An Interview by Jennifer Maritza McCauley

Michele Jessica Fièvre is a master of multi-genre literary work. Born in Port-au-Prince, Fièvre self-published her first mystery novel at sixteen, signed her first book contract at nineteen for a Young Adult novel, and she has written children’s books, short stories, plays and poetry in French and English.

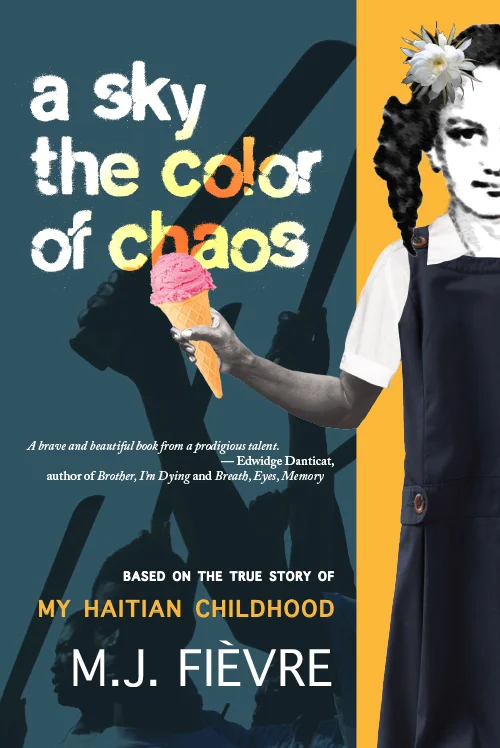

Recently, Fièvre debuted A Sky the Color of Chaos (Beating Windward Press, 2015), a fearless memoir recounting her childhood in Haiti. Fièvre also is the editor of the popular literary journal Sliver of Stone, and she has taught workshops in Miami and has edited numerous anthologies. Fièvre pursues and excels at so many genres and projects because she is devoted to her craft and is excited that “…there are some many stories to tell, and so little time.”

Here we discuss the Haitian literary community, writing in different genres, and turning real-life into memoir, among other topics.

ORIGINS

You're a beloved author in Haiti and in the United States. You became a big name in Haitian literature at a young age and your work is similarly well-received in the United States. What do you enjoy most about the literary community in Haiti? In Miami?

FIÈVRE

When I published my first novel, at 16, I’m not sure there was a literary community in Haiti per se. Not an established one anyway. I’m sure there existed friendships among writers, along with private writing circles (somehow I imagine serious writers gathered on a veranda among birds of paradise and begonias, eating slices of mango and drinking sugary aperitifs), but most of the Haitian writers I met seemed to work in isolation. When we did gather for book events, I felt like an outsider. I was too young, I guess, to be taken seriously—I had much to learn, much to prove. It didn’t help that I danced to the beat of my own drum. I remember the journalist who, at a panel, gave me long, disapproving stares, disgruntled by my decision to stay away from a “littérature engagée” (a literature that makes some kind of statement about Haitian society and politics) and tell, instead, tales of horror and fantasy. Writer Georges Anglade stood up for me that day: “She defies expectations,” he said. “Isn’t it what writing is supposed to be about?” For that reason, I’ll always remember Georges, who passed away during the 2010 earthquake.

Later, after I left Haiti, I became a writer of the Diaspora—I was, again, “other.” I’m still not trying to fit in: I belong in the margins because I refuse to be labeled, to let literary trends guide my writing. In Miami, my readers are my community—mostly teenagers with lots of angst and unabashed love for my work.

I deeply love the literary community in Miami. I’m part of various circles, and there’s real camaraderie among writers. I’ve been involved with the Miami Poetry Collective for a while. I’ve participated in various events and workshops put together by O, Miami and Reading Queer. I’ve had a play performed at MicroTheater and I’ve been a writer-in-residence at The Betsy. Every year, I look forward to the O, Miami Poetry Festival, the Anancy Festival, the Haitian Caribbean Festival, and many others. In Haiti, there’s always something literary to do; there’s always something to learn. I love it here.

