Achy Obejas: In Deeper Waters

An Interview by Lisa Page

Achy Obejas wears many hats. She is the author of the critically-acclaimed novels Ruins and Days of Awe. Her work explores contemporary Cuba, the Jews of Havana, the conversos of Spain, immigration, and queer life in the U.S. Her finesse with language is unique. She has translated into Spanish Junot Diaz’s The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao/La breve y maravillosa vida de Oscar Wao and This is How You Lose Her/Asi es como la pierdes. She also teaches writing and is currently Distinguished Visiting Writer at Mills College in Oakland, California. She’s one of the founders of the creative writing program at the University of Chicago. Obejas worked as a reporter before making the leap to fiction writing and remains on the editorial board of In These Times.

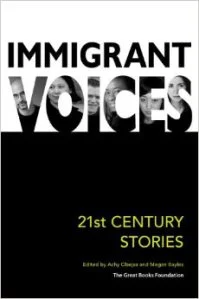

Her latest book is Immigrant Voices: 21st Century Stories, co-edited with her wife, Megan Bayles. The anthology is a collection of short fiction by Daniel Alarcon, Edwidge Danticat, Aleksander Hemon, Junot Diaz, Porochista Khakpour and others. The anthology is divided into three sections: Coming Over, Being Here, Going Back. She and Bayles wanted to present contemporary stories of immigration. They argue that last century immigrant literature is about becoming American, with displacement and exile as dominant themes. For many of these writers, like Maxine Hong Kingston and Isaac Bashevis Singer, there was no going back home. Today, Obejas and Bayles argue, “writers, and many of the characters they create, see themselves as transnational, bicultural, diasporic, global. Many of them embrace, rather than struggle with, their outsider status, and they define themselves as Americans with varying degrees of fluidity and comfort.” Here is an excerpt of her interview in the first issue of Origins.

ORIGINS

You worked as a journalist for many years before turning to fiction and you are still a working journalist. How do the two different forms of writing complement each other? How do they get in the way of each other? How do you prepare for one versus the other?

OBEJAS

I do a lot less journalism these days, and nearly all of it is commentary, and I'm pretty comfortable with that. I think, for me, journalism was a real blessing in teaching me how to research and organize, how to write clearly and concisely. But it's also been a curse at times. Journalism, because of the time pressure, teaches the writer a slew of tricks for filling or disguising holes in the story. And some- times, when you are so frustrated because the muse has refusedto alight, it's really easy to fall back on those tricks. And what that means is that the next day when you read over what you've written, you can't help but be angry at yourself for wasting time like that.

ORIGINS

As a translator, you are also a cultural ambassador, to a certain extent. How has this enriched your experience as a writer?

OBEJAS

Immensely, I think. It is the closest close reading experience I've ever had. And it makes me reconsider word choice and intent in new ways. I think it's made me a much more careful and precise writer. I also really appreciate a clean sentence in a way I never did before. There's no more arduous a task than having to translate a sloppy sentence in the original text.

ORIGINS

Your latest book is Immigrant Voices: 21st Century Stories, co-edited with your wife, Megan Bayles. You talk about a new kind of immigrant writing where immigrants embrace their outsider status. Would you elaborate on this and how it differs from 20th Century American immigrant writing?

OBEJAS

I think 20th century immigration to the U.S. was marked by two important things: one was the idea that the journey was final. Most people never imagined returning to their home countries, not even to visit, because the distances were great and the costs prohibitive. Moreover, the longer they stayed, the more severed the connection. The other thing was that many immigrants came with the idea of becoming Americans. A lot of folks voluntarily gave up their language and culture once here. But things are different in the 21st century: Travel is easier, quicker and cheaper, so people come and go. Moreover, technology allows a continued intimacy with the home country, whether it's Skyping with relatives or reading the local news in real time. This changes the relationship to the U.S. because it allows you to have a concurrent life somewhere else. And it means you're either more or less than American, depending, I suppose, on who you are and your particular circumstances, but not necessarily just American.

ORIGINS

Immigrant Voices features short fiction, as opposed to fact-based essays about immigration. Please talk about this choice. Would you also talk about the intersection of fiction and history?

OBEJAS

I'm always interested in the truth in fiction, and how fiction can dare go places so-called historical accounts can't. Part of the reason for that is that fiction is personal—the reader needs someone to identify with—and so the stories are always more intimate, smaller in dimension, and more accessible than the kinds of movements and forces that formal history contends with. I don't think Megan and I even discussed the possibility of a nonfiction anthology. The idea sprung from reading so much immigrant fiction—stories by and/or about immigrants—and what we began to identify as different elements from more traditional, i.e., 20th century literature about immigration.

I love history—I still think sometimes about going back to school for a Ph.D in history—but I'm more interested in actually provoking people's curiosity, in getting them to consider scenarios they hadn't imagined, than in actually presenting anything as an actual history. History depends a whole lot on point of view. I always tell my students about the Spanish-American War, how U.S. history books depict it as essentially a battle between the U.S. and Spain and pretty much leave Cuba out other than setting, eliminating Cuba's hard fought struggle for independence and elevating the last minute U.S. intervention. That same war in Cuba is called the War of Independence from Spain, and the U.S. is and has always been depicted very differently than here: never as heroes, never as liberators, always as intruders and occupiers. But both of those takes—which aren't really reconcilable —are "history" depending on whether you're in Texas or in Santiago de Cuba.

