An Interview by Dini Karasik

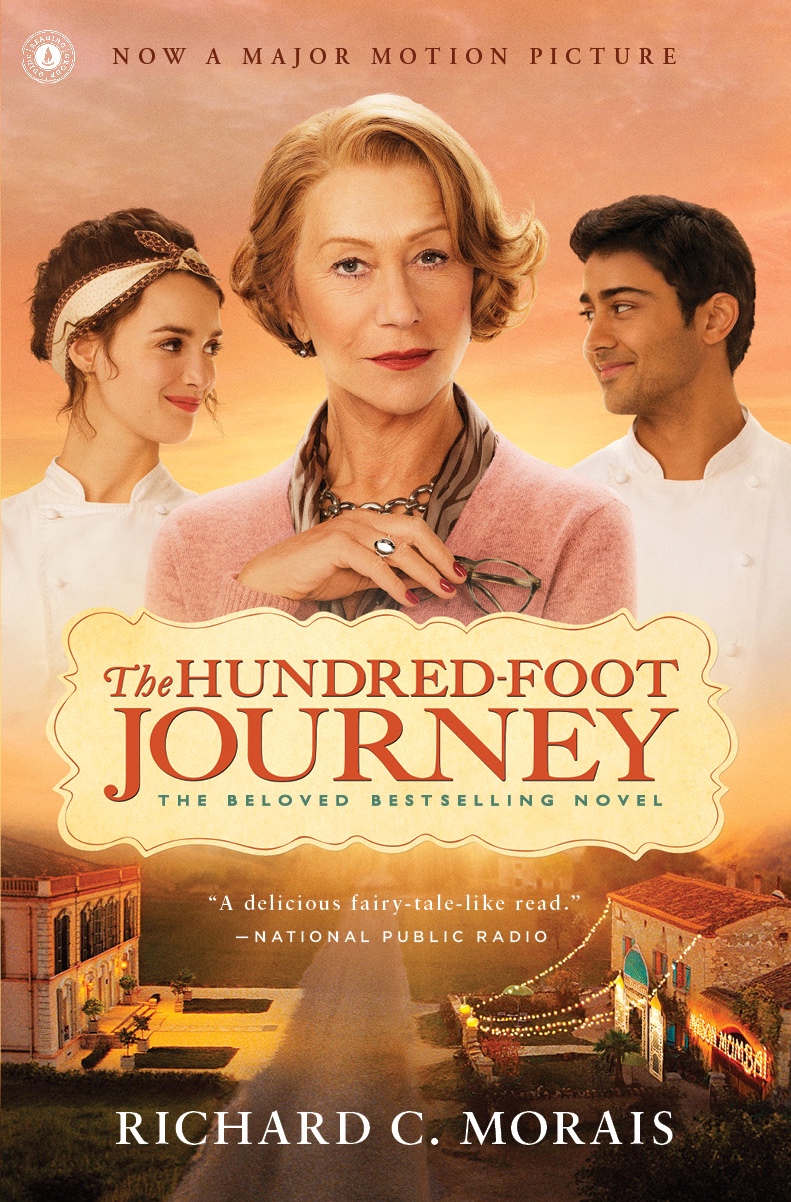

Richard C. Morais is the author of the international and New York Times bestseller, The Hundred-Foot Journey, which was recently made into a film by DreamWorks Studios and Harpo Films. A young chef is exiled from his native India but later becomes a three-star Michelin chef in France. It’s a story about family, food, and culture that asks deeper questions: What is identity? Is it inherited or adopted? What is “place” and how does it inform who we are?

Morais’ second novel, Buddhaland Brooklyn, follows a Japanese Buddhist priest who reluctantly travels to New York to establish a Buddhist temple. Identity is also a theme, particularly in the context of faith and personal transformation. These are subjects that matter to Morais. A Buddhist from the age of 19, he writes to answer questions and about who he is and where he belongs in the world.

Born and raised in Europe to an American mother and Canadian father of Portuguese descent, Morais arrived in the United States at the age of 16. This was a pivotal time for him, as he began his studies at Sarah Lawrence College, wrestled with his identity, and embarked on a prolific career as a writer. As a journalist, he has enjoyed success both as a foreign correspondent and as European Bureau Chief for Forbes. He is now Editor of Barron’s Penta and is at work on his third novel.

Recently, Globals Ties, U.S., a nonprofit partner of the U.S. State Department that supports and coordinates international exchange programs, awarded him their highest honor: Citizen Diplomat of the Year 2015.

Here is an excerpt of his interview from our first issue:

ORIGINS

In both of your books, the protagonists confront new cultures and people who are often their polar opposites. Is this another way to search for commonality?

MORAIS

Perhaps, but it is also about something more fundamental. Regarding the cultural clashes, I think there are people in this world who happen to be attached to the soil of their ancestors. Through my journalism, I have seen people—like economic refugees or war refugees—who were torn from their lands abruptly. It takes generations to work through that trauma.