ORIGINS

Your newest memoir A Sky the Color of Chaos explores your childhood during the reign of Haiti’s President-Priest. Would you talk a bit about why you decided to write a memoir about your childhood specifically? Why did this time of your life inspire a memoir? Why did you decide to write the book now? Were you worried at all about writing about the real-life characters in your book?

FIÈVRE

I didn’t set out to write a memoir. Growing up, I mostly read fiction. The stranger the tale, the more appealing, as I needed a reprieve from the realities of my life—the violence, not only at home, but in the country as a whole. I also watched a lot of television, mostly Japanese anime in French, but also American programs. Because of shows like 7th Heaven or The Cosby Show, which portray functional families in relatively balanced environments, I understood that my life, both as a Haitian citizen and the daughter of an irascible man, was not the norm. A normal childhood shouldn’t include protests, shootings, lootings, and home invasions (not isolated incidences in Haiti, but rather usual occurrences). A normal childhood shouldn’t include emotional and physical abuse, and night terrors.

At 16, when I began my writing career in Haiti and the other French Antilles, I embraced horror as my genre. I didn’t want to write about reality. Why would I? I was just a kid and, as I explain in A Sky the Color of Chaos, I barely understood people and politics. I also didn’t want to dwell on my fears and insecurities. In retrospect, however, I see that my fantastical tales foreshadowed my interest in nonfiction as I usually established a link between my stories and the political/social atmosphere in Haiti.

At the time, even in my diary I didn’t open up. In my entries, I used humor to ponder the comical and cynical in my life, for my sister’s entertainment. I did attempt, once or twice, to bare my inner struggles. The result was disgust with the self: Why couldn’t I just get over the pain? Why was I so weak? I was angry. After all, I was lucky on so many levels: I had food on the table, when so many in Port-au-Prince were dying of starvation. My father, although emotionally volatile, remained a good provider. I felt fear and confusion, and I didn’t think that my story mattered. Nonfiction writing required courage. Only years later would I encounter one of Nelson Mandela’s most famous quotes: “I learned that courage was not the absence of fear, but the triumph over it. The brave man is not he who does not feel afraid, but he who conquers that fear.”

As a graduate student in the Creative Writing program at Florida International University, I took a memoir class with Dan Wakefield. I read Alison Smith’s Name All the Animals. It was my first encounter with memoir, and I was struck. The writing—so beautiful! The lack of self-pity—inspiring! I learned the most important lesson from this writer: “The [reader’s] full experience comes when [the writer doesn’t] shorthand, sentimentalize or use clichés.” (Interview for Gulfstream Magazine.) As a requirement for the class, I shared nonfiction pieces in workshops. The reaction of both my professor and classmates took me aback: they were interested. I discovered I had a story to tell. My childhood had been more unusual than I thought. All the short pieces I wrote at the time, starting in 2006, would later become A Sky the Color of Chaos. Nine years. That’s how long it took to tell my truth.

While working on the first drafts, I didn’t pause to think about how the people I talked about would react to the writing. After all, to quote Anne Lamott, “You own everything that happened to you. Tell your stories. If people wanted you to write warmly about them, they should have behaved better.” Besides, I never thought that the parts of A Sky the Color of Chaos would ultimately become a whole and get published.