ORIGINS

You've said you see Cuba "as a real place and as a kind of metaphor for power and powerlessness, for private and public identity." What do you mean?

OBEJAS

Cuba is a country with a lot of binaries, and one of them is the person you present in public and the other is the person you present in private. On the surface, this doesn't sound extraordinary, but in Cuba's case, it is, in part because of the extremes this can take. Say, a national figure, a poet, decorated by the Revolution who actually writes verses praising Fidel, but during state-ordered blackouts drunkenly screams about shitting on Fidel. Or a woman married to an army colonel who, knowing she's protected by that marriage, sets her radio to Radio Martí at night and aims it out the window for her neighbors to hear.

Everybody knows about this duality, and about the different roles we play. For example, everybody heard the poet, everybody knew who had the radio on. And that begets a kind of complicity: that the poet who praises Fidel is as sick of him as you are, and that the colonel's wife isn't buying the official line, because it also means the colonel might not be buying it either, or as much, or at the very least is open to appeal—which is vitally important in a collective society. Nobody turns in the poet or the colonel's wife for these flagrant violations hope that the poet and the colonel's wife, or the colonel, will look the other way.

ORIGINS

Talk about your own experience with Cuba and the U.S.? Your particular story was what I longed for, as I read Immigrant Voices. The way you divide the book in three parts was fascinating and made me think of you "coming over," "being here," "going back."

OBEJAS

My relationship with Cuba is very complicated. I left as a six-year- old during the early years of the Revolution, on a boat with 43 other people, including my immediate family. From that point on, Cuba became a powerful abstract—it was both a terrible place and a place where everything had once been near idyll. And the messages were very mixed. For example, during every Olympics, the men in my family inevitably rooted for the Cuban boxers and took great pride in their achievements, even as the individual boxers were denounced as communist dupes or pitied for their supposed subjugation to the dictatorship. So Cuba became a kind of Shangri-La, the depository of both dreams and fears.

As an adult, I had an opportunity to go back in the 80s, but when I shared the news with my parents, they were horrified and very hurt. That hurt was more than I could bear so I chose not to go then. It would be more than a decade before I broached the subject again. By then Cuba was like a siren call. Interestingly, though my parents were dismayed by my decision to go, they were resigned to it. Initially, I'd thought their objections were political, that they were afraid for me. Later, though I think both of those things were true, I also realized there was a more personal fear. All my life, I'd experienced Cuba through them. Now I would experience it for myself and, undoubtedly, that would bring some of their reality into question. Their authority on the subject, if you will, would pass to me—and that was huge.

After that first trip, and for many years, I actually had a very divided life between Chicago and Havana, often spending months at a time, in Havana. It was a great experience to reintegrate, to make a life in my home country, to establish myself there. There were many things I loved—and many people I love still—on the is- land. But, of course, a longer exposure also brought out the cracks, the absurdities, the injustices, the repression. I now find myself quite impatient, especially with American leftists who still defend the Cuban government with B.S. about the embargo or literacy or healthcare because it really also misses the larger picture of daily life for the average Cuban, who never gets a break and has been on a campaign of personal sacrifice since before the Revolution. A lot of my Cuban friends, including those in government, talk pretty openly (if privately) about how the Revolution is over, that this is just a transitional phase until the next thing, which is whatever happens after Fidel dies. Yes, Fidel, not Raul. So long as Fidel is still around, even Raul can't really make structural changes. And Cuba needs structural changes.

Consider that, for the whole of its existence after the European conquest, Cuba—in spite of its historic revolutionary, nationalist, and independence rhetoric—has always been dependent on someone else to survive. First Spain, then the U.S., then the U.S.S.R. and now Venezuela. That's just a crazy history and that dynamic has got to change. For me, Cuba is a great font of inspiration precisely because of all these tensions, its utopian aspirations, its very dystopian realities. For a long time I imagined myself living the end of my life in Cuba. Now I think it'll probably be in the U.S. I havea child and I'm not a great believer in Cuba's medical prowess (It's great for prevention but it sucks if you actually have something wrong with you.), and I'm a natural worrier, so there's that. Also, my spouse is American, and my kid's only living grandfather is part of a happy, functional couple in Iowa, the very heartland of the U.S., so I've shifted to more of an embrace of my American life.

ORIGINS

I'm also fascinated by your many identities, as Cuban American, as queer, as an artist, as an activist. You've seen many things change in your lifetime. What has been the most dramatic? And how has this impacted your writing? Have your various identities gotten in the way of each other? Or do they fit together as one?

OBEJAS

I think the time of most conflict with my many identities was probably when I first arrived in Chicago. I was in my early twenties and being pulled in a lot of different directions. The struggles in each community were very different and often seemed dismissive of the others. But I think a lot of bridges have been built since then, and things feel more integrated.

ORIGINS

You always seem to have embraced your own "outsider" status. What enabled you to do this?

OBEJAS

I don't know. It's funny because my mom is a total don't-rock-the- boat person. But my dad, who I think was also very much an out- sider in his way, was always supportive of me just being me. I mean, he was a tragic figure in a lot of ways, but that was in part because he had dreams that positioned him against the grain, and that was attractive to me. Or maybe, more precisely, I identified with it. I also think when you know you're queer from early on, you have a keen sense of difference. I knew as a child and I was comfortable with my attractions, so the question for me was about finding a way and a place to be me rather than trying to change. I just figured my journey was never going to be in the mainstream, but in deeper waters. And that was fine by me.

Read more of this interview in the Issue 1 of Origins.