on what one is writing. I am certainly thinking about this already with the Zapruder film book, and this is a particular problem when writing something that has an aspect of memoir or family history to it. It's not only that I genuinely empathize with my grandfather and father—this doesn't require any work to accomplish—but also that I want to honor their memories and I feel a strong sense of loyalty to both of them. At the same time, a book can't be a paean to the people you love without being one-sided and possibly boring or inauthentic. So, I need to find empathy and understanding for all the people who were players in the story of the film's history, even when their actions—and their hostility to our family and misrepresentation of the truth—is deeply hurtful and offensive to me.

Ultimately, writing stories is, for me, about trying to understand or make sense of some aspect of the world, to put order and 55

shape to something. And since it's the actions of people that usually [results in] stories, it follows that understanding people would be required to tell the stories well. I am curious about why people do what they do, and I am like my dad, I think, in that I find it hard to believe or accept that people are just evil or hateful or uncaring or cruel for no reason. There is definitely a bit of naïveté in that but if it doesn't always help in life, it definitely helps as a writer.