This need to stay connected to home and place is primal. It’s sort of like Scarlett O’Hara in Gone with the Wind, who has to be attached to her family homestead, Tara, and the soil of her ancestors. There’s that moving final scene in Part I, where she clutches Tara’s earth and swears she will survive, and that earlier scene when her father warns Scarlett she has to be attached to Tara. Such people, if they are not attached to their land, become unstable.

Conversely, there’s another kind of person who has a calling in life that’s greater than family, greater than their immediate culture. They have to go out in the world to fulfill their mission in life. If you force them to stay at home, they will become unstable. You see a lot of young people, in the American hinterlands or in a town in the midwest somewhere, where they have very little prospects and they join the military to get out of town. They have to go out into the world to find their true calling in life.

All of my books tend to be about the latter kind of person and in Buddhaland Brooklyn, Reverend Oda thinks he’s the type who needs to stay attached to his birthplace, but it turns out he doesn’t.

ORIGINS

It’s true. In Buddhaland Brooklyn, Reverend Oda thinks his personal salvation is in his monastery in Japan but he only “saves” himself when he plants roots in a totally new place. His journey speaks to the ability of human beings to survive, to acclimate, but also to the ways in which the world is so small. Is it better to be attached to one’s homeland or to leave it behind in search of one’s “true calling?”

MORAIS

Both have their pluses and minuses. There is great sense of security in knowing where you’re from and where your ancestors are from. It gives you a basis, a foundation, that is very valuable in terms of processing the traumas and vagaries of life. But it’s also very limiting. Sometimes the soul has a greater calling than that. People are born with these innate drives which are sometimes in direct conflict with their family and culture. Then it becomes a negative and they have to address what compels them to be restless and unhappy in their hometown.

A friend of mine once told me, “You know, Richard you are writing about the international soul.” Using that term as shorthand for a second, international souls have to travel, to cross cultures, to find their place in the world. It is the way they are liberated from the tyranny of expectations and cultural rigidities and practices that tend to hold people back. They get liberated that way but then lose their moorings, to some degree, and then they have to create new moorings. And the trouble with international souls is that we become residents but never true citizens of any country. Real citizenship requires a committed, deep, I-will-spill-my-blood-for-this-soil kind of sensibility which gets eroded because the more you travel and live in different places, the more you see. You come to realize there are many different perspectives in the world and you become less rigid about the one perspective you inherited when you were born.

ORIGINS

The Hundred-Foot Journey is about food, family, nostalgia and Buddhaland Brooklyn is about faith; these are the very things that tie us to country and culture. But in both books, you also raise serious philosophical questions about mental illness, loneliness, and loss. Is writing a way to overcome your own struggles? Is it also a kind of advocacy?

MORAIS

Advocacy…maybe. Honestly, writers are so narcissistic. I’m writing for myself. That’s how I was able to write fiction for almost 20 years without any positive feedback. Finally, I hit a tipping point and had some commercial success. But I couldn’t even get published for 18 years. You can only do that—writing, banging your head against the wall when no one wants to listen to you—if you get some deep satisfaction out of it.

I love to write. I love to armchair travel. But as you suggested, it is how I work through the problems of life. I’m so amazed by how often I am writing about something and then it happens in the near future. Right now, my father is in his mid-eighties and deteriorating, particularly mentally, and I’m writing a new book about a Spanish banker who’s at the end of his life and taking stock. He has brain tumors and illness affects his ability to process things. It’s got brothers in it. This weekend, I had all my brothers here to visit. We went up to my parents’ house to discuss what to do about our parents at this stage in their lives. It’s just amazing to me. This is stuff that I’ve been working out on paper for the last two years and, sure enough, it’s happening now.

ORIGINS

Can you talk about the idea of impermanence in life and in writing?

MORAIS

Well, as you know, one of the central tenets of Buddhism is the idea that illusion is a source of suffering. And I would say impermanence is the true state. Things that you think are permanent create the illusion and the suffering. Everything is in flux constantly and there is nothing you can take for granted. I’ve been happily married for 31 years but if you ask my wife, she’d probably say, “We struggle to stay married every day of our lives.”

I worked for Forbes for 25 years and at the fourth round of layoffs, I was laid off. I got a severance package that allowed me to finish the second novel. So, it worked out. But things end. Nothing stays the same. And yet there’s something about the human experience that makes us try to keep the whole world from falling apart. That’s also one of the lovely things about human beings: we are constantly trying to hold it all together. But the fact is that we can’t always. We can manage things for a little while but eventually they fall apart.

I’ve been a Buddhist since I was 19 and I say prayers everyday. Buddhaland Brooklyn was about trying to work through my own faith, how that has gone through a transformation over the last 30 years. But it’s also about karma and the idea that there’s a continuum and that everything that we do and think leaves a karmic impression. Everything that we experience is a summation of that. In the Buddhism that I was taught, enlightenment is contained in the very effort to become enlightened.

The rhythm of being a Buddhist and praying everyday is also the rhythm of writing. I write everyday. If I don't write fiction every day because my day job and journalism gets too demanding, I feel it. I’m edgy, anxious, unhappy. I’m not returning to my deepest state. And both writing and Buddhism do that for me. I’m kind of a cheery, upbeat guy until I don't do those things that get me back to my core being and get me back in touch with what is truly important.