When writing, I enter another realm, withdrawing myself from reality. With nonfiction, my “characters” are still very real, of course; yet, on some level, they remain mirages—fragmented recreation of the individuals I write about, so that, even with memoir, it’s easy to dissociate from reality and underestimate the impact that the stories might have on the people in my life. One day, I introduced my Aunt G to Professor Wakefield. “I feel I know you,” he said. “I read about you.” Aunt G’s face fell and only then did the creative realm and my reality collided. I struggled with the question: how far should I go to protect my family’s privacy? In the end, I decided to change all names. I also requested that my publisher add the wording, “based on a true story,” which entitled my family to remove themselves from the tale, if they chose to do so. I combined all my sisters into one, to protect them. Nonfiction purists will undoubtedly frown at those “liberties,” I know, but my family’s sensibilities matter to me. In an interview for Sliver of Stone Magazine, Susan Orlean said, “A story can be extremely subjective and still be true. Your obligation as a writer is to indicate very plainly where the subjectivity comes from.” I think the “based on” wording helps maintain the contract with the reader.

ORIGINS

Edwidge Danticat has said your book "…is a heartfelt and deeply honest coming of age memoir that examines [your] family as well as [your] country.” While you were writing the memoir, did you think about its impact on Haitians, Haitian Americans and non-Haitian readers or were you focused more on telling your own story? Did you see Haiti any differently after finishing the book?

FIÈVRE

At first, I mostly wrote for myself and for a small, diverse audience of eight to twelve graduate students in a creative writing workshop at FIU. I was the only writer of Haitian descent in the group, so there was no one, really, to challenge some of my assertions. During later stages, I shared my work with my non-FIU critique group, composed exclusively of Haitian and Haitian-American writers. Thinking about these different audiences kept me grounded. My non-Haitian readers were more easily impressed; they showed amazement for details I didn’t even realize mattered (“What do you mean you didn’t have running water?”). Everything was new and strange to them. On the other hand, for my Haitian and American-Haitian counterparts, the events I described were often too common place. After all, violence (either in the home or in streets) is rampant in Haiti. For them, I wasn’t writing about anything fresh. The members of the writing group were kind but generally unimpressed, until my stories became more character-driven.

I once met a Caribbean writer at a Books & Books reading in Coral Gables. He trivialized my pain. “I see your father was a raging nightmare. What’s the big deal? I know you want to sell your book—and your American audience will be all over this story of a difficult upbringing. But I don’t believe for one second that you’re as broken as you pretend to be. We, Caribbeans, are thick-skinned. You’re sensationalizing.” But I wasn’t sensationalizing. In a TedX presentation, Nigerian writer Chimamanda Adichie says that she “learned, some years ago, that writers were expected to have had really unhappy childhoods to be successful.” Some writers play into that game. I don’t. I wasn’t using my pain to further my career. I was telling my truth, and no one was going to take that right away from me. I worked even harder on making my story unique by putting on the page characters that were gripping in their multi-dimensionality and by exploring universal questions about the limits of love and loyalty.

Sharing my work with different groups of writers-turned-critics allowed me to accurately gauge the impact of the book every step of the way. I learned to see Haiti from different perspectives, with everything that makes her unique and unforgettable, and I fell in love with my birth country all over again.

ORIGINS

You’ve also said “Haiti remains [your] primary source of inspiration.” Why does Haiti inspire your creative work?

FIÈVRE

Although I left Haiti 12 years ago, I never really “left.” I visit three or four times a year. I’m still connected: I follow Haitian politics via Haitian radio stations; I know about art and literary events; I read reviews of stand-up comedy shows. Sometimes, when I wake up in the morning, I want to drive to Kenscoff or Furcy and eat some griot. It takes me a while to remember that I’d need to cross an ocean. I carry Haiti with me and I’m certainly not trying to break away, so I continue to be inspired. My stories are character-driven; it couldn’t be otherwise because everyone in Haiti is a character. I’ve never met a boring Haitian. When I visit, I get at least 20 story ideas a day. These stories compete in my head. I’m working on a collection of flash fiction pieces—my favorite genre because there are some many stories to tell and so little time.

ORIGINS

You’re also incredibly adept at switching, mixing, and subverting genres. You’ve written children’s books, plays, mystery and horror novels, poetry, and short stories. Is there a genre you enjoy writing the most? Is there a genre you find particularly challenging?

FIÈVRE

I enjoy writing flash fiction the most. I’m working on a collection of twisted stories (in French) which, I hope, will blur the lines between insanity and normalcy. I find writing itself very challenging. I only became a writer because it was one of the few things I was somewhat good at. I was an awkward kid, so I held on to the first thing that would draw the attention away from my flaws. I’m a hard-ass editor, and by my own standards most of my writing is pretty awful. Whenever someone does appreciate my work, I’m genuinely thankful. You would think that after 20 years compliments get old, but they don’t. I feel like a fraud every day. There are moments when I find myself still waiting for my real calling. Then I realize I’m 34, and writing probably is it.

ORIGINS

Among your many other projects, you’re a publisher at Lominy Books, the founding editor of the popular magazine Sliver of Stone and you have edited three anthologies. How has your experience in the publishing world informed your writing?

FIÈVRE

Working on Sliver of Stone has taught me to come to terms with rejection letters. Sometimes editors can’t seem to agree on publishing a particular piece. It’s all very subjective. A piece can have a very gripping voice, an elaborate plot, and yet something manages to irk one reader during the final stage of selection. Then that’s it: a rejection letter is sent. I understand that now when I submit my own writing: I don’t (or at least try not to) take it personally. I’ve learned to ask at least three people to comment on my work before I send it out, no matter how great I might think the piece. People whose opinion I trust, writers whose work I admire. I’ve learned to appreciate the feedback from non-writers because I don’t want to only be a “writer's writer.” I’ve also learned to read a magazine cover to cover before I submit, so that I can be sure we’re a good match. I’ve learned to be thankful whenever a piece gets accepted because the odds are so great. So many writers out there!

Working for Lominy Books made me realize how much work is involved in putting out a book and how being a professional, as a writer, goes a long way. I’ve learned to appreciate even more the importance of grammar, punctuation, and fresh ideas. I’ve learned that editors are fallible beings: they miss errors. Writers shouldn’t rely excessively on somebody else to fix all of their mistakes.

ORIGINS

On your blog and in your literary journal Sliver of Stone, you’ve gone out of your way to highlight well-known and up-and-coming Caribbean writers. How do you feel about the representation of Caribbean writers in contemporary literature? Do you feel the conditions have improved for Caribbean writers?

FIÈVRE

I get so excited whenever I peruse the list of contributors to a journal and find a Caribbean author. The other day I was on The Nervous Breakdown and discovered André Alexis, from Trinidad. I read his work, Googled him, looked for ways to stalk him online. I actively seek Caribbean literature. I follow the Caribbean Writer on Facebook and I’ve created bookmarks leading to Wasafiri and Calabash, so that updates are one-click away. It used to be that in order to “read Caribbean,” you had to visit specialized magazines such as The Caribbean Review of Books (Trinidad), Anthurium: A Caribbean Studies Journal (University of Miami), and BIM Magazine (out of Barbados). Now Caribbean writers are everywhere, although I believe we could still be better represented in contemporary literature. Journals that specialize in art and literature that engage with issues of identity politics (such as Apogee Journal, Kweli Journal, Kinfolks Quarterly, and Callaloo) tend to feature more Caribbean writers than “mainstream” magazines.

Born in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, M.J. Fièvre published her first mystery novel, Le Feu de la Vengeance, at the age of sixteen. At nineteen, she signed her first book contract with Hachette-Deschamps, in Haiti, for the publication of a Young Adult book titled La Statuette Maléfique. Since then, M.J. has authored nine books in French. Two years ago, One Moore Book released M.J.’s children’s book, I Am Riding, written in three languages: English, French, and Haitian Creole. A Sky the Color of Chaos is her first book in English.

M.J. holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Education from Barry University and an MFA from the Creative Writing program at Florida International University. She taught writing at Nova Middle School in Davie, FL, and is currently a professor at Miami Dade College.